I’m deeply ambivalent about my speaking voice. On the one hand, my voice is a small miracle. Vocalizing requires an incredibly broad range of activities, including muscles, nerves, and the brain. It requires all of the senses, even touch. Indeed, lacking touch, a voice cannot form recognizable sounds particularly well (something those of us who have experienced a shot of Novocain at the dentist can recall).

On the other hand, I wish my voice sounded more like the rich baritone of Morgan Freeman’s, and not so much like the nasal, middle-register voice that I have—a voice I suspect is more effective at communicating with furry creatures than with my fellow humans.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

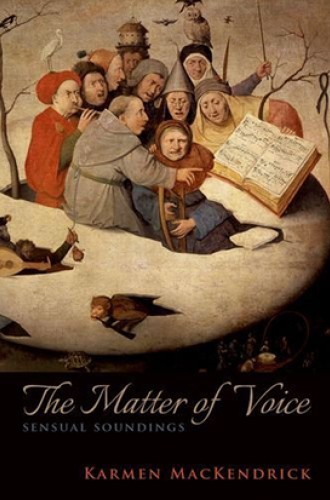

This ambivalence is not mine alone. It is a theme that in part undergirds Karmen MacKendrick’s book. She meditates on the sensuality of the human voice, both spoken and written. The voice is largely ignored in philosophical thought, shoved aside in the search for objectivity; MacKendrick plays with the idea that the “voice is what resists the reduction of word to concept.” The human voice is reducible neither to mere body nor to mere thought; rather, it fully participates in the act of making meaning. A voice is one’s own, but not identical with the self (hence the foreignness of hearing a recording of one’s voice). It is a physical, bodily trait, but it requires mental and spiritual capabilities. In its most basic form, a voice erupts outward, affecting others, calling forth a response. It both calls and responds, both speaks and listens, always a partner in searching for God.

A professor of philosophy at Le Moyne College, MacKendrick has written a book that twists and turns in conversation with figures like Augustine, Hildegard of Bingen, Nietzsche, Jean-Luc Nancy, and Jacques Derrida. She critiques the view that the voice is merely a delivery device for ideas. Rather, as relational, the voice intertwines with words and a listener. It makes meaning because within it is the power of breath, part divine and part human. As God gives us breath, in using our voice we mingle the divine with the world. Doing so also rests upon the mythic notion of an original language, one that harkens back to Genesis and a God who gives us the language to voice our desires and thoughts. The voice, through tone, silence, and song, is more than a means for the transmission of words. The voice frames our experience of the world as meaningful because it allows our bodies to participate, interpret, form, and re-form the materiality of the world as full of divine presence.

MacKendrick stresses the human distance from and inability to possess the divine—an awareness that opens up a space for multiple ways of doing theology. This view then creates an opening to recognize that our desire to vocalize the mystery of divinity pulls us into multiple ways of relating to God. She threads this view into several different human activities that require thoughtfulness about voice: writing, pedagogy, translation, cosmology, semiotics, and music.

The book’s constructive proposal stresses that voices allow our bodies to become the locus for meaningful conversations about God. These events arise through our speaking, writing, teaching, and singing, among other acts, with each voice echoing out to call others (as well as respond to others) in an exploration of divinity. Such meaning making is particularly heightened when we sing. In singing we emotively experience the vocalization of the intimate mystery of divine presence without being entangled in a quest for certainty and clarity.

At times, MacKendrick’s voice is overly clever, too stylistic and rhythmic rather than focused on clearly articulating her argument. And the arc of the book, based on five previously published essays, feels disjointed (especially in comparison to the elegance of her Divine Enticement). But the thread that knits the text together is valuable: she calls us to care about the movement of our voices, the multiple ways we use them, and the embodied conversations that burst forth as we live out our desire for God.

MacKendrick asks us to appreciate the rhythm that each voice taps out and the multiple ways these rhythms draw us together as voices, desires, and bodies. She reminds us of the wonder of creation and of having a sensual voice in the first place. In the midst of our ambivalence about our voices, this book calls us to be joyful in our corporeality, ever aware that our voices matter.