Connections that last

Whenever I visit my parents in Kentucky, we make the rounds of our holy places: first, a visit to our favorite bookstore; next, a trip to the Abbey of Gethsemani for vespers and compline. Then we visit the Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill, a living museum known to the locals as Shakertown.

Like Shakers everywhere, the Shakers who made their home in Kentucky sought to create a paradise. They shared their goods communally. They practiced equality. They lived celibate lives so that erotic attachments would not hinder their common life. They worshiped God with dances taught to them by angels in dreams and visions. And they created buildings, tools and furniture that are works of art. As Thomas Merton wrote, what makes a Shaker chair so beautiful is that it was made by “someone capable of believing that an angel might come and sit on it.” The creation of every room, every staircase and every table was, for the Shaker craftsperson, a prayer.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I love the buildings in Shakertown most of all. There is something about the way they occupy space that makes them seem an organic part of the landscape. They are profoundly still, yet seem on the verge of speaking. They seem perfectly proportioned, silent and in tune with the space around them and the sky overhead. Like Merton, I imagine moving into one of them just to hear the silence, just to watch the light moving through the rooms.

A few weeks ago I made a pilgrimage to my own local Shakertown, the Hancock Shaker Village in western Massachusetts, to see an exhibition of photographs of Shaker villages in Massachusetts, New Hampshire and New York made by WPA photographer Noel Vicentini, who was hired by the Federal Art Project in 1935 to document Shaker art for the Index of American Design. In our age of political gridlock, it is startling to remember that our government once launched an ambitious jobs program, one that regarded artists as workers whose work could help the nation explore what it means to be an American.

Vicentini photographed the Shaker villages nearly a century after Shaker artist Hannah Cohoon painted the trees of life, blazing with energy, that came to her in visions during the years when the buildings were full of Shakers. Vicentini captured the end of that quiet paradise, Eden going to seed. The few Shakers who appear in his photos look careworn and isolated. The buildings are marked by broken windows, cracks in walls and ceilings, water damage and missing clapboards and shingles. Dark clouds hover over many of the photos, and weeds grow up around the magnificent round stone barn in Hancock. Vicentini shows us what it looks like when something precious is coming to an end.

It is interesting to see what captured Vicentini’s attention at this moment of disappearing. He had been sent to document uniquely American art, and many of the photographs are familiar Shaker images: the single bonnet hanging on the peg board, the empty room filled with light. Vicentini captures the stillness and eloquence of the buildings even as shingles slip from their roofs.

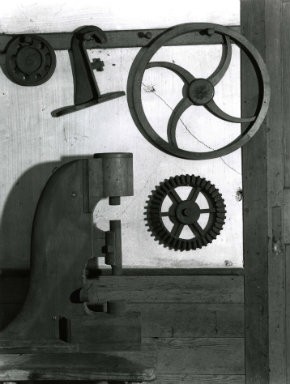

Vicentini seemed most interested, however, in the places where one thing attaches to another: a bridge connecting two buildings, a drainpipe attached to a wall, a latch on a door. Vicentini seemed to find in these places of joining something fundamental about the Shaker art.

The Shakers have not disappeared from the earth—a community in Maine is alive and well—but Shaker life in the villages that Vicentini photographed did come to an end. His photographs bear witness both to the coming end of a community and to what remained: an American art in which function and need inspired forms of great beauty created by men and women who drew near to their God through their work. The art continues to speak even though its creators have fallen silent.

It is hard to look at Vicentini’s photographs and not wonder what museumgoers a century from now will see of our lives in another time when so much seems to be slipping away—from the ice at the top of the planet to our country’s infrastructure to certain kinds of jobs or particular forms of religious life. What will disappear, and what will remain from our own in-between time? When he photographed the disappearing Shaker villages, Noel Vicentini seemed to find continued life in the places where one thing had been joined to another: a handle attached to a door or a latch so carefully crafted that it closed perfectly every time. He took detailed, up-close photographs of these things so that Americans of the future could study them and learn something about the relationship between Shaker design and who we are.

Perhaps one thing we can learn from his efforts is that finding useful and beautiful ways of joining one thing to another—or one idea to another, or one person to another, or one community to another—matters, and will continue to matter even as so much else comes to an end.