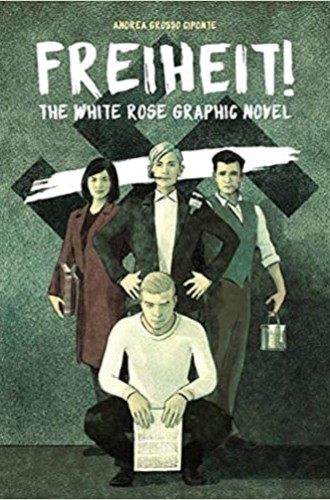

The White Rose movement in graphic novel form

Andrea Ciponte has found an ideal genre for telling the Scholl siblings’ story.

In 1942, a small group of German university students tried to wake up their country to the mass murder of Jews and other atrocities. “We will not be silent,” they wrote. “We are your bad conscience.” Brave with youth, they painted graffiti slogans like Down with Hitler! and Freiheit! (Freedom!) and left anonymous leaflets in public places. They called their nonviolent movement the White Rose, a name with poetic, philosophical, and religious echoes. The students managed to distribute only 15,000 copies of six leaflets before being arrested and executed. Yet their example inspired people all over the world. Soon after the members of the White Rose were killed, British Royal Air Force pilots dropped millions of copies of their sixth leaflet all over Germany.

This poignant story has been told before in film, theater, and opera. But it feels especially timely in this 112-page graphic novel.

“Every people deserves the regime it is willing to endure,” Andrea Grosso Ciponte’s story begins, citing the first leaflet. Ciponte is our troubled conscience. He wants us to grapple with how we have allowed another, more recent era of authoritarian cruelty.

He also wants us to celebrate the young people who lead resistance movements. Much like the young people who fill the streets today, members of the White Rose fill these pages, striking poses that older readers may remember from that age. Young men slouch, smoking pipes and affectedly quoting verse. Young women trail hands over lovers in German uniform, still trying on their adult personas. They are aware, not incorrectly, that they are blazing angels of truth.

Among them are the siblings Hans and Sophie Scholl, whose father has been arrested by the Gestapo for disparaging the Führer. Hans, a medical student, has already been publishing much more strident words in secret. He takes up the biggest guns he can fire from the classical German canon: Goethe, Heine, and Schiller, writers from an earlier era who speak to him, just as he may speak to us. (I do wish that Ciponte, who previously illustrated a biography of Martin Luther, also showed the strength that the Scholls draw from their Catholic faith.)

We meet Sophie on a train to Munich where she attends school, a free spirit in a police state. Part of what makes her such an appealing hero is that she has a rounded life and a future. She is carrying a picture of her fiancé, a bottle of wine, and a cake, unaware that it is to be her last birthday. Like Ciponte, she is an artist, although she says, “It doesn’t feel like a vocation to me. I think to be a true artist, you first have to become a whole person. You have to overcome your fears. That’s what I want most. To be a truly free person.”

When she discovers that Hans and his friends are behind the pamphlets, she volunteers for the riskiest jobs, distributing them surreptitiously in public places. In one beautiful series of panels, Sophie strides down a street while verses from Goethe ring in her head, ending with the exhortation Freiheit! Freiheit! Freiheit! With each step she grows larger and larger, until Hitler himself cowers under her shoe.

The story of the White Rose thrives in this form. A graphic novel is urgent. It combines the visual drama of film with narrative dimensions that film does not possess. Ciponte, a professor of film, shows himself a master of visual storytelling, moving us through a variety of panels painted in desaturated colors like faded photographs. We see characters from every angle, literally. Something or someone is always in motion—pamphlets tumbling, police chasing, people running from one page to the next. All this motion only emphasizes how confined the students are under the watchful eyes of police. Stifled interiors contrast with exteriors where people can breathe.

As in a well-cast movie, the characters convey their personalities before even uttering a word. The students in particular benefit from Ciponte’s observations, as a university professor, of how young people inhabit their bodies. Maybe 20-year-olds have always lounged and stretched like this, but these young men and women look utterly contemporary, and rightly so. As if to underscore the story’s relevance, a particularly misogynistic Nazi has been given the hard, bland face of a modern politician. He could be running for the US Senate.

Unfortunately, the dialogue is wooden. Ciponte hews closely to source documents and to German poetry, which was probably stiff even before translation. At one urgent moment, a character says, “The truth must ring out as clearly and audibly as possible in the German night.”

Then again, Sophie Scholl really did utter these heartbreaking last words: “Such a fine sunny day . . . and I have to go. What does my death matter, if through us thousands of people are awakened and stirred to action?” And a paper found in her cell really did include illuminated renderings of the word Freiheit.

One of the most valuable parts of this book is the appendix, in which all six leaflets are printed in full. They explode the notion that Germans did not know about the evil happening under their noses. A leaflet from 1942, three full years before the wider world saw the death camps, says this:

Since the conquest of Poland three hundred thousand Jews have been murdered in this country in the most bestial way. Here we see the most frightful crime against human dignity, a crime that is unparalleled in the whole of history. . . . Why do the German people behave so apathetically in the face of all these abominable crimes?

This appendix with its clarion prose speaks directly to the ineffectual citizens of an authoritarian state who may grumble but otherwise do precious little to obstruct evil. The White Rose puts a very urgent light on, say, Black Lives Matter.

In the end, this slender novel is itself like a pamphlet or graffiti, forceful rather than deep. That is to say, on its terms, it is completely successful.