James Cone's theology is easy to like and hard to live

If Jesus is black, he's calling us to do a lot more than affirm the color of his skin.

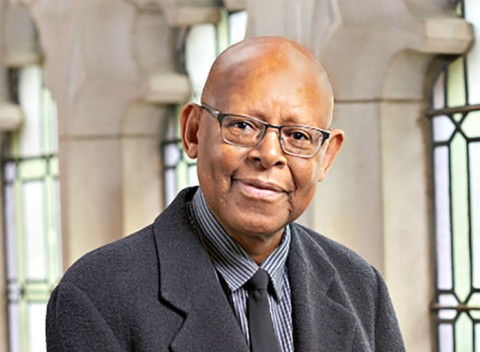

All theology starts with the particularity of the theologian’s experience, believed James Cone, who died Saturday at the age of 79. “I was born in Fordyce, Arkansas,” begins his groundbreaking work of black theology, God of the Oppressed. “Two important realities shaped my consciousness: the black Church experience and the sociopolitical significance of white people.”

These words were published in 1975. That same year, I was born in Geneva, New York, in a white middle-class family that went to church every Sunday. I grew up knowing nothing about the black church experience, and I was so immersed in the sociopolitical significance of white people that it never crossed my mind to think there was any other way of experiencing life in the United States. In other words, I’m exactly the kind of person with whom Cone was angry for much of his life. And I believe that his anger was justified. But my biggest sin, I’ve now come to realize, wasn’t the fact of my identity as a white person who grew up oblivious to my privilege. My biggest sin is that when I first read Cone’s writing in graduate school—and for years thereafter—I thought his theology was easy.

Though the founder of black theology, Cone was in some ways a traditional theologian, especially in wanting to affirm both the historical Jesus and the Christ of faith and hold them in a dialectical tension. In God of the Oppressed, Cone works through this tension by elaborating three statements: Jesus is who he was, Jesus is who he is, and Jesus is who he will be. Jesus was a Jewish man whose ministry was aimed at liberation of oppressed people 2000 years ago—and we encounter that same man today as the risen Lord who is present to us in our struggles. Not just any risen Lord, but one who is black. Christ comes into the world and takes on the quality of blackness (along with all of the oppression that blackness carries with it), countering the sin of racism by becoming one who suffers from it. But he is also black symbolically—and in that sense, he is present wherever there is human suffering.

Our encounter with Jesus Christ frees us from sin, death, and the devil. But it does so in a way that’s inherently political. It’s also eschatological. As the power of the historical Jesus irrupts into the present to bring a salvation that flows into political action, so does the power of the future Christ irrupt into the present, binding faith with action through hope. In other words, salvation has multiple dimensions. It works against the structures that oppress, particularly white supremacy in all of its forms. This reality doesn’t strip the crucifixion and resurrection of their power to save, but it redefines the meaning of salvation.

At the time, it was easy for me to articulate this theology in a classroom setting, and I remember being delighted years later when I had the chance to write about Cone’s Christology for one of my qualifying exams. “I’ll ace this one for sure,” I thought, and I did. I also had no trouble agreeing with much of Cone’s theology. I’d read enough liberation theology to be comfortable with its basic premises, to believe I could learn the most about God from people who had suffered far more oppression than I had, and to be able to live with some ambiguity in the relationship between salvation and liberation. I could easily concur with Cone’s statement:

There can be no reconciliation with God unless the hungry are fed, the sick are healed, and justice is given to the poor. The justified person is at once the sanctified person, one who knows that his or her freedom is inseparable from the liberation of the weak and the helpless.

As for the black Jesus, he felt to me no more foreign than a Palestinian Jewish man who walked around 2000 years ago. And I was comfortable with the idea that if we’re visualizing what Christ looks like in today’s world we should look at the people who are the poorest and most despised. In an article Cone wrote for the Christian Century six years after the publication of God of the Oppressed, he acknowledged that his initial theological emphasis on blackness failed to account for other forms of oppression. “Racism, sexism, classism, and imperialism are interrelated and thus cannot be separated,” he wrote. So if anything, Cone’s black Jesus may not be radical enough: perhaps the Jesus who shows up in today’s world is an unemployed black lesbian paraplegic woman. It’s easy for me to get on board with that kind of Jesus.

The problem is this: a Jesus who’s easy to understand and write about on exams is likely to be idolatrous if that Jesus doesn’t also change your way of life. For 20 years, I’ve known about Cone’s theology without asking myself what it means to live as if Christ were black, as if reconciliation with God were inextricably tied to liberation on this earth. I’ve believed that Jesus might be a suffering black woman without interrogating myself about my own complicity in the suffering of black women and men in today’s world. I’ve considered myself an ally without ever considering what I might be asked to give up if I were to engage in real advocacy. I’ve done more talking (and writing) than listening.

Cone’s theology isn’t all that hard to understand, and it’s not even that hard for a liberal mainline Protestant to agree with in today’s #BlackLivesMatter world. But Cone’s challenge to white Christians isn’t to get us to agree with his theology. It’s far more radical than that. As he puts it in God of the Oppressed, “God has chosen what is black in America to shame the whites. . . . The divine election of the oppressed means that black people are given the power of judgment over the high and mighty whites.” What Cone is calling for on the part of white Christians is much more difficult: sacrifice, the tearing down of our values, the relinquishment of the comfort that our sociopolitical significance affords us. He writes:

While divine reconciliation, for oppressed blacks, is connected with the joy of liberation from the controlling power of white people, for whites divine reconciliation is connected with God’s wrathful destruction of white values. Everything that white oppressors hold dear is now placed under the judgment of Jesus’ cross.

Nothing about this should be easy.

I wish that Cone were still around to keep writing and giving talks, to keep reminding me that understanding the outlines of a theologian’s perspective is far less meaningful than living in the way God intends for me. But Cone’s theology was never about himself, and I don’t need to look far to see Christ living in the bodies of those people in my city who are struggling the most. Maybe it’s time to put down God of the Oppressed and begin the much harder work of striving for justice.