Whose religious freedom is at stake with Texas’s new abortion law?

Some rabbis are claiming that SB 8 violates the obligations of their faith.

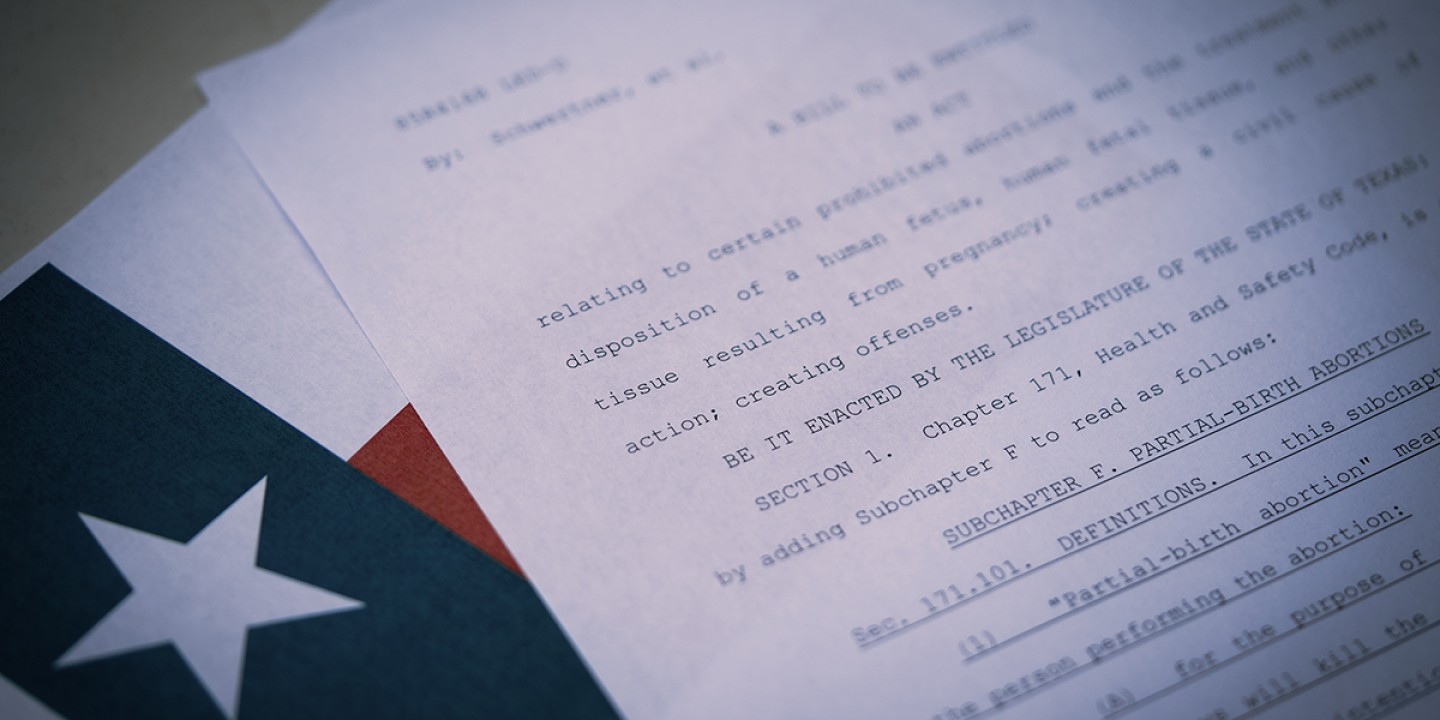

This summer the Texas legislature banned abortions after six weeks of gestation or at the moment when a heartbeat can be detected in a fetus. In order to evade judicial review, this law provides for enforcement not by any government entity but by the public, who have the option to sue any person or organization that they suspect of helping a woman have an abortion after six weeks. The law took effect last month after the Supreme Court declined to block it.

Some of the more surprising objections to SB 8 have come from rabbis who claim that the law violates their freedom of religion. Jewish law, they argue, not only allows for abortion after six weeks but in some cases requires it. Furthermore, Jews are required to offer their neighbors aid—yet the new law prohibits them from offering aid to a woman seeking an abortion.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

These rabbis argue that SB 8 is based on an explicitly and exclusively Christian understanding of personhood. Texas governor Greg Abbott referred to this view in his remarks at the bill’s signing: “Our creator endowed us with the right to life, and yet millions of children lose their right to life every year because of abortion.”

“Judaism teaches that potential life is sacred,” writes rabbi Danny Horwitz in an article for Religion News Service. “Nevertheless . . . that a fetus is not a human being. . . . is directly derived from Scripture.” Horwitz quotes rabbi Byron Sherwin: “Judaism is neither pro-life or pro-choice. It depends on the life and it depends on the choice.”

This is not the kind of pro-abortion rights argument we are most accustomed to. Usually such arguments rely on concepts of individual rights and freedoms, which are then pitted against different assertions of individual rights and freedoms by abortion rights opponents. This rhetorical stalemate has dominated the abortion debate for many years.

These rabbis do not deny individual rights and freedoms, but they situate them inside the context of community, tradition, and scripture. Furthermore, their approach does not require every Jewish person to agree on the exact dynamics of abortion, because disagreement is inherent to the tradition. Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg wrote in Forward in 2018 that Jews “have long been wary of legal maneuvers that appear to be coming from a place of Christian religious conviction” and that the Jewish tradition of machloket, divergent opinions, “makes a Jew who feels personally against abortion more able to see the possibility that someone else might legitimately understand the world in a different way, and to value that perspective.”

Of course, Christian clergy are also among those trying to block the law from taking effect and pursuing legal action going forward. And Christianity has a complicated history on the subject of reproductive rights and personhood. But our Jewish brothers and sisters can show us what it looks like to situate our abortion arguments not in the context of partisan politics but in the context of faith—and what it might mean in this country to truly take religious freedom seriously.