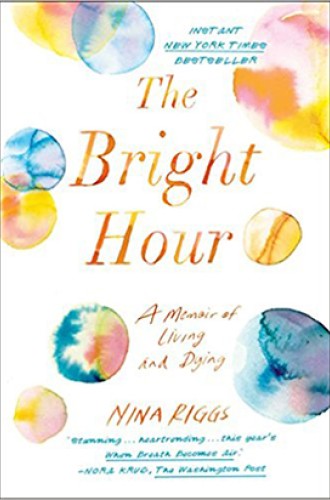

Dying—and living—with breast cancer

Nina Riggs's love of the world shines through her memoir, even as the ground shifts beneath her.

Ancient Egyptians brought skeletons to their feasts, exhorting guests to drink and make merry while they still could. American Puritans in the 17th century kept skulls as warnings to sober up and focus on the afterlife. Memento mori, the gruesome reminders were called: remember that you must die. People died suddenly, and young. They wanted to be prepared.

Nina Riggs did not feel prepared when she learned that a small spot in her breast was malignant. Cancer ran in her family: it had taken three grandparents and several aunts, and her mother was in treatment for multiple myeloma. But Riggs was only 37. Her sons, Freddy and Benny, were eight and five; she was not ready to leave them. Merrymaking had its place, but it didn’t address her concerns. And the afterlife, if it existed, was unknowable.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

So Riggs, a published poet, turned to writing as a way to shape and contain her experience: first an online journal, Suspicious Country, initially to keep friends and family informed; then an essay in the “Modern Love” section of the New York Times; and finally, during the last six months of her heartbreakingly short life, this memoir, her memento mori for 21st-century readers. “I see the young mother’s double take, the kids who stare, the waiter’s nervous glance, my friends who jump to adjust my chair,” she wrote late in her illness, after a lunch out. “Maybe the skeleton at the feast is me.”

Unlike skulls and skeletons, however, Riggs is neither spooky nor gloomy. Her book’s title comes from a journal entry by Ralph Waldo Emerson—her great-great-great grandfather—in which he praises morning, a “moist, warm, glittering, budding and melodious” time when one can “cease for a bright hour to be a prisoner of this sickly body” and “become as large as the World.” Riggs’s love of the world shines through every chapter, even as the ground shifts beneath her. A second tumor is discovered; a mastectomy is advised. Her husband, John, says he can’t wait for things to get back to normal. She cuts him short. “I have to love these days in the same way I love any other,” she protests. “There might not be a ‘normal’ from here on out.”

So she wallpapers the mudroom, installs a fire pit in the backyard, assembles a rocking chair, and plants a garden. “Please stop,” John pleads. So she stays up late reading, parties with friends, surprises John with a trip to Paris, and takes the boys to Orlando. Just days before what will be her final trip to the hospital, she is sitting on her deck watching her sons at play. She feels the light on her skin. “We love the days,” she writes. “They are promises. They are the only way to walk from one night to the other.”

Make no mistake: this is no feel-good book, no chirpy assurance that we can magically rise above the infirmities of the flesh until we shuffle off this mortal coil. Riggs must deal with her young son’s diabetes and her mother’s final illness as well as her own grief, terror, and pain. Some days her back, riddled with tumors, hurts so badly that she can’t get out of bed. But Riggs, a master of metaphor, usually describes her struggles indirectly. Instead of detailing her symptoms and treatments, she lists her mother’s. Instead of discussing her anxiety, she describes “the packed room of anxious women ranging from twenty to ninety all in our identical gray dressing gowns.” In a bleakly gorgeous account of scattering her mother’s ashes, she lets a bereaved guinea hen—“the last living member of [her] species at the end of summer on an island in the chilly Atlantic”—convey her own intense grief: “There is no fear as great as her fear. From time to time she lets loose a great squawk, . . . a desperate hollow call out into a world where the wind blows and the sun shines and children and dogs run in the lawn but where there is no one that matters to answer.”

Riggs often lightens painful scenes with wryly humorous observations—the MRI machine that sounds like a punk band of hostile aliens, the chemo-destroyed pubic hair that looks like “a drowned baby muskrat in the drain,” the breast surgeon’s office “tucked back among perfectly perky B-cup-size rolling hills.” Especially delightful are the cautionary emails her friend Ginny, also living with stage four cancer, imagines sending her future teenaged children from the grave.

Still, I probably wouldn’t give The Bright Hour to a person living with cancer. Riggs is writing for the rest of us: those who rarely think about death because, at the moment, we feel fine. “A bus. A cough. A rusty nail,” she intones. “Death sits near each one of us at every turn. Sometimes we are too aware, but mostly we push it away. Sometimes it looks exactly like life.” One sunny morning Riggs and her husband are running alongside their six-year-old son, teaching him to ride his bike. She trips and falls. Her spine snaps. Two days later the ER doctor tells her that the cancer has metastasized. In 14 months, she will be dead.

“Living with a terminal disease is like walking on a tightrope over an insanely scary abyss,” she writes. But “living without disease is also like walking on a tightrope over an insanely scary abyss, only with some fog or cloud cover obscuring the depths a bit more—sometimes the wind blowing it off a little, sometimes a nice dense cover.” Remember that you will die.

Riggs was not conventionally religious. “Faith is a word I have struggled with,” she admits. “For me, faith involves staring into the abyss, seeing that it is dark and full of the unknown—and being okay with that.” Meanwhile, “there is life—this bright hour.”