Encountering the sacred Black feminine

“God’s social location is nowhere near women or Black people. I had to start looking for an image of the Divine that can speak to that.”

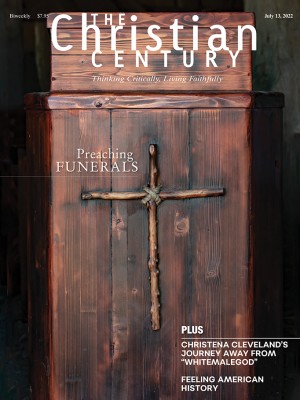

Christena Cleveland is a social psychologist, public theologian, founder and director of the Center for Justice + Renewal, and author of God Is a Black Woman. Cassidy Hall spoke to Cleveland for her podcast Contemplating Now, where a longer version of this conversation can be found.

In God Is a Black Woman, you remind the reader that Christian mystics throughout the centuries have savored the feminine in Christ and affirmed the divine mother working within the person of Jesus Christ. Is it possible for us to get back to those roots in a world doused with White supremacy and patriarchy?

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It’s a challenge. The world was simpler for medieval mystics. The trappings of capitalism—which I think is an excellent partner to White supremacy and patriarchy—were not as available to everyone. If you were a low-level monk or nun, access to power was not even a possibility. People looked for power in other ways, such as connection with the Divine—power with rather than power over.

Now, especially in the United States, there are so many carrots that capitalism, White supremacy, patriarchy, and the whitemalegod are putting out there to lure us into their folds, and the church is incredibly complicit in them. So there’s a level of subversion, of anarchy against the system, that’s necessary. It’s worth noting that many of those early mystics ended up getting excommunicated or killed because of their radical approach to the Divine. For us today, it’s probably more along the lines of social exclusion and, frankly, not having the language to do it.

Do you see those mystics—and even modern-day mystics—as activists as well?

Because so much of the way that mysticism is understood in the United States is White, I hesitate to connect mysticism with activism without a huge asterisk. The vast majority of people who call themselves mystics, I would say, are really just trying to help White people connect with some sense of peace. They’re not working against the systems of capitalism that keep people working 80 hours a week just to put food on their table. They’re not working for any of the things that would create some time and space for other people to connect with mysticism.

I went on a pilgrimage to Ávila to study Teresa of Ávila. I remember at the end of the retreat telling the teacher, “OK, so Teresa went into this castle and got closer to the Divine, but she was still proslavery and antisemitic.” There needs to be something more than just these inner pathways to the Divine in order to call it activism. Certainly, Teresa was reforming some things within the church, but only the things that were relevant to her and her body. It wasn’t intersectional.

You walked 400 miles across Europe, to the ancient shrines of Black Madonnas, where you found a special connection with one of them, Our Lady of the Good Death.

Raised in a Christian home and in academia, I was really attached to linearity, consensus, tradition, and some of the more patriarchal ways of knowing. Those are not invalid ways of knowing, but I was trapped in that certainty. I came to realize that some of my questions about my experience as a Black woman in the world could not be answered with those ways of knowing.

So I was really grateful to connect with this particular Black Madonna, who helps us die to some of the trappings of White patriarchy that hold us back. She’s called Our Lady of the Good Death because she stands at the dividing line between life and death and promises us that if we die to some of these identities and these attachments, she will help us find our true self. She’s unique, because only a small percentage of the 450 Black Madonnas in the world look explicitly Black or have what we would call African features. Many of them have black skin combined with more Eurocentric features. It was powerful to really encounter someone who looks like they could have been my ancestor. The Black Madonna and the divine feminine in general invite us past certainty and into uncertainty.

What was your impetus to go seek the Black Madonnas?

When Trayvon Martin was killed, there was a clear divide between the Black and White people in my life. The White people were not listening to this national conversation that Black people were having. I started to connect the dots with this White Jesus that I had been exposed to, both in Black church spaces and White ones. Not only is that historically inaccurate, but it says something about God’s social location, who God cares about, who God stands with and relates to.

But it wasn’t until 2016, in the run-up to Trump’s election, that I started to look at Jesus’ exclusively male gender. I wasn’t surprised when Christianity, broadly speaking, did not denounce Trump’s racist and xenophobic comments. My response was, Oh yeah, I know they’re racist. I’ve been dealing with the church and Christian institutions my whole life.

