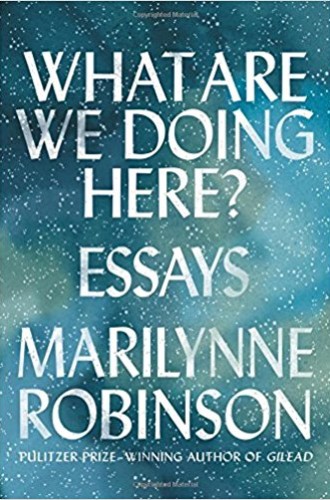

Marilynne Robinson's beautiful, cranky nonfiction

Robinson's essays are sometimes tedious. Yet they provide glimpses of the capacious faith undergirding her novels.

“I am too old to mince words,” Marilynne Robinson warns us in the preface to her fifth collection of essays. She wrote them between the spring of 2015 and the spring of 2017, mostly in response to lecture invitations from American universities, and they speak frankly, at times polemically, to Robinson’s sense of the current American historical and political moment.

The “we” in her title is primarily her fellow citizens, beneficiaries of American democratic traditions and their embodiment in religious, political, and educational institutions. “Democracy,” she acknowledges, “is my aesthetics and more or less my religion.” What gives these essays an often wistful and sometimes combative tone is Robinson’s sense that this democratic heritage is under threat.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The essays were written during a sea change in American politics—the end of Barack Obama’s presidency and the beginning of Donald Trump’s—and they leave no doubt about Robinson’s political leanings. “A Proof, a Test, an Instruction” is a lyrical ode to Obama written a month after Trump’s election, while “Slander” is a mournful and enraged homily about her mother’s end-of-life addiction to Fox News.

Obama read Robinson’s novel Gilead while on the campaign trail in Iowa, and during his years in the White House they struck up a friendship. He embodies what she sees as quintessential American virtues: a dignified civility, a drive to democratize privilege, an embrace of our nation’s heterogeneous union. “We see ourselves in him,” she writes, “and in him we embrace or reject what we are.” By contrast, Fox News embodies for Robinson the betrayal of that proud heritage, with its scorn for the vulnerable, its fiction of a threatened and embattled Christianity, and its nostalgia for an American past that never was.

Robinson is best known for her prize-winning novels, starting with Housekeeping in 1980, and then, after a decades-long gap, her trilogy Gilead, Home, and Lila. Her finely etched characters draw us into ordinary human struggles with family and friendship, love and death. In the essay “Grace and Beauty,” Robinson muses on what she has learned from years of writing fiction and teaching others how to write it. To have their own integrity, fictional characters must exhibit both consistency and freedom. Credible characters take on a life of their own. An author should not use them “to represent a type or to make a point.”

Alas, in her essays Robinson often uses characters from history or caricatures of behavioral science to do exactly that. The didacticism and moralizing she eschews in her novels frequently take center stage. She ranges confidently across theology, economics, physics, history, and anthropology. She delivers sweeping indictments of entire scholarly fields: “American historians have inflicted grievous harm on American history” and “the modern science of the mind is to science in general as a blighted twin is to a living body.” Considerable repetition across the essays means that readers become well acquainted with Robinson’s intellectual hobbyhorses: her strange admiration for Oliver Cromwell, her praise for the civic virtues of New England Puritans, her disdain for reductionist theories of human life.

Robinson’s essays are no substitute for her novels. They sometimes make for tedious or exasperating reading. Yet, at their best, her essays provide glimpses of the capacious Christian faith undergirding her novels. Contemporary writers of fiction often avoid religion for fear of appearing sectarian or exclusivist. Robinson is an exception. She finds that only a theistic universe is a large enough canvas for portraying the flawed beauty of human life and the mysterious depths of human experience. She writes theological novels in order to do justice to the complexity of the world as she finds it. Robinson’s essays give readers a window on the generous Christian humanism animating her theological worldview.

Her Christian faith leaves her open to the vast mystery of being “intrigued and comforted by the thought of everything we do not know.” She finds God’s world shot through with beauty, a power that both compels and rewards our attention. Her faith affirms the intellectual drive to understand ourselves and the world around us. Robinson has no patience for a narrow, defensive Christianity that desperately battles the claims of modern science by clinging to scripture as “a collection of just-so stories.” Her faith is not threatened by the presence of religious others but instead embraces a universalism “that precludes any notion of proselytizing.” For Robinson, earthly human life is a splendid gift of God’s grace. “We have untried capacities to live richly in a universe of unfathomable interest, and we can and do, amazingly, enhance its interest with the things we make.” This conviction funds Robinson’s advocacy for democratic institutions that provide spaces for human excellence to flourish, especially schools and universities.

In these essays, Robinson calls her fellow Christians to be public theologians, celebrating beauty, upholding “the humane, heroic openness” of civic institutions, and cultivating the communal virtues of respect and truthfulness. “It behooves Christians to think and act like Christians.” She has set a wonderful example for the rest of us to follow.