Chaste romance: The lure of Amish fiction

Calling someone nostalgic is an “affectionate insult at best,” Svetlana Boym has written, and few people appreciate the affection. Although the term has shed its medical connotations—it was first used in the late 17th century to describe the physical ailments of Swiss soldiers stationed in France and Italy—nostalgia remains an unwelcome diagnosis. (Nostalgia comes from nostos, meaning “return home,” and algia, meaning “longing.”) Viewed by many as “an ethical and aesthetic failure,” writes Boym, nostalgia usually evokes bathos and schmaltz. If memory is the respectable and even manly recollection of the past, nostalgia is its cloying cousin, the girl with the soppy smile.

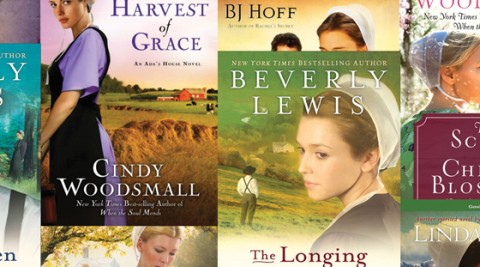

So when an entire genre of fiction coalesces around plots, characters and settings that emerge straight from an imagined past, many have a hard time taking it seriously. Women selling jams and relishes, men with horse-drawn plows turning dark clods of soil, couples stealing chaste kisses behind the barn, families sitting down together for hand-mashed potatoes and three kinds of pie: these are the markers of Amish romance fiction, a subgenre that has astounded observers with its massive success and apparent staying power.

During 2012, a new Amish romance novel appeared on the market about every four days. The top three novelists of Amish fiction have sold a combined total of more than 24 million books, and a quarter of the titles on a recent Christian fiction best-seller list were Amish. Articles about Amish fiction have appeared in Bloomberg Businessweek, the Wall Street Journal, Time, Newsweek, USA Today and Salon, to name a few. And like the Amish, who themselves are spawning new communities at an astounding rate, Amish fiction is calving new genres of Plain romance, including novels about Mennonites, Moravians, Puritans and the Amana colonies.