The strange hope of dystopian fiction since The Road

Surviving and communing together are sacred gestures.

Nearly a decade ago, Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road arrived like a literary thunderclap. McCarthy’s vision was darkly sacramental: God is not absent, but God is most certainly distant and has left humans to their terrible devices. While McCarthy did not invent the dystopian genre, The Road expanded its reach and elevated its grandeur.

Civilization has disappeared, and a father and son roam together through a scarred world, witnessing “fires on the ridges and deranged chanting. The screams of the murdered. By day the dead impaled on spikes along the road.” As the duo struggles to survive, they also grieve the recent loss of their wife and mother.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It’s her memory that finally gives them a reason to go on. Hope, however fragile, comes in what McCarthy calls “some ancient anointing. . . . Where you’ve nothing else construct ceremonies out of the air and breathe upon them.” In his work, sacraments arise from the ashes of a charred earth and destruction becomes a form of creation.

In recent years, a new crop of novelists is engaging dystopian futures and creating lingering, encompassing visions. These novels are carving their own spaces. The future is bleak but well written.

In contrast to science fiction tales set in fantastical futures on distant planets, dystopian novels take the anxieties of people on earth and amplify them. Worried about the government tracking your web browsing? Imagine a world where surveillance is constant and crippling. Nervous about outbreaks of exotic diseases trickling into disparate pockets of America? Imagine a pandemic that reaches your doorstep. All dystopian novels need to do is carefully manipulate the current situation: our minds and hearts do the rest of the storytelling work.

Many recently published dystopian novels have hit the perfect storytelling tone while delivering their own brand of transcendent hope. Station Eleven, by Emily St. John Mandel, begins with a flu outbreak in the Republic of Georgia that explodes “like a neutron bomb” and extinguishes 99 percent of the world’s population.

The survivors drift, searching for gasoline and food. McDonalds and IHOPs become wayward homes. Weeds sprout from potholes and cracks in roads. Motel room doors hang open, and the occasional armed guard stands at a deserted gas station. The Traveling Symphony, a band of Shakespearean actors, breaks into abandoned houses to gaze longingly at televisions. They search for issues of TV Guide and books of poetry. They pine for the most mundane, drab effluvia of life before the pandemic—and realize those artifacts have now become sacred.

If the premise of a traveling troupe of actors existing in the shadow of a pandemic sounds absurd, remember that the apocalypse rewrites conventional rules. Entertainment is lifeblood in a devastated world. As one actor notes, “People want what was best about the world”—and that means scenes from King Lear.

Mandel’s novel also captures an essential truth: we need to experience joy, and we need each other. The symphony’s caravans have a line of text etched on their sides: Because survival is insufficient. Their world is desolate, but what “made it bearable were the friendships, of course, the camaraderie and the music and the Shakespeare, the moments of transcendent beauty and joy.” The churches are gone, but the divine is everywhere.

God is also on the tongue of a false prophet who arrives early in Mandel’s novel. After watching a performance, he claps as he moves toward the makeshift stage. Like any good huckster, he sees an opportunity. The prophet stands with the actors and says, “What a delight . . . What a marvelous spectacle.” He goes on, “We have been blessed . . . We are blessed most of all in being alive today. We must ask ourselves, ‘Why? Why were we spared?’”

The prophet asks the people to consider the perfection of the virus—how it succeeded in ways that previous influenzas did not. “I submit, my beloved people, that such a perfect agent of death could only be divine.” While the actors nervously wait, he continues: “I submit that we were saved . . . not only to bring the light, to spread the light, but to be the light. We were saved because we are the light. We are the pure.”

The prophet’s real intentions are more earthbound: he’s looking for a new bride, and he eyes the women in the troupe. This leader of a doomsday cult reveals an interesting trope in the dystopian universe: it’s not enough for the world to end. That plot element is too grand, too distant. The characters need an immediate, human foil. Catastrophe turns them inward.

In Zero K, Don DeLillo uses the fear of coming end times to explore the allure of cryogenics. As billionaire Ross Lockhart says, “Everybody wants to own the end of the world.” His wife, Artis, suffers from multiple sclerosis and other illnesses. Her body is fading away, and Ross seeks a method that will allow her body to “safely be permitted to reawaken.” Cryonic suspension is a god that’s real. “It’s true, it delivers.”

A lapsed Catholic, DeLillo imbues his sanitized future with sacramental cues and metaphors. The method’s name, Convergence, feels like something that might have been coined by Teilhard de Chardin. One of the group’s mantras is “Return to the earth, emerge from the earth.”

