Laughing at what’s not funny

Like Jason Micheli, I have incurable cancer. His book helped me find humor in it.

This book arrived at my doorstep the day after a friend of mine died of pancreatic cancer—the third friend in six months to die of the disease. What a laugh, that cancer.

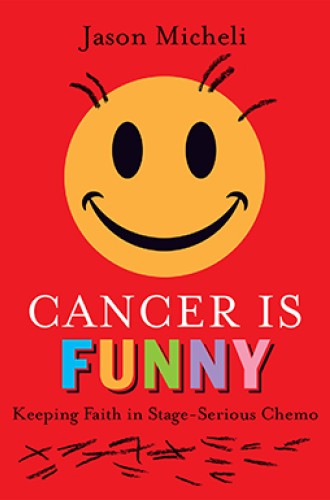

My husband winced involuntarily when he caught a glimpse of the title printed in multicolored letters just below a big smiley face emoji with its hair falling out. In our ninth year of communally living with my very own version of stage-serious, incurable cancer, it felt more than a little sacrilegious to have this emoji and that sentiment adorning my bedside table.

This may help explain why, when I cracked open Cancer Is Funny, I wasn’t smiling.