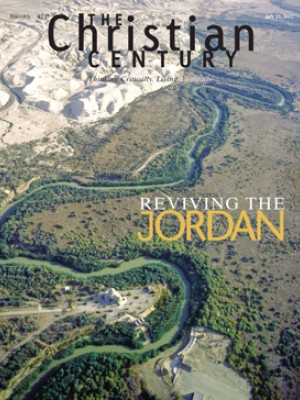

River revival: Can the Jordan roll again?

A stroll along the Alumot Dam on the Jordan River is on no one’s list of holy sites in the Holy Land. Yet the interface between the holy and the profane happens here all day every day. The experience is available for every visitor without ritual and with no need for spiritual discipline beyond the ability to use visual or olfactory perceptions. The Alumot Dam has no entrance fee, but your soul may pay a price for the visit.

The dam is located less than two miles from the southern end of the Sea of Galilee, from where the Jordan River, the world’s lowest river, flows out and heads toward the Dead Sea. Between the Sea of Galilee and the dam, the Jordan can be seen from a heavily trafficked highway bridge as a refreshing wave of blue-green rolling water. On a hot day, which most days are in this region, the view generates a strong compulsion to quench your thirst, both physical and spiritual, with a long, cool drink from the river.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

For many visitors, this view is an inspirational glimpse of the “mighty Jordan,” the river considered holy by Christians, Muslims and Jews—half of all humanity. I am surely not the only one whose heart spontaneously sings a medley of Jordan River songs every time I glimpse the river here: “The Jordan River is deep and wide, hallelujah / Meet my mother on the other side . . . The Jordan River is chilly and cold . . . / Chills the body, but not the soul, hallelujah.” Or maybe: “Roll River Jordan roll / Meet me at the bank of the beautiful river / There will be trial and tribulation along the way / And I’m makin’ way for a better day.”

Just beyond the bridge’s overlook is the Yardenit Visitors Center where each year over 600,000 Christian pilgrims hold prayer services and baptismal ceremonies, plunging into the Jordan from conveniently placed stairs. Activities of a more secular nature happen a few hundred meters further downstream, where kayaks are rented for paddling on the remaining flow of the Jordan, which is dredged and maintained for recreational use until it dead-ends at Alumot Dam.

The dam itself looks unremarkable. It consists of a few meters of dirt road along some still water. A large overflow pipe, emblazoned with a reassuring hiking-trail marker, sticks out over the water and disappears under the dirt berm of the dam. The eye looks across the dam to the shady undergrowth on the other side: the Jordan River must be down there. But when you look down, no water is visible. Yet you hear the sound of rushing water.

The dam itself looks unremarkable. It consists of a few meters of dirt road along some still water. A large overflow pipe, emblazoned with a reassuring hiking-trail marker, sticks out over the water and disappears under the dirt berm of the dam. The eye looks across the dam to the shady undergrowth on the other side: the Jordan River must be down there. But when you look down, no water is visible. Yet you hear the sound of rushing water.

Then you begin to notice a smell drifting up from that side of the dam. There! Partly concealed by rocks and behind a huge eucalyptus tree, water shoots from a pipe and pours over the rocks along the embankment.

A nearby sign and another whiff of the breeze explain what is happening: a mix of raw and partially treated sewage, combined with diverted saline spring water, is being emptied into the Jordan riverbed. Further on, agricultural runoff joins the formula, together with more waste water. This is today’s lower Jordan River.

Because Jordan, Syria and Israel remove nearly all the fresh water from the river and its source streams, the lower Jordan has been reduced to a mere 2 percent of its natural flow—and that trickle is heavily polluted with wastewater from all three countries. The river barely reaches the Dead Sea. Because of this massive environmental ravaging of the river, over 50 percent of the biodiversity of the river valley has already been lost.

Standing on Alumot Dam, one seems frozen in a moment in time, standing between the glorious River Jordan of the past and the sewage canal that the river has become. The history and holiness of this river inspired evolution and revolution in human society over the past 3,000 years. Crossing or immersing in the Jordan, whether literally or figuratively, is heavily symbolic. That the river marks the divide between exile and home is as relevant for both Israelis and Palestinians today as it was in biblical times. For a contemporary American example, it is difficult to imagine the American civil rights movement without the vision, hope and courage evoked by the songs about the Jordan River sung by activists in marches and church gatherings. The Jordan River’s symbolic legacy provided inspiration that helped catalyze a societal revolution, correcting grave injustices and changing the understanding of what America is.

But the Jordan today is too shallow and narrow for Michael to row a boat across, and the shore is a stinking pile of organic sludge. The water may or may not chill the body, but it will certainly give you a skin rash, if not full-blown dysentery. You can’t cross to the other side because stray land mines swept up by the river from old minefields make it too dangerous. And mother isn’t waiting on the other side—army patrols have declared it a closed military area and block access. In contrast to its glorious past, the sight and smell of the sewage downstream appears as a prophecy of where contemporary society is headed.

