James Baldwin's tough love for America

Baldwin’s words in Raoul Peck’s film indict us, but they also help us envision a new future.

I walked up to the ticket counter at the AMC theater in Denver and said to the young—maybe Latino—cashier, “I Am Not Your Negro.” He looked at me and raised his eyebrows. “What?” he said. There was a pause. I was flustered. I wasn’t sure if I should repeat myself. “Um . . .” he finally said. “We don’t have that one.”

I went back to my smartphone and found another theater just five minutes away with a showing. At this theater, the woman in front of me in line, a young black woman with an elegant headscarf, handled the question with more grace than I had. She said, “One for the James Baldwin film.”

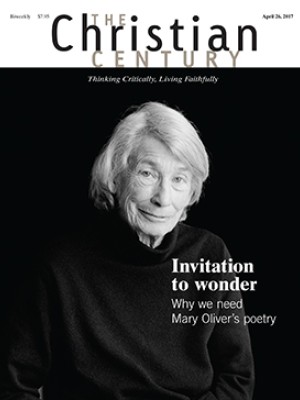

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

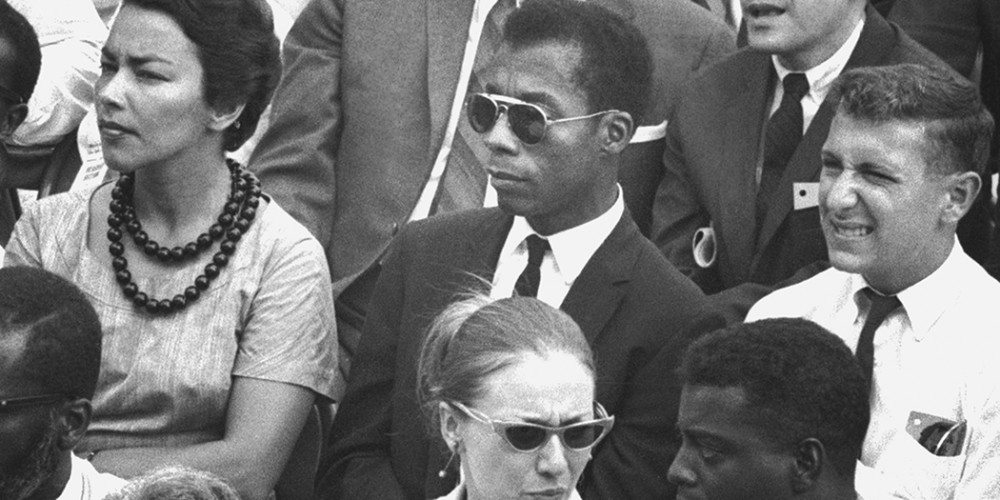

The James Baldwin film, I Am Not Your Negro, is a documentary by Raoul Peck that takes the words of James Baldwin’s unfinished final manuscript Remember This House and transforms them into a contemporary meditation on race, culture, and politics in America. The words of the film are almost entirely Baldwin’s, read by Samuel Jackson, mixed with clips from interviews with Baldwin and other figures from the civil rights movement. The film moves back and forth between historical and contemporary footage, reminding the viewer continually that this is not a piece of documentary history but commentary on the present moment. There are images from Ferguson and Times Square and photos of all the unarmed black men killed by police in 2014 and 2015.

As history becomes commentary and moves back again to history, one funny and ironic if painful sequence has footage of the Obamas juxtaposed with comments by Bobby Kennedy from the early 1960s. Kennedy says, “There is no question about it. In the next 40 years a Negro can achieve the same position that my brother has. . . . We have tried to make progress and we are making progress.” To which Baldwin scathingly replies, “From the point of view of the man in the Harlem barbershop, Bobby Kennedy only got here yesterday—and now he’s already on his way to the presidency. We’ve been here for 400 years, and now he tells us that maybe in 40 years, if you’re good, we may let you become president.”

For Baldwin, African-American experience is American experience. “The story of the Negro in this country is the story of America, and it is not a pretty story.” The film shows the young Baldwin eager to flee from his country’s story. He lives in France and tries to gain some perspective on where he came from, its terrible violence, its deep hatred for his very existence. But as the civil rights movement heats up, he realizes that he cannot stay apart from that story. It calls him home.

Again and again Peck depicts Baldwin, a cigarette smoldering between his fingers, sitting next to a white television show host—often it is Dick Cavett’s all too innocent, boyish white face next to Baldwin’s intense, vivid visage—telling the white man what he seems to be unable to recognize. “What is going to happen to this country?” he asks Cavett rhetorically. “All your buried corpses are starting to speak.”

The film explores white “innocence” predominantly through screens: television, movies, and advertising. In Nobody Knows My Name, Baldwin writes, “I am afraid that most of the white people I have ever known impressed me as being in the grip of a weird nostalgia, dreaming of a vanished state of security and order against which dream, unfailingly and unconsciously, they tested and very often lost their lives.” He diagnoses what he calls “the emotional poverty of whites”—their glaring inability to face reality, their preference to imagine themselves as Gary Cooper and Doris Day instead of the “moral monsters” that the civil rights movement revealed them to be. He points to the “guilty and constricted white imagination,” “the failure of whites’ private life,” that he saw exemplified in the escapist culture of television.

One of the most deeply rooted racial problems Baldwin identifies is a linguistic one. In Baldwin’s understanding, “white” was created at the same moment as “black.” Both are fallacies that script an unending cycle of despair. In a debate with William F. Buckley, Baldwin says, “Until the moment comes when . . . we the American people are able to accept the fact . . . that on that continent we are trying to forge a new identity for which we need each other . . . there is scarcely any hope for the American dream.” For the sake of our children, Baldwin writes elsewhere, “one must be careful not to take refuge in any delusion—the value placed on the color of the skin is always and everywhere and forever a delusion.”

What challenges the illusion of white innocence is the street. Granted, street scenes are also images that appear on screen: most white Americans experienced the civil rights movement, and now Black Lives Matter, through their television or computer screens. But these screens reveal a more menacing reality than Hollywood’s depictions: the street is where black people fall victim time and again to well-armed, uniformed white men. They are beaten; they are shackled; they are shot.

In his lifetime, Baldwin was a controversial figure who did not fit well into any of the movements of his day. He resisted Black Power and Black Muslims. He was not in an easy alliance with King, Evans, or Malcolm X. Baldwin describes himself as “the most despised child of this house,” even while he resisted the labels “black,” “Negro,” “homosexual.” “I was never in town to stay,” he says in I Am Not Your Negro.

Nevertheless, the one group to which he did actually claim to belong was America itself. Fraught as American life was, he claimed to be flesh of America’s flesh and bone of its bone, a child of this continent. He constantly questioned America’s future in a way that suggested his deep identification with it. While white America might imagine Baldwin as “the other,” he never accepted this distinction. He was a human being first and an American second—all other distinctions were lies that gave a false structure to the world. “I love America more than any other country in the world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually,” he writes in the “Autobiographical Note” to Notes of a Native Son.

In I Am Not Your Negro, Peck returns wordlessly and repeatedly to visual images of the sky. The camera lingers on sunsets and sunrises viewed from a vehicle moving along an American highway. These might be either hopeful or ominous images. The sun might be rising on a new day for America or setting on the American experiment. They offer relief in the midst of a film thick with the grainy footage of police beatings and shootings. The road and the sky have functioned in American mythology as offering the possibility of both escape and reinvention. We may be unable to give an honest account of our history or we may yet become the America that Baldwin imagined for us. But, Baldwin reminds us, “nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

A version of this article appears in the April 26 print edition under the title “Language in black and white.”