Slow-motion conversion

It is by living and dying that one becomes a theologian, Martin Luther said. With that comment in mind, we have resumed a Century series published at intervals since 1939 and asked theologians to reflect on their own struggles, disappointments, questions and hopes as people of faith and to consider how their work and life have been intertwined. This article is the third in the series.

On July 11, 1991, the Feast of St. Benedict, I was baptized and received as a Catholic in the chapel of the twin Benedictine communities of St. Mary’s Monastery and St. Scholastica Priory in Petersham, Massachusetts. Any views I’ve acquired since then pale in significance, washed out in the light of the gospel and creed I accepted on that day. Yet a gradual change began then, and continues to the present, as I assimilate the effects of baptism and confirmation. No doubt there are corners of my mind that still haven’t heard the news.

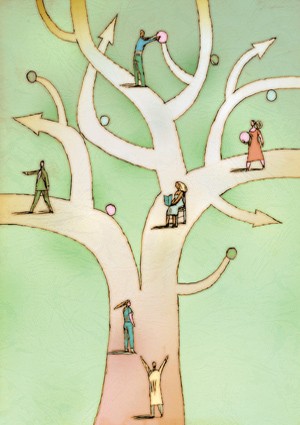

Mine was a slow-motion, book-driven conversion. For many years I ran on two tracks. Along one track, I inched toward the church. I longed to press forward, forgetting what lies behind, as St. Paul writes (Philippians 3:13–14, a key text for Augustine’s Confessions and thereafter for countless narratives of Christian conversion), but nonetheless I held back, searching and temporizing, out of respect for my Jewish heritage. Since my upbringing had been wholly secular, whatever I knew of Judaism and Christianity came to me mainly through reading. The chief influences were Augustine, Anselm and the monastic theologians of the 12th century, in whose writings I caught sight of a country I longed to inhabit but—I know this will seem strange—didn’t know where to find.

I met Christ in my studies, but it took much longer to get to know the church. I found in the works of Marie-Dominique Chenu, Étienne Gilson, Jean Daniélou, Emile Mersch, and especially in Henri de Lubac’s four-volume Exégèse médiévale, a Baedeker to this distant native land. But I had no inkling of the role that some of these thinkers had played as figures in the ressourcement movement that informed the Second Vatican Council. I knew nothing of the supposedly arid neo-scholasticism that was being overthrown—and is now being rehabilitated. I had barely heard of Rahner and Lonergan. I read Karl Barth enthusiastically but naively, as if he were a second Kierkegaard, and Hans Urs von Balthasar as a transmitter of patristic wisdom. I held a key in my hand, and it almost rusted there.

On the other track, I was a student of world religions, trained in the latest theoretical approaches—a devoted reader of Mircea Eliade, Rudolf Otto, Gerardus van der Leeuw, and Carl Jung, a student of classical Indian Buddhism, interested in mythology, iconography, philosophical yoga, folklore and visual culture, and at the same time a product of a graduate theology program that involved grappling with Enlightenment and modernist thinkers. Studying world religions while reading medieval Cistercians and 19th-century Romantics gave me a taste for symbol and sacrament, but, unchurched as I was, I could not fully grasp the gulf between religion as object of study and the church as supernatural reality.

Funny things happened whenever these two tracks crossed.

In my first book, Otherworld Journeys (1987), I made a comparative study of medieval and modern accounts of near-death experience, highlighting the cultural factors that shape visionary experience. As a historical and comparative exploration, the book still seems sound. But there are a few pages in which I venture into theology and go off the rails:

Theology . . . is a discipline of critical reflection on religious experience and religious language. As such, no matter how objective or systematic it becomes, it cannot escape the fundamental limitations that apply to religious discourse in general.

. . . although theology involves analytic thought, its fundamental material is symbol. Its task is to assess the health of our symbols; for when one judges a symbol, one cannot say whether it is true or false, but only whether it is vital or weak. When a contemporary theologian announces, for example, that God is dead or that God is not only Father but also Mother, he or she is not describing the facts per se, but is evaluating the potency of our culture’s images for God—their capacity to evoke a sense of relationship to the transcendent. . . .

To say that theology is a diagnostic discipline is also to say that its method is pragmatic. . . . We must judge those images and ideas valid that serve a remedial function, healing the intellect and the will. In this sense, all theology is pastoral theology, for its proper task is not to describe the truth but to promote and assist the quest for truth.

You see, I was trying to acknowledge all the factors—medical, psychological and sociological—that contribute to mystical and visionary experience, while removing the reductionist sting from such explanations. I was trying to defend the right of individuals to believe in their own experiences, without resorting to protective strategies. I was trying to clear away the obstacles to wholehearted religious belief and practice, while admitting that religious belief and practice are culturally shaped. I thought William James could help me with this project.

