The mass finds its voice

I first encountered the mass in midair. At least, that's how it felt. I was lying on my stomach on the living room carpet in a Manhattan apartment 13 stories above ground, listening to my parents' recording of Bach's Mass in B Minor. I had never attended a religious service of any kind, but with the help of liner notes that included the ordinary of the mass in Latin and a literal English translation, I was able to follow along. For several years the "Qui tollis peccata mundi" haunted my consciousness; in college it became an instrument of my conversion. Later on I learned that Bach had adapted a melody from Cantata 46 ("Schauet doch und sehet" / "Behold and see") to serve the Latin text common to Lutheran and Catholic worship. It was an inspired act of translation, wedding a universal language of Christian worship to a musical vernacular.

The second time I heard the mass I was stretched out on the same carpet listening to my parents' 1963 Philips monaural recording of Missa Luba, an exuberant setting of the mass sung by a Congolese (Luba) boys' choir. A Belgian Franciscan had found a way to unite the call-and-response improvisational singing of the Luba people with the universality of the Latin words. Once again, I could follow along thanks to a faithful English translation. Those liner notes became my missal and catechism.

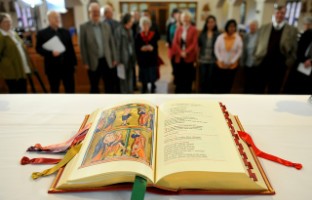

Much has changed since then—in the year Missa Luba was published, the Roman Catholic bishops at the Second Vatican Council approved the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, calling for a revision of the liturgical books in the light of biblical and apostolic sources, with the aim of deepening awareness of the Eucharist as the central mystery of Christian life. With regard to music, "pride of place" was reserved for Latin Gregorian chant, with generous scope for polyphony. The document also sanctioned vernacular translation of the Roman missal, on the understanding that the Latin original would provide the norm, the measure and the ballast for the translators' art.