It looks like a wedding: The new Episcopal same-sex rite

Episcopalians now have an officially approved way to do what some of them have been doing, informally and unofficially, for quite a while. In July the church’s General Convention gave its blessing to blessing. By a surprisingly large majority vote, it authorized for provisional use a liturgy that prescribes what is to be done and said at a service of blessing a same-sex union.

Like every liturgical text, this one is, among other things, an expression of theological convictions. Inasmuch as the Anglican tradition to which the Episcopal Church belongs has typically found its theological identity in appointed forms of common prayer as much as in confessional formulas, it is all the more appropriate to ask what beliefs will be enacted when the new liturgy comes into use in Advent. What does this service say, theologically, about the church that has produced and endorsed it?

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

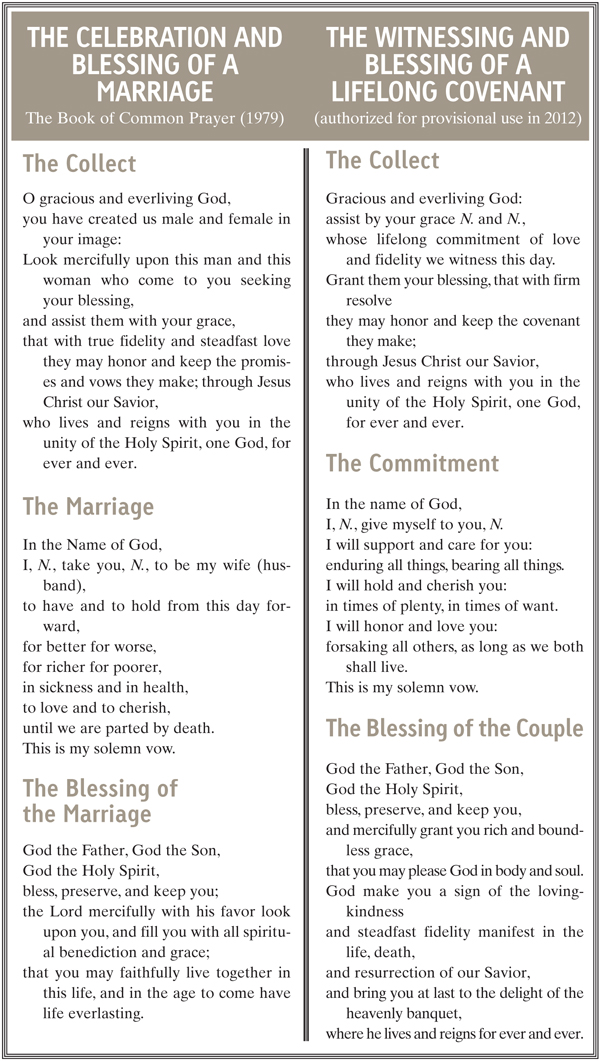

It would be a mistake to suppose that what is most obvious about the rite is what the rite obviously is. What is obvious is how closely the “shape of the liturgy” conforms to what used to be called “The Form of Solemnization of Matrimony” and is now “The Celebration and Blessing of a Marriage.” A congregation gathers; a couple joins them; the presiding cleric explains why they are all there. After readings from scripture and a sermon, the couple is presented and the presider asks each of them whether they truly mean to do what they have come for. Stated prayers are recited. Then each of the two takes the other’s hand, repeats a solemn promise, gives a ring—and finally, on these promises and the couple who have made them, the presider pronounces a formal blessing. Nobody would say, with Shakespeare’s Benedick, “This looks not like a nuptial.” That is just what it does look like.

It would be a mistake to suppose that what is most obvious about the rite is what the rite obviously is. What is obvious is how closely the “shape of the liturgy” conforms to what used to be called “The Form of Solemnization of Matrimony” and is now “The Celebration and Blessing of a Marriage.” A congregation gathers; a couple joins them; the presiding cleric explains why they are all there. After readings from scripture and a sermon, the couple is presented and the presider asks each of them whether they truly mean to do what they have come for. Stated prayers are recited. Then each of the two takes the other’s hand, repeats a solemn promise, gives a ring—and finally, on these promises and the couple who have made them, the presider pronounces a formal blessing. Nobody would say, with Shakespeare’s Benedick, “This looks not like a nuptial.” That is just what it does look like.

