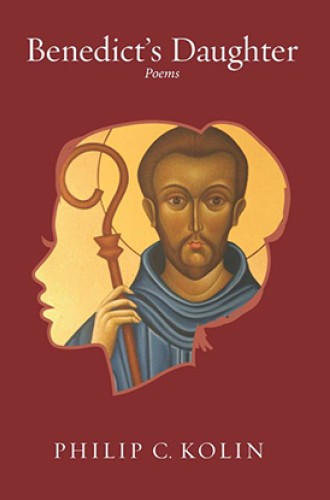

Poems in honor of a Benedictine life

Philip Kolin's longtime spiritual director was a chain-smoking oblate who fed everyone.

Philip Kolin’s eighth collection of poems is arguably his best. Resonating with a deep spiritual beauty that comforts, the poems reveal not only the world of the Benedictines but also an extraordinary woman—Midge Parish, an oblate who served the poor and disenfranchised for 40 years, living what might otherwise seem an unremarkable life. The collection also reveals a poet who has carefully stitched his poems together into something like a sacred scroll.

Over the past 40 years, Kolin has managed to tally an impressive bibliographic scroll as well. His childhood in Chicago in the 1950s and subsequent decades of teaching at the University of Southern Mississippi led to his preoccupation with another Chicagoan, who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955. Kolin’s 2015 book, Emmett Till in Different States: Poems, reflects his commitment to addressing the evils of racism. He has also written extensively on Shakespeare and Tennessee Williams, served as editor of the Southern Quarterly, and published over 40 books and 200 articles on modern American drama, with a focus on African American drama.

Benedict’s Daughter captures something of the evanescent inner life of St. Benedict, or what Abbot Cletus Meagher recognizes as the “monk within” many of us, not only in Midge Parish but in Kolin as well.

Parish was Kolin’s spiritual director for more than three decades. Sixty years ago Parish applied to the Benedictine Sisters at Sacred Heart Monastery in Cullman, Alabama, but was rejected because of ill health. Not to be curtailed, she turned instead to St. Bernard Abbey, where she made her vow of stability. In time, she and her husband Al became oblates there, and she found her vocation in teaching generations of schoolchildren. In addition, she provided spiritual counseling for so many that she became known as the “Prayer Lady.” She had a keen sense of humor, smoked one cigarette after another, and cooked and baked for the hungry who came to her house constantly, keeping three freezers full of food on her back porch to feed them. Besides her three biological children, she had at least ten spiritual children, Kolin among them.

With her death, it is left to Kolin to scatter his prayers across the pages of the Manual for Oblates that Parish bequeathed to him.

I have learned that prayers

are not meant to be read

as much as to be inhaled,

each opening, each page

a thurifer, . . .

The clarity and crispness of lines like these reveal a deep spiritual authority. In poem after poem, we hear revelation mixed with a surrealism that echoes such southern writers as William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and James Dickey.

In the opening of “Guardian Dogs,” for example, angels take the form of Midge’s dogs:

St. Roch or Don Bosco did not love dogs

as much as you did; angels without wings,they nestled next to you. Fierce prophets

let loose from caves to warn you aboutthe malice and snares of anyone

who rang your doorbell, unlatcheda door, dared to enter, if only to hug you.

They would have rushed the gatesof hell to pursue your enemies,

chasing them with fury deeperand deeper into Sheol’s pit. They leapt

straight out of Revelation.No wonder their names began

with End Time letters—Xena, Yowl, Zap.

There’s St. Roch, the patron saint of dogs. And Don Bosco, who dreamed of a woman who showed young Bosco that the same bullies who had attacked him like snarling dogs were, under their own fears and uncertainties, gamboling lambs, something which led Bosco to make work with lost boys his life’s work.

And then there are the dogs themselves: those guardian angels without wings who watch over Parish, fierce prophets watching for the “malice and snares” of the devil (a phrase lifted from the Catholic prayer to St. Michael), racing on all four paws to the front door as it rings to let any would-be intruder straight into the pits of Sheol. Even their names, beginning with the final letters—X, Y, and Z—embody the end time. There’s Xena, manifesting a hatred of the dark unknown. And Yowl, signaling a loud cry of pain. And Zap, which would eliminate any perceived or real threat the way fierce watchdogs do—or the way Dante’s comic thug-like devils do along the pits of the Inferno.

On the other hand, there is a poem like “Compline,” the prayer observed each evening for centuries by monastics. Parish too observes the ancient hour in her home on 33rd Street, as darkness descends and the nuns “entreat angels to make rounds / evicting sin-sated whisperers / and phantoms in harlequin disguise,” those involuntary, nagging fantasies that disturb our rest. But instead of churning over the day’s evils, these women have learned to place themselves in God’s hands, settling into sleep under a “shelter of feathers and wings.” Now it is the convent which “has silenced the sky— / no bell clangs or calls / in this dark season; the day is done.” If Kolin has managed to capture an authentic sense of the enclosed garden, the hortus conclusus, it is because each word he offers has been stripped to its sacred essence.

In these poems Kolin, a poetic master, offers many gifts: humor, a first-rate anagogical imagination, and an abiding sense of the sacred within the everyday (which one can capture only by having lived it for a long time in prayer).