The persecuted Assyrians, then and now

Thousands died, and many sacred places were destroyed—100 years before ISIS.

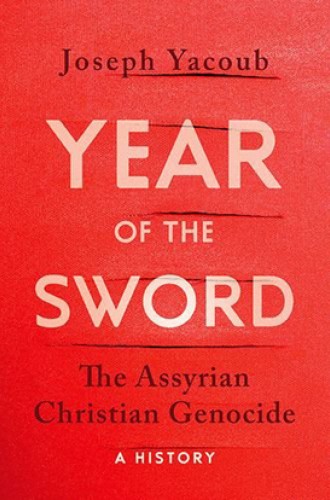

This meticulous and moving book was originally published in France in 2015, the 100th anniversary of the Armenian and Assyrian genocides—what Assyrians call “the Year of the Sword” (Seyfo). The Armenian genocide is well known. But despite ample documentation and eyewitness reports, the Assyrian genocide is much less known, partly because the Assyrians are often little known. Smaller in number than the Armenians, the Assyrians were widely dispersed, far from urban centers, and never had a state. An Assyrian document dated September 1, 1920, notes: “Battered and stricken nations like ours do not have enough men to have their voices heard.”

Assyrians—also called Chaldeans, Syriacs, Nestorians, or Jacobites—are descended from the early peoples of Mesopotamia with a history of perhaps 5,000 years. Most became Christian in the first century (through the mission of the apostle Thomas, their tradition claims), and they continue to speak Aramaic, the language Jesus spoke. They were sundered from many other churches over theological differences at the Councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon, and the majority became members of two churches: the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch and All of the East, and the Ancient Church of the East (often erroneously called “Nestorian”). Those who later came into communion with the Catholic Church are usually called Chaldean.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The Ancient Church of the East responded to Western rejection by becoming perhaps the greatest missionary church in history. Its operating languages were Syriac, Persian, Turkish, Sogdian, and Chinese. It established 250 dioceses and 1,000 monasteries from Iraq to India and China. It had bishops in Afghanistan, Arabia, China, India, Iran, Sri Lanka, Tibet, Turkestan, and Yemen. It may even have reached to Burma, Vietnam, Indonesia, Korea, Japan, and the Philippines. Later its numbers and reach were crushed, principally by Mongol conquests.

Joseph Yacoub estimates that at the outset of World War I, there were about 600,000 Assyrians in the Middle East. They often had peace and sometimes suffered persecution in the Ottoman Empire, especially in its later years. But in 1915, the goal was “to drive them out from geographical zones considered too politically sensitive by Turkish nationalists.” Consequently, “hundreds of thousands of people were massacred or died of thirst, hunger, poverty, exhaustion or illness on the road to exile or deportation.” Yacoub describes the massive scale of the genocide: “During the 1915 massacres more than 250,000 Assyrians of all different religious persuasions . . . died at the hands of Turks, Kurdish irregulars, and other ethnic groups.”

The massacres of Assyrians took place over a large area in what is now Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran—almost in the same places and the same ways as with the Armenians. In addition to the rape, torture, enslavement, and killings of people, historical monuments and artifacts were destroyed, churches profaned, and libraries of books and manuscripts vandalized and robbed.

Attacks continued, with massacres in 1918, 1924, and in Iraq in 1933. These were smaller but thousands were killed. After World War I, the British thought the Assyrians’ plight so grave that they considered moving them to Canada. In 1930, there were proposals to transfer them to South America. In 1933, the British flew the patriarch to Cyprus for safety while the League of Nations debated moving them to Brazil.

There was more death in the aftermath of the two Gulf wars. Then, just one year short of Sayfo’s centenary, ISIS began reenacting on Assyrians, Yazidis, and other minorities the same horrors as in 1915: rape, enslavement, killings, historical monuments and artifacts destroyed, religious sites profaned, and libraries of books and manuscripts vandalized and robbed. Yacoub writes: “There is no shortage of similarities between 1915 and 2015.” On March 17, 2016, the U.S. State Department and Congress classified ISIS assaults on Christians and Yazidis as genocide.

This fraught history has led to continuing emigration and flight. The Assyrians persecuted by ISIS “in Syria are the descendants of those who escaped the 1933 massacres in Iraq, themselves children of the Ottoman Empire’s victims in 1915.” One Iraqi Assyrian explained this to a “journalist from Le Monde in simple terms: ‘Our life is an exodus.’” Now the majority of Assyrians live far from their historic homeland. In 2003 in Iraq, Christians were some 4 percent of the population, but they have constituted 40 percent of those who have fled.

America is home to 500,000 Assyrians, with 100,000 in Chicago and a similar number in Detroit. These diaspora communities are growing, which leads Yacoub to end his compelling story on a note of hope: “Are we witnessing a historic turning point? As the exodus from historic Mesopotamia continues, the strength and self-confidence of the Western diaspora is conversely growing . . . [and] memory of 1915 is strengthening rather than fading. . . . This people may yet finally return to the stage of history.”

Assyrians may live fruitfully in the diaspora, and if they were to return to their lands they would find destroyed homes and livelihood in areas full of enemies. But we can hope for a fruitful return for some.

Fifteen years ago, I traveled in southeastern Turkey to Nisibis (now Nusaybin), which nurtured Ephrem, the great Syriac theologian and hymnographer. A church there dates from 439, but in 1915 it was abandoned when the Assyrian population fled into Syria. In recent decades, a Christian family from a local village lives in a small apartment in the church and tries to maintain it. We went into the crypt to see the tomb of Jacob of Nisibis, from whom the term Jacobite derives, and our Syriac driver began to sing an ancient hymn in a voice that filled the tomb. We asked him what the words meant, and he said that the lyrics came from Ephrem himself:

Listen, my chicks have flown,

left their nest, alarmed

By the eagle. Look,

where they hide in dread!

Bring them back in peace!