Ross’s son, Jeffrey, is skeptical. He wonders: “Do you think about the kind of world you’ll be returning to?” He has a point. The world of the present in Zero K feels blurry and nondescript. Most of the descriptions are of man-made places: large buildings, hallways, bedrooms, and quasi-futuristic structures. The Convergence facility feels like a movie set: more ornamentation than real place. The aching world that the aged are trying to escape feels like it is being burdened by terrorism and famine rather than by a single event. Video screens reel out horror scenes sans audio, as if they are implanting a nightmare in the minds of the viewers: “rain beating on terraced fields, long moments of nothing but rain, then people everywhere running, others helpless in small boats bouncing over rapids.” Later: “people wearing facemasks, hundreds moving at camera level . . . a woman seated on the roof of her car, head in hands, flames—the fire again—moving down the foothills in the near distance.”

When the world is being overtaken by rain and fire, the only way to escape is to step outside of time, and the Convergence offers the reprieve of cryonic suspension: “time compressed, time drawn tight, overlapping time, dayless, nightless, many doors, no windows.” DeLillo is able to tease some sentiment out of his characters’ march toward death: we weep with them in their desire to pause eternity and seek a form of resurrection. We understand that when the world people know is gone, they reach for familiar comforts.

Sometimes those comforts are domestic. In Edan Lepucki’s California, Frida and Cal are living in a shed in the woods of Northern California. They’ve fled the deteriorating streets of Los Angeles, with its shuttered stores, poverty, hunger, and murder—a place where “petty theft was as ubiquitous as the annoying gargle of leaf blowers had once been.”

The world beyond Los Angeles isn’t faring much better; there’s a devastating flu epidemic in the Northeast, and storms are ravaging other parts of the country. But Lepucki doesn’t give us long swaths of description about the outside world. The focus is on Frida’s desire to become pregnant. Cal thinks in masculine terms and imagines being out in the woods “cutting the umbilical cord with his Swiss army knife.” He knows that her concerns are different, however, and that she will want to leave their solitude and find others. “Families couldn’t exist in a vacuum.”

Cal and Frida have confined themselves to a four-mile area around their shed. Paranoid and protective, Cal wants to stay away from others—especially a group that is living in community nearby. But Frida’s pregnancy is the spur that gets them moving. As they near the commune they pass strategically placed, ominous monuments of junk and barbed wire.

Then California takes a number of twists. Frida finds her brother Micah, who she thought had died when he suicide-bombed a mall, living in the commune. But the mood is tense. Many in the community are congregated in what is called Church, which Micah assures the couple is not a religious group but a place of meeting and planning, a sort of community organization. But the group’s obvious metaphor reminds the reader that we’re compelled to seek order when the old structures have crumbled.

Frida is nervous about sharing news of her pregnancy with Micah. “Can you guys procreate?” she asks him, wondering if the women are infertile. When Cal lets the secret of his wife’s pregnancy slip out in a small group meeting, the novel’s mood shifts. The community members “believe in containment”; in order to stay in the group, new members must be affirmed by a communal vote. The pregnancy, although still a secret to most members, does not bode well for the couple’s acceptance.

No matter how far the characters travel, no matter how much the world has changed, their conflicts and anxieties return to the issues of family. When Frida’s pregnancy is revealed during the vote meeting, the couple is forced to flee. Now the state of the outside world becomes irrelevant. California suggests that dystopia leads to the resurrection of old, prosaic concerns: who is welcomed, and who is not.

For all of their dystopian structures, the dramas in The Road, Station Eleven, Zero K, and California turn inward. In order for a story to exist, characters need to dig up and out of the rubble and get on with what remains of their lives. Whether that means returning to entertainment or the bond of family, global concerns are inevitably cast aside and replaced with local conflicts. This is not to say that dystopian novels merely revert to domestic scenes; rather, the domestic scenes carry the weight of catastrophic loss. “All things of grace and beauty such that one holds them to one’s heart have a common provenance in pain,” writes Cormac McCarthy. He and other dystopian novelists reveal that the actions of surviving and communing together are sacred gestures. God might be hidden behind the smoke clouds and the rubble, but there’s a certain divinity in just moving, rebuilding, and rediscovering our old, necessary ways.

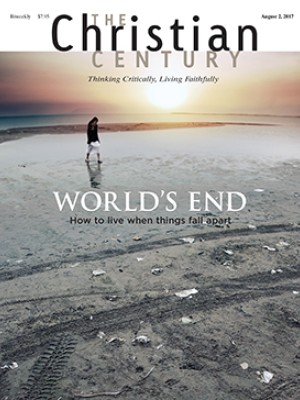

A version of this article appears in the August 2 print edition under the title “Survival is sacred.”