February 26, Ash Wednesday (Matthew 6:1–6, 16–21)

Every year, we repeat this dusty choreography.

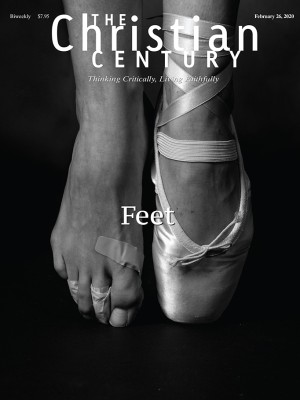

Prior to a ballet performance, I hold to a strict ritual of dusting my pointe shoes with rosin, a crystalized tree sap. A pointe shoe’s toe box is formed by layers of hardened glue and satin. This binds the foot, enabling the dancer to channel the strength of her ankles and feet to rise up onto the tips of her toes and balance there. But the toe box also makes the shoes quite slick, and rosin dust helps offset this.

The feat of elevation that pointe shoes provide gives the illusion of overcoming the earthly demands of gravity. Charles Didelot invented them in 1795 and called them “flying machines.” Marie Taglioni wowed audiences with her ethereal dancing in 1825, when she became the first ballerina to perform a role entirely en pointe in La Sylphide. While pointe shoe construction has evolved since then, rosin dust remains, and I apply it to my shoes as if my life depended on it. A shallow, plastic box of amber crystals of rosin hides in the wings on either side of the stage, ready to be crushed into friction-creating dust that keeps me from falling on my face.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

As rosin dust holds my feet fast, the dust of Ash Wednesday stops me in my tracks, disrupting my vertiginous illusions of grandeur, permanence, and indispensability. Every Ash Wednesday afternoon, I prepare for worship by mixing the dusty ashes of last year’s palm branches into the oil used for anointing. As the presider, I apply this dust to the foreheads of those gathered for worship, repeating this solemn truth to each person, “Remember you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

Every year, we repeat this dusty choreography—because the knowledge of our mortality slips from our minds again and again. These familiar moves, performed every first day of Lent, attempt to make the truth stick. This dust-formed cross confronts our desire to avoid facing the inevitability of death and the gravity of our humanity. Dust wins. Dust holds power over our plans, our personae, and our perceptions. The cross on our foreheads proclaims, “We are not God—we are dust.”

We then turn our attention to the coming 40 days of repentance. Our Gospel text from Matthew 6 lays out a three-step spiritual dance that can be adopted to keep us from slipping into self-centered ways. Personally, I slip and whirl through the intricate choreography of church administration, presiding and preaching, carpooling, mothering, spousing, friending, writing, volunteering, dancing . . . The 40 days of Lent invite me to slow down and step out of my self-centered turning.

Jesus says, “Fast, give, and pray.” These actions help God’s presence gain traction in our lives. We so easily slide into pride. We look to the world to bolster our egos. We clamor to be seen by others. We build bigger and bigger barns to house our worldly treasures, oblivious to the ephemeral nature of human life.

Spiritual practices beckon to us to experience the transient power of our dust in contrast to God’s eternal presence. The hunger pains of fasting force us in two directions: inward, as we assess how well or poorly we are feeding our bodies and souls, and outward, to see the bodies of hungry ones around us. Charitable giving calls us back to creation. We are reminded that our money, time, and talents are not ours; they belong to God. God calls us to steward them in gratitude and in service to our neighbors. Prayer quiets the incessant internal monologue of our minds and makes space for the stirrings of God.

Applying these practices to our lives helps us intentionally choose to store our treasures in heaven and not in dust. The ashes on our foreheads will wash away, but the wise application of fasting, giving, and praying can combat our human tendencies to greed, self-righteousness, and willpower that threaten our hold on the promises of God.

However, just as our dust cannot save us, neither can our spiritual practices. We slip out of our spiritual intentions. We sneak a piece of dark chocolate. We forget our daily devotions. We keep our money in our wallets. Next year, we will gather in worship again to be reminded we are dust. Is Ash Wednesday merely a Sisyphean task of morbidity, reminding us we are nothing and setting us up for failure?

One glance in the mirror at the dust on our foreheads says no. The dust is not smeared in grief and despair, covering our faces in ash. It is carefully placed in the shape of our salvation. The dusty cross on our foreheads hearkens back to the anointing of our baptisms, when a cross was drawn on our foreheads accompanied by the proclamation, “Child of God, you are sealed by the Holy Spirit and marked with the cross of Christ forever.” The promises of God stick to our dust and hold us in hope forever. That cross never leaves our lives; it is on our foreheads every moment of existence. The cross proclaims that every bit of our dust is claimed and loved by God. The dust makes apparent the promises of God that are bound to us. Our dust belongs to God, who can turn our ashes to beauty.

Safe dancing depends on dust, but thanks be to God our lives do not. The cross-shaped dust of Ash Wednesday serves to make the eternal promises of God visible. The grace that is bound to us by God is worth remembering every Ash Wednesday, and our dust dances in gratitude that God’s promises always stick.