The World Council of Churches in wartime

The grim future of communion with the Russian Orthodox Church

Ecumenism, the goal of visible unity among the world’s Christians, seems ever more elusive in our fragmented and fragmenting world. The barriers to a putative “common faith” involve a long-standing intra-Christian debate: How should the faithful relate to modernity and the general posture of cultural liberalism that has come with it? Supporters of the ecumenical movement that birthed the World Council of Churches in 1948 have generally taken a comparatively positive view of modernity and cultural change; many member churches, for instance, ordain women and officiate weddings for same-sex couples.

Such questions of culture and sexual ethics are important in their own right. Often, however, they are engaged as proxies for other conflicts.

A recent example involves Patriarch Kirill of the Russian Orthodox Church and his justification of Russia’s attack on Ukraine as a kind of holy war against the infiltrating decadence of the West, a decadence evinced, he claims, by pride parades that took place in the Donbas region prior to the pandemic. There is a struggle for the soul of the Eastern churches that, by Kirill’s reckoning, constitutes a metaphysical battle. Russia is bound by God, he insists, to win this battle. A truer story, of course, would account for Russian president Vladimir Putin’s attempt to regain geopolitical dominance—and for the ROC’s attempt to claim a portion of the Putin regime’s power.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Leaders of other communions are increasingly prepared to name Kirill’s efforts to baptize an unjust war as jingoistic and unchristian. Some, including former archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, have gone so far as to say that this warrants the ROC’s removal from the WCC. Complicating things is the reality that the ROC is the largest single church officially represented in the WCC. Its nearly 114 million members make up roughly a quarter of the council’s total constituency.

All this will come to a head on August 31 when the WCC’s 11th global assembly begins in Karlsruhe, Germany. There are no easy answers as to how to proceed. The WCC can continue to allow the ROC its membership—a de facto legitimation of Kirill’s spiritual authority even as he makes his church lackey to a murderous autocrat. Or it can expel the church—and thus reinforce Kirill’s antagonistic narrative that the liberalism of Western Christians is antithetical to Orthodoxy itself, thereby deepening the divide within that tradition in a way that empowers ultraconservative isolationists. This divide is already punctuated by the fact that the outgoing general secretary of the WCC is Ioan Sauca, a Romanian Orthodox priest who is amicable to the West.

If there was a glimmer of hope in this situation, it has been all but extinguished in recent weeks. That glimmer emanated from within the Russian Orthodox delegation to the general assembly. As of early June, that delegation was set to be headed by Metropolitan Hilarion (Alfeyev), the religious leader who was recently removed from his position as head of the Moscow Patriarchate’s Department of External Relations—the main ecumenical body of the ROC—and from the permanent seat on the main ROC governing body that came with it. Hilarion, just 55, had held that post since 2009. His immediate predecessor was the future Patriarch Kirill, and before Hilarion was deposed it was widely assumed that he was being groomed to succeed Kirill as patriarch.

The Oxford-trained Hilarion has been called a polymath. He has been published more than 600 times and is celebrated in Russia as both a theologian and a historian. He is a classical composer who has written multiple grand oratorios, one of which was performed on a tour through the United States. He also had a promising career in the Russian military before leaving to become a monk in 1987.

Prior to his dismissal, Hilarion also maintained an important liminal, if illiberal, space in the ecumenical landscape. On the one hand, he was a staunch advocate of both his church’s membership in the WCC and its robust engagement with the West. He served on the executive and central committees of the WCC and on the presidium of its Faith and Order Commission, which undertakes collective theological studies toward the end of uniting the churches of the world in common life, and he is said to have developed a personal relationship with the last two popes.

On the other hand, Hilarion has also spoken out publicly against both same-sex marriage and the ordination of women as bishops in the Anglican Communion. More damningly, he defended his country’s persecution of Jehovah’s Witnesses, claiming that adherents of that tradition “erode the psyche of the people and the family.”

All this notwithstanding, many were initially surprised and thankful when he spoke out against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. He was subsequently silent about the war for a time, a stance which cost him yet another concurrently held prestigious post, this one in the theology faculty at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland. In an official communication responding to that dismissal Hilarion claimed that, behind the scenes, he was “doing everything possible to help those in need and to end the conflict.” The fact that he has been removed from his position of authority in the ROC adds credibility to his claim, but it paints a grim picture for the future of ecumenical relations with that body.

Hilarion’s replacement is the far less renowned Metropolitan Anthony (Sevryuk), a Kirill loyalist who served as the patriarch’s private secretary before his accelerated ascent through the ranks of church leadership. (He became a bishop at age 31 in 2015.) The young cleric is infamous in ecumenical circles for having discouraged Catholic and Orthodox Christians from attending one another’s masses—or even so much as praying together—which bodes ill for his future working relationship with other churches in the WCC.

It’s not clear how Anthony will use his bully pulpit at the general assembly; after all, he may or may not be poised to withdraw his church from the WCC altogether. Much hangs in the balance—primarily for the Ukrainians whose lives remain threatened by Russia’s criminal war, but also for global ecumenism. There is every reason to expect the worst.

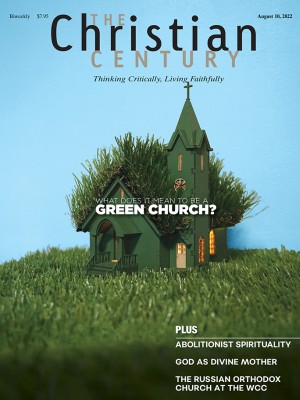

A version of this article appears in the print edition as "Tough choices in Karlsruhe.”