But what a jumble of half-baked epistemological ideas crowd the above paragraphs! Despite what I said, I must not have believed it possible for theology to be truly objective or systematic. Therefore I cobbled together a Barthian sense of the unfitness of the human instrument, a Romantic value for imagination, a mystical apophaticism, a commonsense pragmatism and a false deference toward passing fashions (for, to be honest, I never took seriously the suggestion that God should be described as Father/Mother, let alone the idea that God is dead). The principle of divine transcendence I invoke is unobjectionable in the right context—I might simply be echoing Augustine’s si comprehendis non est deus (if you understand him, he is not God)—but the all-important countervailing principle of revelation is occluded.

Perhaps this is understandable, for I was writing as an uninitiate, whose relation to theology was idiosyncratic and bookish. Though by this point I had read searchingly in the spiritual writers of the 11th and 12th centuries, under the tutelage of Caroline Bynum and Arthur McGill, my education as a graduate student in theology had been largely taken up with Kant, Coleridge, Schleiermacher, Husserl and James. I still love these thinkers for their genius and good will, and feel immense gratitude to Richard R. Niebuhr and the other generous teachers who introduced me to them. Yet I lacked the means to systematize these diverse perspectives. I was by turns a Christian Platonist, a neo-Romantic and a historicist interpreter of the religious imagination. And all the time, the integrating vision I needed lay hidden in the catechism.

Readers of Otherworld Journeys often say to me, well, yes, this is all very interesting, but what do you really think is going on in near-death experience? The short answer is that I consider near-death experience no different from other visions or private revelations, for which the standard methods of discernment should be employed, taking into account the relevant naturalistic explanations without dogmatically ruling out or credulously ruling in a supernatural origin. I am distinctly unimpressed by claims of the paranormal and consider psychical research a tawdry substitute for religion. My default setting when it comes to visionary testimony is at once sympathetic and skeptical. The right to believe is precious; the capacity for self-deception is boundless. My belief in life after death rests on entirely different grounds.

A better index of what I think as a Christian about death and afterlife can be found in the Ingersoll lecture I gave at Harvard in 2000 and in the little book, The Life of the World to Come: Near-Death Experience and Christian Hope, based on the Albert Cardinal Meyer lectures I gave at Mundelein Seminary in 1993. By then I had rejected the constructivism I was flirting with in 1991. To the “yes, but what do you really think?” question, I had a new answer to give:

If God is willing to descend into our human condition, may he not also, by the same courtesy, descend into our cultural forms and become mediated to us in and through them? To deny that this courteous descent can take place is to reinvent the heresy of the iconoclasts.

Such a katabasis would transfigure our all-too-human forms, so that they no longer serve merely self-serving ends; this is one test of a genuine religious symbol. But no matter how genuine, the symbol can never become completely transparent to the reality it represents. We cannot know what awaits us after death, but we can legitimately believe all that our tradition teaches and our experience suggests. We believe all this under correction, and—if we love a good surprise—we look forward to the correction.

The truth about eschatology is itself eschatological. Now we see in an enigma darkly, in the mirror of our culture. Only “then,” when the veil is lifted, shall we see face to face. Now we must test the soundness of our images and symbols by practicing the traditional and modern arts of discernment, guided by both dogma and experience. Only then shall we know as we are known.

I can almost trace my footsteps, in this passage, from the symbolo-fideism that kept me going through the 1980s and 1990s toward the theological realism that has become my more settled lodging. The key word comes at the end: dogma. In the environment in which I was writing it was almost an incendiary word, but in my private thinking it was one of surpassing loveliness. Think dharma, I tell my Buddhist friends, and you will understand why the word dogma sounds beautiful to my ears.

William James, whom I have regarded as something exceeding an influence and approaching an uncle, ought to have made dogma anathema to me. If I were a true Jamesian, I should be writing about how my mind, unhindered by dogma, is incessantly changing. “The wisest of critics is an altering being,” James writes in The Varieties of Religious Experience, “subject to the better insight of the morrow, and right at any moment, only ‘up to date’ and ‘on the whole.’ When larger ranges of truth open, it is surely best to be able to open ourselves to their reception, unfettered by our previous pretensions.”

I still find much to admire in the intellectual humility of this passage. But the wisest of critics is an altering being, and I have altered mainly by swimming upstream against the currents to which James introduced me, from personal religious experience “immediately and privately felt” to worship objectively offered; from theology as therapy to theology as queen of the sciences.

The dogmatism I now wish to recant is the dogmatism that blinds us to the beauty of dogma. Intellectual humility is one thing, but I began to realize that it is just as arrogant to withhold certitude indefinitely as it is to arrogate to oneself or one’s cohort the power of attaining it. Certitude, in response to revealed truth, is founded on trust in the Holy Spirit, not in our own cleverness.

