How can we fell the demons of hatred?

Narratives of fear, domination, and greed abound. But there's a better story.

Nazis on the march in America. We recoil at this news with a sense of shock, like getting a bad diagnosis. Our first instinct is denial. Could the social body really be this sick?

Naomi Klein, writing about Trump in a July issue of the Nation, said that we can’t really be shocked by where we find ourselves. “A state of shock,” she writes, “is produced when a story is ruptured, when we have no idea what is going on. But in so many ways, Trump is not a rupture at all, but rather the culmination—the logical end point—of a great many dangerous stories our culture has been telling for a long time. That greed is good. That the market rules. That money is what matters in life. That white men are better than the rest. That the natural world is there for us to pillage. That the vulnerable deserve their fate, and the 1 percent deserve their golden towers. . . . That we are surrounded by danger and should only look after our own. That there is no alternative to any of this.”

We breathe those toxic narratives daily, she says, so a Trump presidency is no real surprise. But it is a horror story. Night has fallen, and America’s demons have come out to play. The grotesque images of mindless anger at the neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville raise disturbing questions—about American society, certainly, but about human nature as well. How did those young men come to be so possessed by hatred and rage? Has the image of God been entirely erased from their twisted faces?

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Examining the rise of Nazism in his book The Coming of the Third Reich, Richard J. Evans saw desperate and resentful young men being attracted to extremism and violence “irrespective of ideology.” They weren’t looking for ideas, but meaning. They desired a cure for melancholy and malaise, a pick-me-up to restore a sense of personal significance. “Violence was like a drug for such men. . . . Often, they had only the haziest notion of what they were fighting for.”

Many found a sense of heightened self in “a life of almost incessantly violent activism, suffering beatings, stabbings and arrests.” Hostility to the enemy of the hour—communists, Jews, whomever—was the core of their commitment. As one young storm trooper later reflected on the bonding effect of collective violence, it was all “too wonderful and perhaps too hard to write about.”

Evans’s description provides clues to the pathology of white resentment and the resurgence of right-wing extremism. But explanations bring little comfort. And none of us remains a neutral observer, standing a safe distance from the fray. The demons are Legion, and we are all being swept along, however unwillingly, in the Gadarene rush to the cliffs of madness and destruction (cf. Mark 5:1–13).

Why is there evil? Where does it come from? The Creator spoke the world into existence and saw that it was good. But as the old stories tell it, the world’s goodness was soon complicated by a persistent power of negation, whose source remains something of a puzzle, though some say it is the diabolic urge to reject or destroy the gifts of life as a show of independence from the Giver.

Before he became Satan, Lucifer was one of heaven’s brightest stars. But his pique over being outshone by Christ precipitated his all-out war against God. His narcissistic self-assertion refused to bow to a greater reality, and he became the archetypal image of creaturely resentment. In the words of the 19th-century Russian writer Alexander Herzen, Lucifer is “the gloomy angel of darkness, on whose brow shines with dim lustre the star of bitter thought, full of inner discords which can never be harmonized.”

None of us is uncontaminated by this negation. At the end of his 2,000-page trilogy on the rise and fall of German Nazism, Evans concludes that “the Third Reich raises in the most acute form the possibilities and consequences of the human hatred and destructiveness that exist, even if only in a small way, within all of us. It demonstrates with terrible clarity the ultimate potential consequences of racism, militarism, and authoritarianism. It shows what can happen if some people are treated as less human than others. It poses in the most extreme possible form the moral dilemmas we all face at one time or another in our lives, of conformity or resistance, action or inaction in the particular situations with which we are confronted. That is why the Third Reich will not go away, but continues to command the attention of thinking people throughout the world long after it has passed into history.”

In The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky shows us this diabolical rage for destruction in the figure of Liza Khokhlakov, a sickly young woman once engaged to the saintly Alyosha Karamazov. Feeling herself in a world without God or grace, she dwells in the hell of lovelessness. “I don’t love anyone,” she insists to Alyosha. “Do you hear? Not a-ny-one.”

Dostoevsky gives this scene the title “A Little Demon,” and Liza seems possessed—and shamed—by an annihilating spirit. “I just don’t want to do good,” she says. “I want to do evil.”

Alyosha asks her, “Why do evil?” She answers: “So that there will be nothing left anywhere. Ah, how good it would be if there were nothing left! You know, Alyosha, I sometimes think about doing an awful lot of evil, all sorts of nasty things, and I’d be doing them on the sly for a long time, and suddenly everyone would find out. They would all surround me and point their fingers at me, and I would look at them all. That would be very pleasant. Why would it be so pleasant, Alyosha?”

Liza enjoys the fantasy of her self-loathing being confirmed by many accusers. But Alyosha refuses to take the bait. He simply responds without judgment, “Who knows? The need to smash something good, or, as you said, to set fire to something.”

Rowan Williams finds in Liza’s words the hellish despair of a morally indifferent universe, where there is just as much self-hatred as hatred of the “other.” If there is no God, then there is no redemption or release either, “and the sense of nausea and revulsion at the self’s passion for pain and destruction is beyond healing. . . . This is what Liza endures: to know the self’s fantasies of destruction or perversity and to feel there is no escape or absolution from them, to know that you are a part of a world that is irredeemable.”

Is there any exit from this ludicrous horror show? What word can we speak to fell the demons? Jesus? God? Love? Although such words have been misused at times for demonic purposes, at their purest they signify the beauty for which we were made, the true Form toward which all beings tend. They drive away the powers of negation and make our faces shine with the light of heaven. They set us free from the toxic narratives of hate, fear, domination, and greed and give us a better story, in which everything is gift and everyone is neighbor.

In his book on Dostoevsky, Rowan Williams cites Paul Evdokimov, an Orthodox theologian, who suggested that the saintly characters in Dostoevsky are like “the icon in the room, a ‘face on the wall,’ a presence that does not actively engage with other protagonists but is primarily a site of manifestation and illumination. Others define themselves around and in relation to this presence.”

I don’t know exactly what is being asked of God’s friends in places like Charlottesville, but I suspect it has something to do with embodying such a transformative and defining presence, with being “a site of manifestation and illumination” where others—maybe even some of those young haters—may rediscover their true Christlike faces.

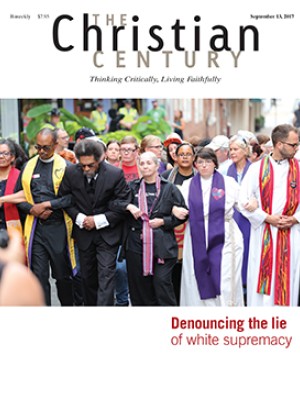

A version of this article appears in the September 13 print edition under the title “The demons have come out.”