Christ in all that is

All living things are touched by divine grace—and caught up together in movement toward union with God.

A rich tradition of literary and visual art—think of the lyrical poetry of the English Romantics, the writing of the American Transcendentalists, or the landscape paintings of the French Impressionists—bespeaks a vision of nature as “charged,” in the words of Gerard Manley Hopkins, “with the grandeur of God.” In his 2001 Dialog article “The Cross of Christ in an Evolutionary World,” Danish theologian Niels Gregersen introduces the concept of “deep incarnation” to give theological expression to this perception, common to poets and artists, of a God who is present everywhere throughout the created universe. God’s incarnation in Christ reaches into the heart of material, biological, and social existence and even affects what Gregersen nebulously refers to as “the darker sides of creation.” Gregersen offers this technical definition of deep incarnation:

the view that God’s own Logos (Wisdom and Word) was made flesh in Jesus the Christ in such a comprehensive manner that God, by assuming the particular life story of Jesus the Jew from Nazareth, also conjoined the material conditions of creaturely existence (“all flesh”), shared and ennobled the fate of all biological life forms (“grass” and “lilies”), and experienced the pains of sensitive creatures (“sparrows” and “foxes”) from within.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

While God is uniquely incarnate in Jesus, that incarnation extends into the depths of the created world in such a way that all living things are touched by divine grace and are caught up together in movement toward union with God.

Some modern theologians speak loosely of God’s presence in the world as a kind of generalized incarnation and a few, most notably Grace Jantzen and Sallie McFague, conceive of the world itself as “the body of God.” The traditional understanding of the incarnation, however, at least as it is expressed in the Chalcedonian Creed, is the union of divinity with the specific humanity of Christ. Gregersen calls this formulation the “strict-sense view” of the incarnation and contrasts it with a “full-scope view.” The latter view accepts the classical account of Christ’s two natures but enlarges upon it so that Christ’s risen body is seen to encompass not only the church but also the rest of humanity and all life forms on earth. Gregersen does not conclude, as do Jantzen and McFague, that God is embodied in the whole world but rather that God, through the incarnate Christ, is present “for” and “with” all creatures and, in that limited sense, is “in all that is.”

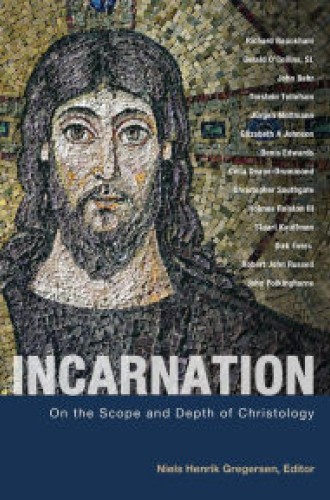

Incarnation contains essays by prominent European and American theologians, philosophers, and scientists responding to the challenges raised by Gregersen’s expanded account of Christ’s incarnation for our understanding of God and the natural world. Gregersen edited the book and wrote its introduction as well as two of its chapters, a programmatic essay on deep incarnation and a reply to the arguments put forward by his fellow authors. The book contains three sections: the first mining New Testament and early church sources for a theology of deep incarnation, the second offering reflections by systematic theologians including Jürgen Moltmann, Elizabeth Johnson, Denis Edwards, and Celia Deane-Drummond, and the third exploring the issue of deep incarnation in light of contemporary philosophy and science.

The principal touchstones in scripture for the concept of deep incarnation are the opening verses of the Gospel of John and its affirmation of the Word (the Greek logos) made flesh, depictions of divine Wisdom (sophia) in the Old Testament and Deuterocanonical literature, and the portrayal of the cosmic Christ in the writings of Paul. As a number of contributors emphasize, John never says that the Word becomes human but rather that the Word becomes flesh. In the Bible, the flesh (basar in Hebrew and sarx in Greek) can refer alternatively to the human body, the whole human person, body and soul, the whole human race, and living things in general (as in Isaiah’s declaration that “all flesh is grass”). It can therefore be reasonably argued that, in Christ, the Word became flesh and dwelt among all fleshly life. Both the Word and Wisdom in scripture are identified with the incarnate Christ and are means of conceiving of God’s creative, providential, and saving activity in the world.

