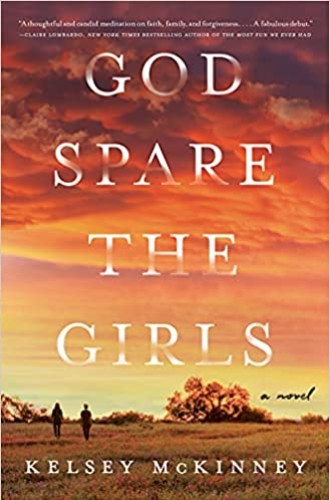

A novel about purity culture and its harm

At its core, God Spare the Girls is about a family history doomed to repeat itself.

Kelsey McKinney’s debut novel unravels the history of a prominent pastor’s family in Hope, Texas, offering insight into the inner workings of the sort of evangelical congregations that popularized the American purity culture movement. God Spare the Girls explores the potential of young womanhood—and in this community, its sudden dissipation—through the Nolan sisters, Caroline and Abigail, the summer before Abigail’s impending marriage. As McKinney peels back layers of family struggles that go back generations, she centers the sisters’ fight to grow closer and find comfort in each other during an escape to their grandmother’s ranch, while the consequences of their father’s sins swirl vastly around them.

As the novel begins, the Nolan family is working hard to maintain an immaculate image for the Hope congregation, while internally each individual feels a bit differently. Luke, an unusually famous evangelical preacher, has always gone to his eldest daughter, Abigail, for spiritual inspiration and advice. Ruthie, the mother, often confides in Abigail with her own personal struggles. Abigail has annually announced to Caroline that she wants them to be closer, but their sisterly bond has never seemed meant to be. Caroline is relatively isolated in her family, and as she begins to feel disillusioned with her faith she tentatively explores other ways of life, wondering whether she should follow the purity culture empire her father has helped build. By centering the evolving relationship between the sisters, McKinney gives insight into the particular type of life that young women in this community are prepared for by those around them.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

As the summer days on the ranch unfold, the Nolan sisters truly get to know each other for the first time. Abigail, an “old maid” at age 24, is more than ready to tie the knot with her fiancé, Matthew. She is the face of her father’s campaign against premarital sex that has gained him so much national attention, and she knows exactly what she wants in her life with Matthew. Caroline, on the other hand, has her doubts. She can’t quite imagine a future like her sister’s for herself, and she is unsure of who she would be without all of this structure in her life.

As Caroline and Abigail spend their days together in Nannie’s house, eating chips from Target and taking early morning walks together, Caroline is acutely aware of the “before marriage” timeline—when you get to be your own person, have your own last name, work at your own job, and do as you please. Once the countdown is over, she’s worried that she won’t recognize (or even like) her sister anymore. She’s seen it happen already with other young women in Hope who get married, have children, and then have so little for themselves. She looks at her mother and wonders if she’s happy with her life, and she becomes scared of losing the bond with Abigail that they have just barely formed.

Early in the novel, McKinney begins to hint that Luke is not as holy and godly as he would like his congregation and family to believe. When the Hope community learns that he has been lying about how he lives his life, the Nolans’ day-to-day existence spins out of control. As everyone but Luke is forced to atone for his sins, it becomes clear that he belongs on the list of powerful men in Christian institutions who escape the consequences of their worst actions. In the Hope community, there are many more men like Luke—and plenty worse. McKinnney makes it apparent that Luke isn’t rotting the church so much as bringing to light a rot that’s already there.

While Luke’s actions come as a shock to those immersed in his community, for many readers they call to mind the numerous abuses committed and covered up by Christian institutions and officials in the name of God.

When Caroline and Abigail become aware of Luke’s sins, they go to the church elders, thinking that if they are logical, calm, and well prepared, the elders will believe them. Instead, as Caroline puts it, “they had bathed themselves in God’s righteousness and holiness and it wasn’t enough.” The failure of Caroline and Abigail’s efforts evokes compassion for girls who grow up in environments like Hope, constantly second-guessing whether their actions are good and holy enough for God. It is disheartening to witness the sisters’ discovery that they will always be slightly disapproved of, simply because of who they are. In moments such as these, McKinney seems to gently question the sisters: Is this where your future is? Are these people who make you feel so alone really the ones who you want to invest the rest of your life in?

At its core, God Spare the Girls is about a family history doomed to repeat itself. Caroline’s perspective at Abigail’s wedding ceremony observes this cycle without doubt. Abigail “was the third generation of Nolan women to marry right here on this hill. Maybe the land really was cursed, Caroline thought.” As McKinney and her characters strip back the layers and continue to reveal each other, we get the sense that there is much that we will never know about the Nolans, and that every other family in the Hope congregation has their own timeline of secrets.

Caroline wants out. Abigail, however, is ready to play the game to get what she wants, which raises questions: Will her children eventually pay the price? What will it take to break the cycle of secrets and repression for the Nolans? The lesson that emerges is that just as no one individual is to blame for the harmful consequences of evangelical churches like this one, no individual woman is likely to take down that empire herself. Ultimately, every woman who grows up learning that she is not good, holy, or pure enough on her own deserves to find peace on her own terms. McKinney gives that chance to Caroline and Abigail—and to readers who see themselves in the Nolan sisters.