But people in the church take White femininity so seriously. When Trump started talking about assaulting White women, I thought, Surely Christians are going to defend them. When they didn’t, I realized that the problem is not just White Jesus, it’s male Jesus. God’s social location is nowhere near women or Black people and other people of color. I had to start looking for an image of the Divine that can speak to that. That sent me on my hunt, and I found the Black Madonna, who’s a Black, female, sacred, ancient image of God.

There are about 450 official Black Madonnas around the world. To be an official Black Madonna just means that you have some sort of connection to the earth in your lineage or your story, you have miracles associated with you, and you’re in some sense Black. France has more Black Madonnas than any other country. Spain, Germany, and Italy have a lot too. A lot of this has to do with the Moor influence in Southern Europe. The part of France where I did my pilgrimage was occupied by the Moors for 800 years. So some of the Black Madonnas are Black because the Moors brought them.

Some of them, though, are Black because they’re made from black materials. Our Lady of the Good Death is actually made of black lava rock because that entire region is a chain of volcanic mountains. And then there are a few of them that have been blackened over time. Every once in a while you see one of these Black Madonnas being “restored”—returned to her original color, which means White. There’s a lot of controversy around this because they’ve been known for a thousand years as Black.

Drawing us to the divine Black feminine does something different than drawing us to the Blackness of Christ. Were you influenced by others’ work on the Black Christ?

I remember watching a James Cone speech where he said, “Everything I do is for the liberation of Black people.” I stopped and thought, Nothing I do is for the liberation of Black people. I’m out here doing “reconciliation work,” but it’s for the enlightenment of White people. I don’t think I would be where I am without liberation theology, including Korean feminist liberation theology, Latinx liberation theology, and the Palestinian theologians. Without them, I don’t think I would have even known that I get to have my own perspective on scripture.

That said, I do think there’s an additional layer that I’m adding by bringing in the femininity of God. Much of liberation theology happens outside the academy. Mujerista theology is really just Latinx women living their lives. Womanist theology is really just Black women living their lives. But unfortunately, those conversations have been owned by the academy. What’s really powerful about divine feminine theology is that it is inherently grounded in the woods and in conversations.

Divine feminine theology is equalizing because anyone who has a body can have a theology. That gives voice to a lot more people. But it’s also scary because the patriarchy can’t control it. If I have a body, and you have a body, and everybody has a body, then we all have access to truth, and patriarchy can’t just say, “This is the truth.”

In your book, you write about the power of contemplative walking, combined with mindfulness and academic research. Does the research ever get in the way of the embodied approach?

It’s always been a struggle for me to allow my body wisdom to come to the forefront. On my pilgrimage, I actually didn’t do any research on the Black Madonnas before I went to visit them. I allowed the way they looked and what was going on around them to speak into my experience of them. Then, afterward, I read about origin stories and miracles that were associated with them. That was really helpful.

The challenge of telling my story forced me to be in my body because I’m really not a narrative prose person. I felt underprepared and under-resourced for creative writing. I dealt with that by going for walks in the morning. I’d get up at five, walk until 10 or 11, and just spend time in my body. Then, in the afternoon, I’d get to writing. My contemplative walking muscle got stronger and stronger and became a partner to my academic acumen.

I feel robbed, actually, by my academic training because I learned early on in my contemplative journey that this is where my soul wants to be—in my body, not just in my head. It feels like home in a way that academia never has. I’m sad that it took me 30 years to find it.

Your book includes photos of many of these Black Madonnas, which allows us to go there with you. How would you recommend people who can’t see these Black Madonnas in person get in touch with this kind of mystical unknown in everyday life?

Well, to quote Kelly Brown Douglas, “Christ is a Black woman anytime Black women are working for the liberation of their communities.” I think that can be true for any race. For Black women who want to encounter the sacred Black feminine, I say, look around to the Black women in your lives.

But I think what my book is really about is finding ourselves in the Divine. For me that meant encountering the sacred Black feminine, and I want everyone to encounter the sacred Black feminine because I think it will heal our spiritual imagination. But I also want everyone to find the sacred whatever they are. Because that will also heal our spiritual imagination. Because White Christ hasn’t done that for White people. If White people actually felt sacred, the world would be a different place.