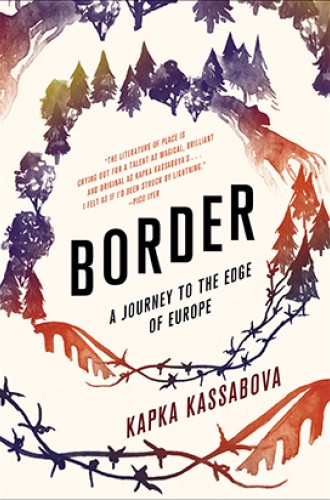

Kapka Kassabova returns to Bulgaria

A travel writer's visit to the borderlands of her childhood

Reading Kapka Kassabova’s new book is something like that moment of startling awake just before you fall asleep. There’s the relief of knowing you’re safe and far from danger. But there’s also a lingering disorientation, even a vague dread.

The eponymous border is “the last border of Europe . . . where Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey converge and diverge . . . where something like Europe begins and something else ends which isn’t quite Asia.” It’s a liminal, neither-here-nor-there region that has fascinated Kassabova since her childhood in Soviet Bulgaria.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The journey she chronicles in the book was born of a desire to see what had been kept from her by the barbed wire and the soldiers waiting to catch those who got too close to the edge. “I wanted to see the forbidden places of my childhood,” she writes, “the once-militarized border villages and towns, rivers and forests that had been out of bounds for two generations. I went with my revolt . . . and with my curiosity.” Her adult excursion into the mostly demilitarized woods retains a feeling of subversiveness and wonder that only a childhood’s worth of curiosity and fear could provide.

Kassabova is a poet, travel writer, and memoirist who has won awards and accolades both in New Zealand, where she landed with her family as a teenager, and in Scotland, where she now resides. Every ounce of skill and talent she has gathered along the way is on display here. The result is an ethereal siren’s song woven from the myths, legends, and languages that converge in the borderland.

The lure works. The reader is hypnotized by lush descriptions of the region. Lively portraits of its residents both distract from and highlight the atrocities that were periodically inspired by proximity to the dividing line—until Kassabova allows the region’s ghosts to catch up.

Kassabova’s journey begins in Strandja, a forested mountain region along the Turkish-Bulgarian border that teems with Tertiary-era lizards and with stories about a blind prophetess who told of the hidden tomb of an Egyptian goddess and a celestial fireball that may or may not be a zmey, a dragon. Strandja is also home to equally ancient horrors, however, and Kassabova never allows the reader to forget it.

Also living in these woods are former members of the brutal border patrol Kassabova was raised to fear, as well as the victims of the border patrol’s cruelty. These residents carry memories of bullets shot and dodged, identities and freedoms stolen and protected at all costs. For all the sins laid bare in these pages, the scars of the losses and trauma endured by the border’s residents are equally visible. So are the fears and desperation that motivated their actions. These memories may contribute to the darkness that permeates Strandja. That their owners never lose their humanity is a testament to Kassabova’s empathy and skill as a writer.

If the sinners in this book are hard to convict, its saints are equally hard to pin down. As Kassabova winds her way through Greece and Turkey, the reader is introduced to displaced persons of every stripe: ex-Soviet citizens who made it through the Iron Curtain, Syrian refugees, and ethnic Turks deported from Bulgaria in 1989. Kassabova finds these people gathering at cafes, restaurants, and apartments, waiting for news, for relief, for their new residences to feel like home. While these people are victims of circumstance, Kassabova doesn’t pity them or allow them to become symbols of others’ cruelty. She grants them full, complex humanity, allowing them to speak for themselves in a way most books about refugees do not. These, too, are people the reader can identify with but cannot easily idealize—a breath of fresh air in an era of ideological extremes.

This egalitarianism is probably the most political element of what could’ve easily been a very partisan book. The people Kassabova describes are literally on both sides of the line, but their stories are united by themes of loss, fear, and a longing for home, either extant or long gone.

Among the ideas Kassabova introduces between chapters is Mircea Eliade’s myth of the eternal return, an assertion that rituals connect people to a sacred, eternal time separate from the contemporary world. She sees her return to Bulgaria—both in general and at the end of the book—as a reconnection with that eternal time-outside-of-time. But the bearers of the human story Kassabova sets out to tell share experiences that are both eternal and uniquely modern. The result is a portrait of a place out of time, separate from the countries the speakers inhabit—a distinctive space that the reader can enter too after falling under Kassabova’s spell.

Reading Border is a dizzying reminder of the common humanity found on either side of any border. I, for one, still have vertigo.