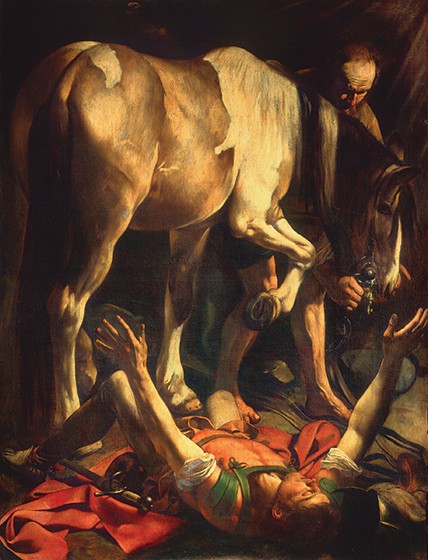

The Conversion of Saint Paul, by Caravaggio

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610) painted The Conversion of St. Paul to be paired with Crucifixion of St. Peter and to establish a theme of suffering in the private chapel of Monsignor Tiberio Cerasi, treasurer general under Pope Clement VIII, in Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome. Caravaggio does not embellish the narrative with reference to an apparition of God or angels (Acts 9:1–6, 22:5–11, 26:13). The psychological dimension is very modern: Saul, the persecutor of Christians, is knocked flat on his back before the viewers’ eyes and almost into their space. He is converted through the penetrating light of God—“a light from heaven flashed about him” (Acts 9:3). He does not react in fear but opens his arms to receive as much of the light as possible. His eyes are closed to indicate the blindness that he endures for three days. His commission to be the apostle of the gentiles is symbolized by Caravaggio’s depiction of him in Roman garb. The presence of the horse, while missing in the biblical text, is a common feature in visual depictions of the event, underscoring his standing as a Roman patrician and explaining how he “fell to the ground” (Acts 9:4).