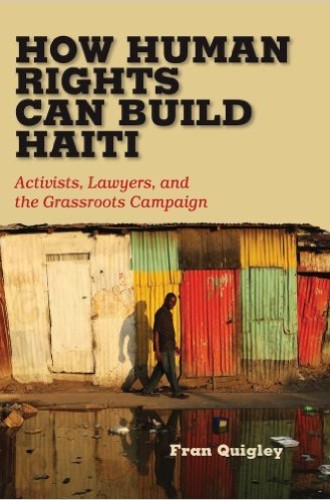

How Human Rights Can Build Haiti, by Fran Quigley

Whenever I return from Haiti I am asked if there is any hope for the country. I reply that when I am in the United States and hearing the news I do not think so. But when I am in Haiti among Haitians I believe there is.

The internationally known physician and anthropologist Paul Farmer, whose legendary work in Haiti began in the 1980s, sometimes says that the sickest patient on the island of Hispaniola is Haiti’s public sector—its government and its public infrastructure, including roads, bridges, sanitation systems, health care, and education. The efforts of most nongovernmental organizations, including the many churches that send mission groups to Haiti with the best will in the world, do nothing to strengthen the public sector. Hence the effects are short term. Their efforts are like dressings applied externally to wounds that come from internal, systemic disease.

Fran Quigley’s richly informed study of what ails Haiti and what a few dedicated activist lawyers are doing about it includes this comment by a consultant for the United States Agency for International Development: “I wish I could organize a trip of Tea Party activists and take them to Haiti so they could see what happens if they have a country with no government.” Quigley, who is director of the Health and Human Rights Clinic at Indiana University’s McKinney School of Law, offers plentiful information about the causes of Haiti’s miserable economic condition, chiefly its weakened government and the exploitation of Haiti’s poor by the country’s wealthy elite, often in collaboration with U.S. business interests.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The focus of his book, however, is the work of two NGOs that are offering to Haiti something different from and more lasting than material aid. The Bureau des Avocats Internationaux (BAI)—Bureau of International Lawyers—and its sister organization in the United States, the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti (IJDH), are working nonviolently for fundamental change.

BAI was founded by then-president Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 1994, when Haiti’s democracy movement was at the height of its influence and had not yet been decimated by the reactionary forces that managed to remove Aristide from the country in 2004 and to exclude his democratic party, Fanmi Lavalas, from the ballot box thereafter. Aristide staffed BAI with non-Haitian attorneys and charged it with assisting the Haitian government to prosecute human rights violations. The aim, as Quigley puts it, was “to bring the talents and resources of international lawyers to the process of reforming the Haitian justice system.” The public sector cannot be healthy unless it is protected by a robust judicial system, and the plan was to strengthen the muscle of the judiciary by using it to protect human rights. BAI filed and argued human rights cases in the courts and kept them in public view through community organizing at the grassroots level. In spite of frequent setbacks, the concept is sound, and the work of both BAI and IJDH has been brilliant.

One of the international lawyers employed by BAI was Brian Concannon, a son of Irish American parents in Boston and a graduate of Georgetown University’s school of law, who formerly served in Haiti as a human rights observer for the United Nations. Once he came to BAI, he and others decided to bring Haitian attorneys into the bureau as well, and it fell to Concannon to hire them. Whether because of sound instinct or good luck or both, one of the two lawyers he chose was Mario Joseph.

Born into poverty and raised without a father in the home, Joseph managed to get himself through law school and began his career with a Catholic Church justice commission, representing people who had been repressed by Haiti’s military-coup government during Aristide’s pre-1994 exile. He joined BAI in 1996 and today enjoys an international reputation among human rights advocates. Joseph has received many awards but also several death threats, mostly when he pursued cases against the former dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier, who died in October 2014. His office has also brought suit against the United Nations for its responsibility for the cholera epidemic that began in Haiti in October 2010, as well as suits against rapists and other violators of human rights.

Concannon continued to work for BAI in Haiti until 2004, when he decided that he could be of more use to Haiti in the United States. Joseph then took leadership of BAI in Haiti while Concannon founded IJDH in the United States to lobby federal officials, disseminate information, and raise funds.

BAI’s accomplishments are many, and Quigley describes and interprets them with skill. For example, BAI successfully prosecuted the army officers who authored an infamous massacre in Raboteau in 1994, facilitated community organizing among rape victims in tent cities after the 2010 earthquake (when neither the police nor the UN force were providing safety), and achieved the release of political prisoners such as Father Gérard Jean-Juste, who was falsely accused of murder—this after Concannon successfully organized advocates in Indiana who spurred Senator Richard Lugar to intervene.

Like Mario Joseph, many Haitians refuse to let the odds against success rob them of hope and perseverance. But Joseph is unlike many Haitians in his belief that he can succeed in the pursuit of justice. He has produced a record strong enough to keep that hope alive by following a strategy to achieve lasting change in Haiti’s distorted system of government.