For several authors in the volume, however, the figure of Wisdom provides a more thoroughly personal, ethically and practically oriented, and evocatively feminine image of Christ than the abstractly conceived logos. Paul’s confession of Christ as the One who is “before all things” and in whom “all things hold together,” and who is reconciling all things to himself (Col. 1:17, 20) also lends support to the full-scope view of the incarnation as the beginning of a process through which all creation will be taken up into the life of God. Finally, the writings of Athanasius and Maximus the Confessor present accounts of the incarnation of the Word that highlight its transformative effects on the wider creation.

The concept of deep incarnation is rooted in the classical Christian tradition, but it also speaks to contemporary evolutionary and ecological worldviews. In the modern story of cosmic and biological evolution, as Elizabeth Johnson observes, “Everything is connected with everything else; nothing is isolated.” When the Word assumes the flesh of a human being, it becomes the member of a single biotic community, the deeply interconnected, evolutionary family of life, embracing all the regions of the globe and vast spans of the earth’s history. Defenders of Christian stewardship of the environment typically appeal to the goodness and integrity of the created world through an ecologically minded reading of the first few chapters of Genesis, but the essays in this volume are a reminder that the church’s theologies of incarnation and salvation are as important as its theology of creation for promoting respect and care for life on the planet. Everything we do to heal or harm the environment simultaneously builds up or tears apart the emerging body of Christ in the world.

Not all of the contributors to this book, however, are persuaded by Gregersen’s robust interpretation of Christ’s “divine stretch” into the furthest reaches of creation. John Polkinghorne worries that extending the concept of incarnation beyond the human person of Jesus blurs the distinction between the Creator and the creation. The transcendence of God is necessary, he argues, for incarnation to be intelligible and for there to be genuine hope for the world’s future. Thus he insists that God’s particular incarnation in Christ must be sharply distinguished from God’s general immanence in the world. God is incarnate as Jesus of Nazareth but is immanently present alongside the rest of the creatures in the world. Holmes Rolston objects that no scientifically verifiable evidence of the incarnation’s transformative effects can be discerned outside of humanity. The physical states of matter, and the biological forms of various nonhuman species, have shown no changes over the last 2,000 years that set them apart from the time before the advent of Christ. We cannot even imagine what a “redeemed quark” or “transfigured elephant” might be like, and so it is best to regard such eschatological notions as poetic expressions of “human hopes for redemption within culture.” Robert John Russell counters with an ingenious nonlinear model of time that opens it to the presence of eternity. The past is preserved through memory and the future is already partially realized through hope in the present moment. Time is therefore less like a straight arrow than a feather with a stem and barbs, the stem indicating a clocklike movement from the past to the future and the barbs pointing to moments in time that are pregnant with a future eschatological reality.

The theologically imaginative, philosophically sophisticated, and scientifically informed perspectives that make up this finely edited volume of essays do not present a unified front on the question of deep incarnation. But they invite further conversation about the meaning of the central event of the Christian faith and its implications for contemporary ecological concerns, inclusive views of salvation, and theological assessments of current scientific knowledge about the natural world. The vision of deep incarnation also entails a corresponding vision of the deep transfiguration of the world. While conversation with science and philosophy can provide us with a partial glimpse of how God’s incarnation in Christ transforms church and world, a richer trove of insights might be attained through a theological engagement with works of the literary and aesthetic imagination as well. Transfigured elephants are fictions in the minds of scientific naturalists, but not in the minds of religious artists. The writer who intuited God’s incarnate grandeur in the “dearest freshness deep down things” was, after all, a poet and not a scientist. It is in poetic visionaries like Gerard Manley Hopkins that we may find the most convincing evidence of the depths of God’s incarnation in Christ.