Jesus’ risen, mutilated body

In Luke’s postresurrection appearances, the disciples have to reckon with the traumatic somatic.

Almost 65 years ago, Mamie Till-Mobley decided to have an open casket at the funeral of her murdered son Emmett Till. Weeks before, this young mother from the south side of Chicago had sent her 14-year-old son on a train to Money, Mississippi, to visit relatives. For allegedly whistling at a white woman, Till was abducted, beaten, shot in the head, and dumped in a river. His body was discovered three days later, and although Mississippi officials advocated for a quick burial, his mother demanded that it be sent home to Chicago, where thousands of people attended the funeral on September 3, 1955, at Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ.

By making a public display of her son’s mutilated body, Mobley was insisting that America gaze on the reality of Jim Crow brutality. The body, so disfigured that Till was identifiable only by the initials on a ring on his finger, was viewed by thousands of people and photographed and published in newspapers and magazines. “She saw Emmett as being crucified on the cross of racial injustice,” says Lonnie Bunch, founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, in a comment to Smithsonian. “She felt that in order for his life not to be in vain, she needed to use that moment to illuminate all of the dark corners of America and help push America toward what we now call the Civil Rights Movement.” Indeed, this moment sparked that movement to life months before the Montgomery bus boycott—though historian Elliott Gorn points out that this awakening was only among black folk; most white people didn’t see pictures of Till until decades later.

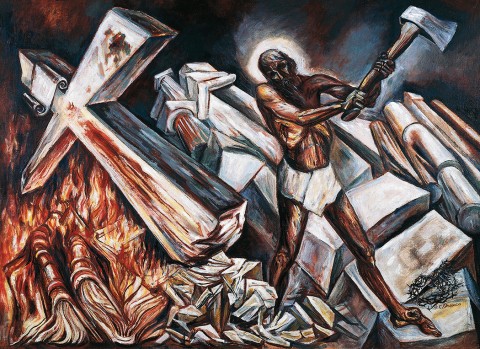

In Luke’s Gospel, the risen Christ offers a similar challenge to the disciples: they have to reckon with his mutilated body, with the traumatic somatic. Yet First World artistic depictions of the risen Christ—both classical and contemporary—are typically glorified, sanitized, and bleached white. These sentimentalized reproductions function to stunt our political imaginations, and they do little to help us face realities such as social and climate crisis. They reflect docetic theologies that reduce resurrection to a triumphant Hollywood happy ending; amid the carbon and capitalist status quo, they animate only otherworldly distraction.