Experience and maturity teach us that certain things in life cannot be forced. Love cannot be forced on another. The church’s liturgy does not inspire a soul through coercion. A child’s affection for broccoli can never grow out of threat and intimidation.

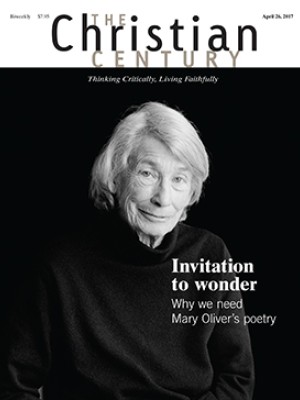

We might add poetry to the list (see “An invitation to wonder”). Years of reading poems to my wife in the morning have yet to win her over to the majesty of verse. Her cool reaction to what strikes me as a stimulating image or exciting metaphor suggests that the poems I choose sound roughly equivalent to a reading of the Congressional Record. So I choose my poems carefully and my poetry mornings sparingly, taking care not to confuse gentle persuasion with compulsion.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

A few weeks ago my wife and I attended a recital by a New York City opera singer. We both found the program transcendent, not simply because we know and love Claire, the singer, but because her glorious way of making music seemed to transport the entire audience to another world. The day itself was ordinary and gray. Most of us were sick and tired of yet another news cycle involving congressional probes into Russian interference with U.S. elections. A friend came over to us after the recital. “Wasn’t that spectacular? An hour and a half of poetry—something our country desperately needs right now. This is by far the best thing that has happened to me in 2017!”

We live and breathe more prose than we realize. These are not poetic times. The pace of our digital lives, the fear that overwhelms young and old, the vapidity of tweets, the punishing rhetoric about people we don’t care to know—these realities cut into poetic living. “What troubles me is a sense that so many things lovely and precious in our world seem to be dying out,” writes poet Galway Kinnell. “Perhaps poetry will be the canary in the mine shaft warning us of what’s to come.”

John F. Kennedy, whose inaugural was the first in U.S. history to include public recitation of a poem, championed the value of poets. In an address given at Amherst College, he said: “I look forward to an America which will not be afraid of grace and beauty . . . When power leads man toward arrogance, poetry reminds him of his limitations. When power narrows the area of man’s concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of his existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses.”

Poetry cleanses by telling the truth. At least good poetry does. It tells the truth through an economy of words, and by naming difficult and often inaccessible feelings. The late Jane Kenyon lifted up the artist’s task in this way: “The poet’s job is to tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth, in such a beautiful way that people cannot live without it.”

I might add that people cannot die without it either. A person who doesn’t have many hours or days to live needs every word to count. Talkativeness is blasphemy in such moments. But sacred hymns, with their beautiful and simple texts, can serve as balm to those nearing death. I’ve come to the conclusion that few graces compare with their poetry, which cleanses the soul and tells the truth.

A version of this article appears in the April 26 print edition under the title “In praise of poetry.”