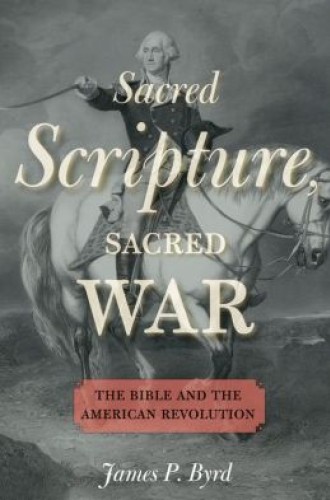

Sacred Scripture, Sacred War, by James P. Byrd

When a hurricane ravaged the waters off of eastern Newfoundland on September 9, 1775, churning waves up to 30 feet, the devastation was enormous. Four thousand sailors drowned, most of them from Ireland and England. The British Royal Navy lost two armed schooners. When word reached the American colonies, William Foster, a Presbyterian minister, eagerly fit what became known as the “Independence Hurricane” into an ancient and venerable typology. “Pharaoh’s chariots and his hosts were cast into the sea,” Foster preached to American soldiers; “they sank as lead in the mighty waters.”

The American Revolution was by no means the first time preachers wielded the Bible to justify armed conflict and the slaying of enemies; they did the same during the Crusades, of course, and the French wars of religion, not to mention the English Revolution, which culminated in regicide. In the American colonies, as James Byrd points out in this superb book, ministers used the scriptures to justify violence at least as far back as King Philip’s War in the 17th century.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Byrd makes a persuasive case for the centrality of sermons in propagating and justifying armed rebellion. “In the biblically saturated American colonies, ministers were the agreed-upon experts on the Bible,” he writes, and “their sermons were the most serious engagements between scripture and war in America, both before and during the Revolution.”

It is hardly a new observation that different groups of believers emphasize different parts of the Bible—Catholics and mainline Protestants, for example, prefer the Gospels, whereas evangelicals gravitate to the Pauline letters—but Byrd demonstrates that 18th-century preachers were remarkably nimble in their biblical interpretations. “In battles against the Indians and the French, and in the later Revolution against the British,” he writes, “wars influenced which biblical texts colonists saw as being most important and how they applied those texts in their political and spiritual lives.”

Byrd argues that the French and Indian War (the American iteration of the Seven Years’ War) provided a rhetorical warm-up for the American Revolution. Preachers decried the Boston Massacre of March 5, 1770, as a “horrid murder” that recalled Cain’s slaying of his brother, Abel. By the time of the Stamp Act, the Quebec Act and the Intolerable Acts, the sounding boards of pulpits were reverberating with righteous indignation toward the British. In 1772, for example, John Allen, a Baptist, preached An Oration, Upon the Beauties of Liberty, or the Essential Rights of Americans, which went through five editions and seven printings.

Underlying Byrd’s astute analysis is a database of biblical references he compiled. One of the most popular texts during the Revolution was Exodus 15:3: “The Lord is a man of war.” Indeed, the Exodus narrative figured prominently in Revolutionary era sermons. George Washington was viewed as Moses, and colonists, goaded by the preachers, increasingly understood themselves as the beleaguered Hebrews toiling under the scourge of slavery in Egypt. The Promised Land of liberty lay at the far end of the wilderness of Revolution.

Although John Wesley, Samuel Hopkins and more than a few black preachers pointed out the irony of white slaveholders identifying themselves as bond servants, the Exodus metaphor served as a powerful motivation for armed revolution. “By making the Exodus story their own,” Byrd writes, “the patriots set the parameters for later Americans, including nineteenth-century slaves, who saw the liberation of the Hebrews from Egypt as a model for their own struggles.”

Preachers frequently invoked the pugilism of the Song of Deborah and the curse from Jeremiah against those who refused to take up arms: “Cursed be he that keepeth back his sword from blood” (Jer. 48:10). Some preachers took gruesome delight in recounting Jael’s murder of Sisera, the captain of Jabin’s army: Jael took him into her tent and then, with a hammer, drove a spike through his skull. The lesson was clear: pacifism in the face of British tyranny was no option. In Byrd’s words, “To refuse to fight this tyrannical power was to reject both a civic responsibility and a sacred duty.”

David’s battle against Goliath also figured prominently in the rhetoric, both to justify violence and to embolden a militarily overmatched populace. Even the Continental Congress invoked David’s contest to build popular support for the Revolution. As for the epistles, they could cut both ways. Paul counseled obedience to authorities, but patriot preachers deftly deflected emphasis toward Paul’s letter to the Galatians, which, Byrd writes, “gushed with liberty—nearly unbounded liberty, liberty that was both civil and Christian.”

The surprise here—and Byrd is surprised as well—is that the book of Revelation was not invoked more frequently in Revolutionary-era sermons. The author explains this by positing that wartime ministers focused on “apocalyptic militancy, not on an American millennium.” Still, plenty of preachers found analogs for dragons, the mark of the beast, and the woman with a crown of 12 stars. In the hands of such preachers, “Revelation portrayed a military Jesus who corrected the mistaken image of a pacifist Jesus.”

Byrd concludes that for the Revolutionary generation, “the Bible was a dramatic, often graphically violent, succession of war stories featuring heroic exemplars of spiritual faith and military prowess.” But what about those who dissented, especially those associated with the peace churches, who faced persecution, vandalism and the distraint of goods for withholding their support for military action? This void in Byrd’s account is doubtless due to the nature of sources: although Quaker and Mennonite rhetoric would have provided a fuller picture of religious responses to the Revolution, these groups left a scant documentary trail because of the nature of their communities and their worship.

Byrd also seems not to have noticed that the most bellicose sermons he quotes came from Presbyterian ministers—not Congregationalists or Methodists or even Baptists. Did most such sermons indeed come from Presbyterians, and if so, why? (His database appears to have contained only biblical references, not the denominational provenance of the preachers or even their geographical location.) Is the apparent Presbyterian predominance because of their regional concentration in the middle colonies, or is it because of Scottish and Presbyterian antipathy toward the British dating back for generations?

These are quibbles. Among the other contributions of this fine study, Sacred Scripture, Sacred War demonstrates the convulsive and tragic nature of war, which not only makes citizens into soldiers but also transforms the Prince of Peace into a Mighty Warrior.