November 22, RoC (Matthew 25:31-46)

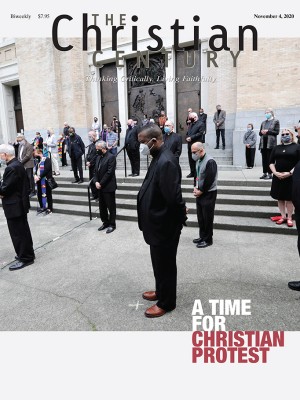

On Christ the King Sunday, let’s disentangle Jesus from the idols of our time.

Christ the King Sunday is one of the more recent additions to the Western liturgical calendar. Pope Pius XI instituted it in 1925, when, as Silas Henderson writes, “a world that had been ravaged by the First World War . . . had begun to bow down before the ‘lords’ of exploitative consumerism, nationalism, secularism, and new forms of injustice. . . . Pope Pius envisioned a dominion by a King of Peace who came to reconcile all things, who came not to be served but to serve.”

A very quick historical survey of 1925 reveals the following events:

- Benito Mussolini dissolved the Italian parliament and became a dictator.

- US president Calvin Coolidge proposed phasing out the inheritance tax.

- In Munich, Adolf Hitler resurrected his political party.

- Teacher John T. Scopes was arrested for teaching Darwin’s theory of evolution in Tennessee.

- A strike for higher wages at a Japanese-owned cotton mill in Shanghai resulted in the mill’s management committing brutalities against strike supporters.

- Hitler’s Mein Kampf was published.

- As many as 40,000 members of the Ku Klux Klan paraded in Washington, DC. The Klan had 5 million members, making it the largest fraternal organization in the United States.

- Immigration to the United States from Italy dropped by nearly 90 percent. Immigration from Britain dropped by 53 percent.

And the Spanish flu pandemic had ended just seven years prior.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Pope Pius was combating the sin of idolatry by refocusing the ultimate concern of the church on Jesus and his vexing ways of service, self-sacrifice, and subversive action. The power and wealth of the Vatican notwithstanding (the institutional church has always found a way to ignore its own privilege), he warned Christians against the trappings of empire and hoped that by identifying Christ as the opposite and celebrating him as king, the church and world might find their way to something more Christlike in character.

It may have been a good idea, but seeing the world now, it clearly did not work. At least in the United States, Christ the King has become a triumphalist and militaristic image of Americanity bearing no resemblance to the ethic of compassion envisioned in Matthew 25.

Because of this perversion, I, along with other church leaders, grumble about Christ the King Sunday every year. Can we just not do Christ the King Sunday? Can we skip over the Sunday where we feel compelled to proclaim Jesus as king but use our theological scalpels to detach him from everything associated with kingship and consumer culture like wealth, conquest, victory, supremacy, and nationalism? The grumbling about Christ the King Sunday has become as much a part of our script as the holiday itself, not unlike the annual Feast of Complaining about Commercialization that accompanies Christmas. You know, right before we all go out and buy stuff.

I have begun to imagine Christ the King Sunday as Christ the Center Sunday. The parallels we see between 1925 and 2020 are undeniable, right down to the arguments about the validity of science and the increase in White supremacist terror. I agree with Pope Pius that it is necessary to disentangle Jesus from the idols of our time, and in fact the idols of all times. But I’m not convinced the language of empire and kings is the way to do it. We need language and images that reject hierarchical constructs altogether while they compel us to a laser focus on Jesus, who he was, what he did, how he lived, and how he treated people.

Matthew 25 calls humanity to an ethic of decentering ourselves in the interest of meeting those in need with relief, compassion, comfort, and dignity. Centering and decentering are terms we hear a lot in conversations about power, discrimination, and racism. To be an antiracist in a racist society, it is the responsibility of those with power and privilege, those who live as the “centered set” of White culture, to practice decentering ourselves every opportunity we have. That sounds a lot like good old-fashioned discipleship—that is, a renunciation of sin as it was defined by Augustine and Luther, “to be turned or curved inward on oneself.”

Decentering is as important a spiritual discipline for White Christians right now as prayer and the study of scripture, and the three should often be practiced together. However, it is significant to note that, in Matthew 25, both the sheep and the goats are clueless in every way. It surprised them to know that whenever they encountered the hungry, thirsty, naked, stranger, sick, and imprisoned, they had, in the flesh, encountered Jesus, the Son of man. I receive this peculiarity as a caution against performative decentering, of being so self-conscious of one’s actions that being charitable, compassionate, or woke becomes yet another way of centering oneself in the eyes of God and others. See me being good? See me doing the right thing? See me giving this drink to someone? See me making it all about me?

As one curves outward, decenters, and self-sacrifices, the promised reward is an encounter with Jesus. It is unpredictable just when and how that may happen, but Matthew promises it is inevitable. This is the gospel of Immanuel, God with us, not as an abstract, distant king but as the ultimate living presence.