So I moved on, without alienation of affection, from William James to another 19th-century genius: John Henry Newman. Newman and James are kindred spirits in their personalist understanding of the search for truth, as well as their candid, affecting, colloquial, crystal-clear and beguilingly convincing prose style. Yet Newman’s famous saying, “to live is to change, and to be perfect is to have changed often” is worlds apart from the untethered experimentalism James espouses. Personal conversion, yes, this is the heart of the matter for both Newman and James; but considered in context, it’s clear that Newman’s saying pertains to how the mind of the church as a whole changes, by organic development of what is implicit in the deposit of faith—in other words, by the gradual unfolding of dogma. “From the age of fifteen,” Newman writes, “dogma has been the fundamental principle of my religion: I know no other religion; I cannot enter into the idea of any other sort of religion; religion, as a mere sentiment, is to me a dream and a mockery.” How I would love to introduce Newman and James to each other and hear them hash this out. In the meantime, I keep The Development of Doctrine and The Idea of a University on a small shelf of favorite books right next to The Varieties of Religious Experience.

My love of other religions has only deepened over time. Above all, I feel more Jewish than ever, thanks in part to the influence of our philosemitic Benedictine friends, the philosemitic pope John Paul II and the experience of monastic psalmody. I understand more clearly than ever the urgent need to reject supersessionism and establish on unshakable footing the Christian recognition of the permanence of the covenant between God and Israel. I believe that the fidelity of Jews to Judaism is an essential part of the universal plan of salvation. I cringe when I look in our church hymnal and find those folksy tunes that vocalize the Tetragrammaton. My husband, Philip, and I have been reading Rashi and dipping into the vast ocean of the Talmud. I’ve read the Hebrew Bible in its Tanakh order (Torah, Prophets, Writings), though not, I confess, in its original Hebrew. Nonetheless, I have no wish to adopt an artificial dual practice. When I read the Psalms devotionally, I follow the christological interpretation that is integral to the Bible of the church.

I feel an instinctive kinship with people of all faiths who are trying to live out of the heart of their religious traditions. It seems natural to make common cause with them on a host of cultural and social issues, including respect for human life from womb to grave. We have a close friend who came to this country as a refugee from eastern Tibet, where he had lived in a Buddhist monastery of the Nyingma sect from the age of five. He settled eventually in our town, married and raised a family, and has sustained the practice of his ancient sacramental religion. We see eye to eye with him and his family on the deepest moral and aesthetic questions, not least of which is belief in the reality of sin and the need for redemption.

It is a striking fact that, though conceptions of sin vary widely, all the world’s religions recognize that there is something fundamentally awry with us, not merely maladaptive. I like this little ditty of John Betjeman’s: “Not my vegetarian dinner, not my lime-juice minus gin, / Quite can drown a faint conviction that we may be born in sin.”

How else to explain our repeated failure to be human, the crude uses to which we put our exquisitely sensitive brains and hearts? Very little makes sense on any other view. But the belief in sin that Christians share with all traditionally religious people is fundamentally hopeful, for it implies that the cosmos has a moral structure and can be counted on to provide a means of liberation and cure.

I look to other religions not with a view to borrowing spiritual techniques or conceiving schemas of their ultimate unity, but simply because there is so much to learn from and admire in the integrity of a fully realized religious culture and in the works of holiness and beauty it inspires. I agree with T. S. Eliot that the Bhagavad Gita is, after the Divine Comedy, the greatest philosophical poem in world literature. Yet I have no desire—indeed, I have no right—to concoct a doctrinal or practical synthesis out of these or any other masterpieces of the great traditions.

Once upon a time, under the influence of some students of G. I. Gurdjieff, I overvalued the cultivation of attention (or mindfulness) as a religious discipline. I even proposed that attention could be a key to Buddhist-Christian dialogue. I am no longer so interested in that kind of interreligious dialogue. Once upon a time, I believed that Christianity was impoverished, compared to Buddhism, when it came to methodical spiritual disciplines. That was either ignorance or misplaced emphasis.

Once upon a time I planned a book on religious experience. If I were to salvage that book now, its subject would be adoration. Adoration is our purpose; it draws us toward our creaturely completion. While religious experience can be triggered by all sorts of constructs, images and narratives, adoration is appropriate only in the presence of the absolute divine object, worthy of the bended knee and prostrate form. Adoration is supremely reasonable and objective; rationality is itself a form of adoration.

