Faith-based groups, others put pressure on UN for its role in Haiti cholera deaths

Every family in Joseph Dade Guiwil’s community has been harmed by the cholera epidemic in Haiti, the worst outbreak in recent history.

“I say to the UN: give us justice,” Guiwil told Katharine Oswald of Mennonite Central Committee, a Christian relief and development organization.

United Nations peacekeepers have been found to be the source of the cholera outbreak that began six years ago and has killed thousands. MCC has joined other faith-based organizations, Haitian groups, and others in a call for the UN to accept moral responsibility.

“This call for justice for cholera victims in Haiti has been strong and consistent throughout the past six years,” Oswald said.

The devastation of Hurricane Matthew in early October left people with even fewer resources to prevent cholera, which often spreads through contaminated water and causes dehydration that can kill people within hours if they do not receive medical attention. The hurricane ripped away cholera prevention centers as well as health-care facilities and people’s latrines, said Oswald, who has been based in Port-au-Prince with her husband, Ted Oswald, for the past two years but who is currently working in the United States.

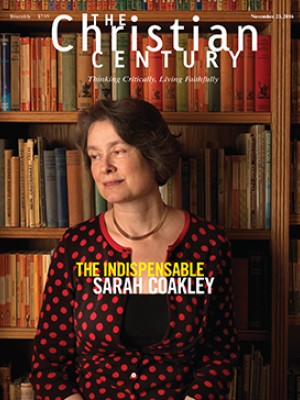

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

As nongovernmental organizations and state authorities respond to the thousands of new infections since the hurricane, some groups are continuing to put pressure on the UN to take responsibility for introducing cholera to Haiti.

“There was waste that was improperly disposed of that leaked into a tributary that spread into the Artibonite River, which is Haiti’s main water source,” Oswald said. “It just hit like wildfire.”

Scientists traced the bacteria in the river to a base of UN peacekeepers from Nepal.

“The particular strand of cholera that was found to contaminate the river is the same strand that is endemic in Nepal,” Oswald said. “It was not obvious at all that these troops had cholera, but they were carrying it.”

The UN did not screen its peacekeepers before sending them to Haiti, which is something that groups advocating for victims have been pushing for as a standard practice, as well as more caution with sanitation, all around the globe.

Philip Alston, an independent expert on extreme poverty and human rights, wrote a report on the UN’s response to cholera in Haiti, which was not present previously. On October 25 he told the UN General Assembly that “while the UN has for the past six years ignored claims by victims for a remedy, focusing exclusively on measures to contain the outbreak,” the UN’s recent efforts show improvement in eradicating the disease and helping those afflicted by it.

“The bad news is that the UN has still not admitted factual or legal responsibility and has not offered a legal settlement as required by international law,” Alston told the UN, according to the UN News Service.

The Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti, based in Boston, and its Haitian partner, Bureau des Avocats Internationaux (Bureau of International Lawyers), filed 5,000 claims with the UN in November 2011, seeking a national water and sanitation system, compensation for victims, and a public apology.

More than 840,000 people have been infected, and more than 10,000 have died, the IJDH reports, drawing on studies suggesting the official counts have been underestimated.

After the UN said it would not receive the claims, IJDH, BAI, and other attorneys filed a suit against the UN in New York federal court.

In August, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the UN’s claim to immunity. The attorneys have not yet decided whether they will appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Around the time of the appeals court ruling, a draft of Alston’s report was leaked to the press. A representative for Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said in a statement: “The United Nations has a moral responsibility to the victims of the cholera epidemic and for supporting Haiti in overcoming the epidemic and building sound water, sanitation and health systems.”

The statement made in August “felt like a great milestone,” Oswald said. But questions remain about how far the UN will go in its response.

Brian Concannon, executive director of IJDH, said that the organization’s advocacy efforts for victims were not merely “about winning a court case. There were lots of important parts of it.”

The UN has talked about providing material assistance to Haitians affected by cholera, though the amount Concannon has heard mentioned—$200 million, which the UN describes as “a support package to reach those immediately affected”—would not constitute justice for the victims in his view.

“There were real losses to the people,” Concannon said. Cholera affected people who “were so poor that they couldn’t afford a little bit of money for treated water.”

A lot of families went into debt because of lost income, funeral expenses, and other costs.

The compensation could come through a mix of cash payments to families and through contributions to community projects and rebuilding.

“Kids who lost their parents, they need money,” he said, while others might be satisfied with the building of a school in their community, for example. “It’s important to consult with them and to make sure that the victims feel that justice has been done.”

IJDH and MCC were two of the organizations that have collaborated in the Face Justice campaign for the past year. Other faith-based groups, including the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) and Church World Service, joined the effort to bring attention to the stories of victims and survivors.

The network also included lawyers, scientists, and doctors, Concannon said. Each was doing separate work, but it benefited the other efforts.

“This collaborative, network-based strategy,” he said, “is exciting and a template for how you can do broad social change.”

Oswald noted that some NGOs working in Haiti “are reticent to use the language of obligation related to the UN.” Yet among the groups who have worked together on advocacy for eradicating cholera, “every group can say that none of this would have been possible without the other.”

Part of what MCC contributed was the work of people on the ground in Haiti for the past six years. As part of the Face Justice campaign, the Oswalds interviewed survivors and family members of victims in the countryside and around Port-au-Prince. Some families lost their main breadwinners. Older parents lost their adult children and are left with no one to care for them.

Olivia Jean-Pierre described how her two teenage daughters became sick with cholera in 2011. She has sought reparations for cholera victims alongside other families since then.

“My girls haven’t yet become 100 percent again,” Jean-Pierre said. “They go to school and put their heads on their desks, saying their heads hurt. They used to be such excellent students.”

Silana Dozeis, a single mother of four, lost her home in the hurricane, she told Ted Oswald.

“So many people here have been sick with cholera, many have died,” she said, and now she fears for her children. “When I saw the water I had to give them to drink after the storm, I cried.”