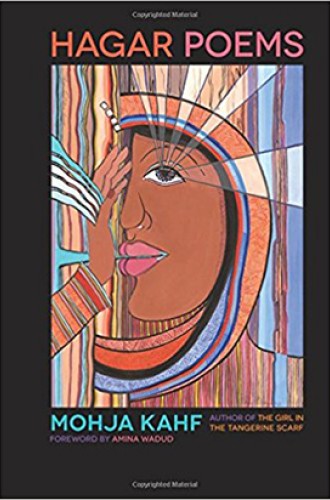

The prism of Mohja Kahf’s poetry

Kahf turns the stories of biblical and Qur'anic women to see their many facets.

I kissed this book when I finished reading it. That doesn’t happen every day. Mohja Kahf had just taken me on a rollicking tour of ancient texts and ancient women radiating through contemporary life that ends with a meditation on the “little mosque” near her home. I had been a companion to Aisha (one of the Prophet Muhammad’s wives) as she complained about her treatment in the tabloids and Zeleikha (Potiphar’s wife) as she went looking for Yusef in every man’s face and coming up empty. I’d considered Solomon from the distrusting perspective of the Queen of Sheba and met Miriam on the riverbank.

The trip had not been easy. Even as I felt that I was exploring some of my soul’s familiar territory, I had to keep Google close by. I did not know what the Kaba is or where Safa is or who the Midianites were. I had to go back and reread passages from Genesis and the Qur’an. Kahf’s poetry offers immersion in both the utterly foreign and the utterly familiar. If you like your poems straight, without the aid of Wikipedia, this collection could be frustrating. But situated within the borderlands of what I knew and what I didn’t, I found myself reading wholeheartedly.

The book is divided into three sections. The first section contains poems specifically related to Hagar, Sarah, Abraham, Ishmael, and Isaac—characters who appear both as archetypes and in narrative form. In one poem, Kahf imagines Hagar writing Sarah a letter of reconciliation, “What if we both ditched the old man?” The next poem, “Page Found Crumpled in the Wastebasket by Hajar’s Writing Desk,” takes a different tone to address the same painful personal history: “sarah you bitch / you backstabbing woman / trotting after your husband.” The story behind these poems is contained in a few brief chapters of Genesis with some interpretation and extrapolation in the Qur’an and the Talmud. But here it becomes a prism that the poet turns around and around as she tells stories about stories about stories.