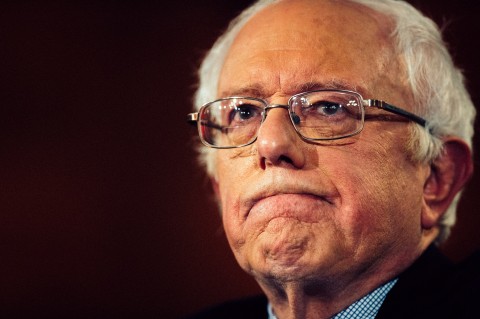

Was Bernie Sanders imposing a religious test for office?

The senator’s reasonable concern—that Muslims and people of all religions be treated equally—led to an unreasonable demand.

Senator Bernie Sanders (I., Vt.) turned a Senate confirmation hearing last month into an unexpected theological interrogation when he voiced concern that the nominee, an evangelical Christian, had declared Islam to have a “deficient theology.” Sanders was alarmed that Russell Vought, nominated to a post at the Office of Management and Budget, had once written that Muslims “do not know God because they have rejected Jesus Christ his Son, and they stand condemned.” Such a view of Islam, Sanders declared, was “indefensible,” “hateful,” “Islamophobic,” and “an insult to over a billion Muslims throughout the world.”

Vought replied that in those instances he had been merely stating his Christian beliefs. Sanders, later joined by Senator Chris Van Hollen (D., Md.), suggested that it was preferable to be the kind of Christian who does not view Muslims in those terms, and he concluded that he would not endorse for public office a person with such a negative assessment of Islam.

Sanders was rightly criticized afterward for being tone-deaf to evangelical Christianity and for coming close to imposing a religion test for public office. Although it is fair to ask candidates about their religious faith as it affects their duties in office, Sanders was mistaken to think that Vought had to abandon his fundamental beliefs in order to serve in government. Such a requirement is precisely what the constitutional guarantee of religious liberty is meant to prevent. (At the hearing, Vought eventually explained that his views of Islam did not mean he would discriminate against Muslims and that his Christian belief that each person bears the image of God would in fact lead him to treat everyone fairly.)

This unusual discussion in the Senate highlights one of the most challenging dimensions of interreligious encounters in a pluralistic democracy. The admirable effort to avoid exclusivist policies can easily become itself exclusive by setting up its own definitive judgment about what true religion is. Sanders in his own way was being as judgmental about religion as he thinks Vought is. For Sanders, it appears, the only approved religions are those willing to embrace other religions. His reasonable concern that Muslims and people of all religions be treated equally morphs into the unreasonable demand that religious people regard all religions as fundamentally the same.

Life in a religiously pluralistic democracy entails vigorous discussion of how we are to live together with our deepest beliefs, not without them. It calls us not only to learn to tolerate the deeply held convictions of others and learn about what those beliefs entail for them, but to recognize that, when it comes to fundamental convictions, there is no privileged neutral position: each of us is a strange “other” to someone else.

A version of this article appears in the July 19 print edition under the title “Inclusive or exclusive?”