Yet a nuptial it is not. The Episcopal Church has not endorsed marriage equality. Neither church law nor the Book of Common Prayer entitles two persons to marry each other, or a member of the clergy to officiate at the marriage, unless one of the two is a woman and the other a man. General Convention did nothing to change that. The rite it did approve studiously avoids the terminology of marriage, let alone matrimony; what the presider pronounces when all is said and done is that the couple are “bound to one another in a holy covenant, as long as they both shall live.” Whether this form of words can be construed as constituting civil marriage in those states that permit two men or two women to marry, the lawyers will have to decide. If it can, the paradoxical consequence would seem to be that a same-sex couple, legally married by an Episcopal cleric acting with episcopal permission as an agent of the state, will not be married according to the church’s own rubrics and canons.

Appearances notwithstanding, then, the new liturgy makes no claim that couples of the same sex can, in the ecclesiastical sense, marry. What it does say is more interesting. It says, explicitly and by implication, that two persons, both men or both women, are capable of making with each other a covenant so sacred, so religiously or spiritually significant, as to invite public recognition, welcome, celebration and benediction on the part of a Christian community in an act of Christian worship. This capability is not, perhaps, self-evident. It needs to be argued for, and the argument needs to refute a well-worn syllogism: “The church can bestow its blessing only on what God already favors. But God does not favor same-sex coupling; far from it. Therefore . . .”

The commission that framed the new rite appears to have taken this reasoning seriously. The long apologia it provided implicitly accepts the major premise: liturgical blessing is not creation ex nihilo; while it indeed makes something new begin to happen, it does so on the basis of something which, by the grace of God, is already happening. A formal blessing on the part of the church is both thanksgiving for what happens and petition for its continuation, enhancement, perfection. It follows that promises, which initiate but do not necessitate some determinate future, are eminently blessable—depending, of course, on what future is being promised.

In the case of the new Episcopal liturgy, the couple promise to support and care, hold and cherish, honor and love, forsaking all others, as long as they both shall live—vows much the same as those made by brides and bridegrooms. The theological question is not whether two women or two men can genuinely utter this kind of performative speech. Of course they can. The question is what they are performing—what their speaking does and whether doing it can be an effective sign, a “sacrament,” of divine grace.

To judge by the rite itself and the apologia that comes with it, promising to live together faithfully and lovingly can be, God willing, cooperation with God in bringing about the eschatological consummation, the new creation, that is God’s own promise. Or, to put it as the commission does, what this liturgy for witnessing and blessing witnesses and blesses is a covenant that embodies the church’s missional character as the people of God in the world. Either way, it is collaborative participation in the divine purpose that makes the lifelong union of two persons not only blessable in itself but also a blessing to others.

By building its argument around the forward-looking biblical notion of covenant, the commission responsible for proposing the new liturgy has taken a theological stand somewhat removed from the traditional Augustinian concern with quarantining sexuality. The vows themselves are traditional enough, but the rationale for blessing them has shifted toward discerning in relations of intimacy anticipations of the life of the world to come. This shift—from Genesis to Revelation, so to say—is evident but not obtrusive throughout the new liturgy: in the opening address to the congregation, in the collects and the petitions of the litany, and (if they are used) in the eucharistic preface and postcommunion prayer.

But never does the wording call attention to the fact that the two principal ministers are both men or both women. Although that fact is the reason for composing a new liturgy in the first place, it is almost incidental to the liturgy as composed. The text could be used, just as it stands, by a man and a woman. They would be inaugurating a covenant with the same content, meaning and purpose as the one same-sex couples will make. Conversely, the theological rationale for blessing a same-sex couple’s union applies equally well to marriage as the Episcopal Church now defines it.

At least one diocese, in a state where same-sex marriage is lawful, has already taken this theological trajectory to its logical conclusion. Diocesan clergy have their bishop’s permission to use a single, multipurpose rite when presiding at a marriage—any marriage—and the rite they are to use is a slightly tweaked version of the one approved at General Convention. Perhaps that is what the commission had in mind all along. For the theology on which its liturgy rests does not attempt to justify same-sex covenants as unique or exceptional; it regards them, as it does marriages in the conventional sense, simply as variations on the same theme.