Dark fantasy novels that scream theology

I didn’t expect so much sacramental imagination in Tamsyn Muir’s series about lesbian necromancers in space.

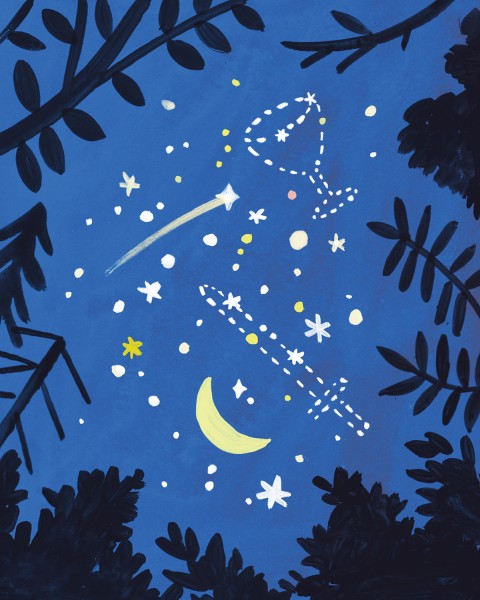

Illustration by Tallulah Fontaine

In divinity school I took a class with Matthew Potts, a religion scholar and Episcopal priest, called Sacramental Imagination. In it, we read Cormac McCarthy’s The Road and Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son and watched Gabriel Axel‘s film adaptation of Isak Dinesen’s Babette’s Feast, mining them for their sacramental moments. The father in The Road bathing his boy in a freezing pond, pouring water over his head. The addict protagonist of Jesus’ Son, crouching outside a window, watching a husband wash his wife’s feet. Babette preparing a feast, the likes of which had never been seen in her dour little town, and foreclosing options to herself out of love for the sisters she works for.

While fictional, these are stories about real life: about the ways that the world is dark or difficult or nearly unsurvivable. And each of them contains these sacramental moments like the pinpricks of stars, showing how familiar rituals can carve out time in the darkness that is devoted to beauty and reverence and connection. Sometimes to the Divine, sometimes to other people.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I think the main thing I took away from that class is that, yes, the sacraments are things that are about God, about building and maintaining and expressing a relationship to the Divine, but they are also things we can do to and for other people, a specific way we can give of ourselves. It also taught me to read differently—in a way, to be able to pick out the threads of Christian meaning that so often lurk in the back of books, movies, popular culture, and, to be honest, my own mind. The baptisms, the communions, the little acts of care refracted through a Christian lens. And nowhere was I more surprised to find them than in Tamsyn Muir’s The Locked Tomb series.

The Locked Tomb series spans three books (with a current, rabidly awaited fourth somewhere in the works) following, well, as the tagline says, “Lesbian necromancers in space.” I have probably reread the first book, Gideon the Ninth, about once a year since I picked it up for the first time, based on the fervent, all-caps recommendations of some of my closest friends. By page 3, I was utterly smitten by Gideon Nav, the redheaded, sword-wielding, desperately lonely himbo main character, who is trapped in a years-long rivalry with the only other young person on her planet, the also desperately lonely, fiercely ambitious Reverend Daughter Harrowhark Nonagesimus. Gideon is forced to be Harrow’s cavalier—her sword and shield maiden—while Harrow tries to attain sainthood.

The voice is absolutely unique, swinging between high fantasy registers and memes; the world-building is dense and complex and wonderful enough to reward multiple readings. I would describe Gideon the Ninth as being something like a mix between The Secret History and The Name of the Rose. It’s goofy and fun, swashbuckling and fairly gory, but also absolutely replete with the sacraments. I would not have been surprised if Matthew Potts had turned midsemester from The Road to Gideon the Ninth and spent a full week of class talking about the deeply entrenched theology of these books.

And this theology is not an accident! Muir has, I think, genuinely read everything: the Bible, Augustine, an absolutely gargantuan amount of fan fiction classics. As you’re reading the book, a stray bit of language catches at the corner of your brain and you think, Wait—is that Judith Butler? Why else would Harrow say to Gideon, “I am undone without you,” a line from one of my favorite Butler essays about grief and action? Is this scene meant to be a callback to Peter’s denial of Christ? Is the entire central mystery of the first book a sort of Eucharist gone sideways?

The answer to all these questions, as far as I can tell, is yes, yes, yes! The further you get into the series, the more the foundational world-building starts feeling like “what if an early Christian heresy got really, really weird,” and the more the kind of biblical hermeneutics I learned to apply to fiction in Potts’s class feels rewarded in the text.

But I think the real reason I love The Locked Tomb series is not just its absolutely crunchy set of references. It’s the fact that these references all point back to one thing: the efficacy of the sacraments, and the way they are tied up in the people we celebrate them with. The books take place in a universe that is often more obviously dark than our own—the magic system and power structure are all based on death energy, meaning that plays for survival and power often come at great, visible cost. Harrowhark spends her entire childhood torturing Gideon, punishing her for the crime of being alive, and they are now trapped in a horrifying murder mystery game with each other as partners.

Into all this darkness come the real rituals of the church—set on their ear, queered, made horrifyingly literal, but recognizable as themselves—and each time, they enact change. When Gideon and Harrow enter a saltwater pool, they emerge with their sins washed clean:

Gideon braced her shoulders against the weight of what she was about to do. She shed eighteen years of living in the dark with a bunch of bad nuns. In the end her job was surprisingly easy: she wrapped her arms around Harrow Nonagesimus and held her long and hard, like a scream. They both went into the water, and the world went dark and salty.

The scene is a sacrament, but it’s also the beating heart of the relationship between the two girls.