The shift in emphasis from subjective religious experience to objective religious practice is reflected in the book on prayer that I coauthored with my husband. We wanted to call the book The Language of Paradise, but the publisher opted for Prayer: A History. It is not, in fact, a history but an extended essay on prayer in its varied forms: petition, intercession, contemplation, liturgical prayer, penitential prayer, ecstatic prayer, literary prayer and so on. We took issue with Friedrich Heiler’s classic book on the subject, Prayer: A Study in the History and Psychology of Religion (1932), in which he says that prayer is “a spontaneous emotional discharge, a free outpouring of the heart” which by a “process of petrification and mechanization,” eventually hardens into rites and formulas. On the contrary, we argued, prayer is a gift, but the life of prayer is the cultivation of that gift, not simply its spontaneous discharge; and the life of prayer in turn generates culture.

One still hears complaints about the “institutional church” —the very expression betrays a parti pris. But how would we know Christ without the institutional church? Who else would preserve the great secret of the gospel for us through the centuries, keeping it safe in the wilderness of opinions? We live in a world of institutions or in no world at all, and the institutional church is surely the greatest institution the world has ever known. It is the mediating institution between the family we are thrust into and the government that is either forced upon us or chosen by us from a distance. It equips us with every grace, every insight, every support for a decent life and then, like so many parents, is disappointed but not surprised when we turn around and say—we don’t need you, we can do this on our own, you are a fossil, an impediment.

Do we have more reason to trust experimental, free-floating forms of religious life? Give me an institution any day, a big sprawling, international one, where authority resides in structures and traditions and is not invested in particular personalities; where my own personality is of little account, and yet I get to keep it. The ship of faith has its anchorage in the world, and I thank Constantine for it.

I believe that God’s loving will guides the path of galaxies, subatomic particles and human events. I believe in design, as Newman does, “because I believe in God; not in a God because I see design.” And I believe that the design is marred by a Satanic power that works continuously to pervert it. But I am slow to read history suprarationally in light of this belief. Perhaps this is a vestige of the Tychism I took from William James, but I believe there is room for chance in God’s design for nature and history.

The well-established findings of Darwinian science do not perturb me, especially when I reflect that ours is a fallen world in which God’s plan for creation is obliged to unfold by means of death (“nature, red in tooth and claw”). How it might have been otherwise in an unfallen world, we cannot know.

I believe in the soul and continue to defend old-fashioned soul-language against the dehellenization program that was fashionable in the 20th century. I admit all that cognitive and neurological science can teach us about the physiological basis for consciousness and personal identity, but find that with every advance in this field, the mystery of self-awareness (the so-called “hard problem” of consciousness studies) only grows deeper.

I find much to admire in recent theological writing, especially when its expression is graceful, humble, free of academic jargon, historically sensitive and not agenda-driven. I’m drawn to contemporary thinkers who highlight self-surrender as the essential Christian disposition, but I don’t think that this spiritual insight must entail the rejection of Cartesian, Aristotelian or Platonic ontology. I’m glad to see that, after assimilating Karl Barth’s purifying critique, many Christian thinkers are rediscovering the classic arguments for the existence of God and the permanent viability of natural theology. As ever, the mysteries of the triune God and of God’s image in man are an inexhaustible subject for creative theological reflection. Nonetheless, I find some recent investigations of the inner, even erotic, life of the Trinity embarrassingly over the top. The best theological writing is slow to advance bold new themes. Always seeking to be true to the mind of the church, it arises out of and returns to prayer.

It’s often said that we no longer live in an age of theological giants. Nonetheless, until the next age of giants comes around, theology still has its tasks to perform. There may even be some spiritual benefit from the loss of prestige. I like to imagine how theology would look if its production were, for the next decade or so, an anonymous affair. Then we would have no one to lionize as the successor to Athanasius, the courageous dissenter, or the discerner of new meaning-horizons for our time. Then theology could continue on its patient, plodding, pilgrim path, seeking God’s face, alive to historical development, celebrating the rational beauty of the cosmos, reading the Bible in the light of the cumulative experience of the church, sensitive to social needs and crises but unfazed by passing cultural fashions.

As Augustine says, “I have been dispersed into times whose order I cannot fathom.” Memory is unreliable. Yet if the two tracks I’ve been running on seem closer together now, and if (as I hope) there is more evangelical simplicity in my recent writings, I owe it mainly to the personal influence of my family, my godparents, our Benedictine monastic friends and a few others. God only knows how far my mind has wandered off into the shadowy “region of unlikeness” or how far it has stayed the course, forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead.

Other installments in this "How my mind has changed" series:

Turning points, by Paul J. Griffiths

The way to justice, by Nicholas Wolterstorff

Christian claims, by Kathryn Tanner

Lives together, by Scott Cairns

Reversals, by Robert W. Jenson

Deep and wide, by Mark Noll