What possibly redemptive message is there to discover in today’s Jordan River from which future generations might gain inspiration? While there is always an expectation that heaven and earth meet in the Holy Land, when you look at today’s Jordan River, you mainly see a reflection of human greed and shortsightedness.

Nevertheless, something redemptive is happening in the lower Jordan River. Though significant “trial and tribulation along the way” remains, community activists and environmental professionals are showing that citizens of the region can still “make way for a better day” on the Jordan.

The movement is being led by Friends of the Earth Middle East, for which I work. It is the only joint Palestinian-Israeli-Jordanian nongovernmental organization in existence. The work of this NGO shows that in the Middle East—where the problems are big but the land is small, where “my pollution” is “your pollution” and vice versa, and where water is scarce and flows under and over and along the borders—progress requires cooperation. It also shows that cooperation can happen.

FoEME’s approach is both sensible and obvious. Its experience has been that when it comes to the environment, local self-interest can overcome national antagonisms. As a result, work on environmental issues can be a fulcrum for peacemaking.

Ten years ago, FoEME launched the Good Water Neighbors program, which identified pairs of Israeli, Jordanian and Palestinian cross-border communities that shared water resources. FoEME encouraged local residents to set up shared water awareness and conservation projects. Most notably, youth “water trustees” in each community were trained to take responsibility for their local water resources and later were introduced to their peers across the border. By comparing maps of local environmental hazards that the youths themselves created through months of work, they quickly realized the impact they had on each other’s lives and their shared dependency on adequate and clean water resources.

In their home communities, the youths and others appealed to local government leaders to work for water improvements. Over the years, five pairs of mayors signed Memoranda of Understanding in which they pledged to work across the borders to resolve shared environmental problems. Over the past three years, FoEME has helped leverage over $200 million of investment from international agencies for the now 28 GWN communities, helping them implement the memoranda agreements and improve the water resource infrastructure.

Which brings us back to the Jordan River. Standing on the Alumot Dam’s dirt road, one can see something besides pollution. Less than a minute’s walk from where the sewage pipe spills out into the riverbed, heavy machinery is building a wastewater treatment plant for Israel’s Jordan River Regional Council, one of FoEME’s strongest GWN communities. Further downstream, in the city of Beit She’an, another GWN community, a new waste treatment plant is already operating. Across the border in Jordan, the GWN community North Shuna has a similar plant under construction. Further south, in GWN Jericho, plans and funding are in place for another treatment facility. When all these plants are online in a few years, almost no municipal sewage will enter the Jordan.

Like an apothecary treating a seriously ill patient, environmental activists in the region need a wide array of formulas and medicines. Besides encouraging bottom-up community organizing and connecting community projects with foreign development agencies, they’ve had to address national authorities as well. After FoEME’s persistent urging, the Israeli environment minister pledged to return fresh water to the Jordan for the first time in over 60 years. Although only 30 million cubic meters of water per year has been pledged—less than 10 percent of what is needed to make the Jordan’s rehabilitation viable—it will be enough to ensure that the Jordan doesn’t run dry in hot months.

Which raises the stickiest set of problems: What happens to the water downstream? A few miles south of the Sea of Galilee, the Jordan becomes the international border between Israel and Jordan, and then it flows past the 1967 Green Line into the Palestinian West Bank. Water is the thirsty Middle East’s most valuable resource, and climate change and population growth are already making water demand even greater and thus potentially more contentious. Will continued inequality, mutual suspicion and competition over water ensure resource sustainability and mitigate tensions, or would cooperation and striving toward water justice make the more effective program?

Again, FoEME’s appeal to collective self-interest models a way to manage the water more efficiently and share it more equitably. Contested water causes costly conflict, while shared water creates a disincentive for all sides to tolerate pollution or waste from anyone. Water justice for all of the region’s residents is more than an ideal—it outlines the long-term strategy for providing sufficient water for anyone: by providing it to everyone.

Thus, FoEME is working to create a first ever regional master plan for the lower Jordan River. FoEME’s master plan will bring together a master plan already being developed by the Israeli government for the Israeli portion together with new master plans to be developed for the Jordanian and Palestinian sections. To gain grassroots support, FoEME is organizing stakeholders to voice their interests and needs through a Jordan River Council, which includes local business and community leaders from each country alongside religious leaders who consider the Jordan River holy and want to see it healthy again. Local and national water officials and leading experts participate in discussions, commenting on FoEME’s studies as they progress, despite their concerns that they will have to give up some fresh water to rehabilitate the river. FoEME’s regional meetings provide a rare opportunity for Jordanians, Palestinians and Israelis to sit around the table together to discuss rehabilitation efforts.

Other pieces of the puzzle are also being put into place. As the Dead Sea continues to shrink, largely due to lack of water from the emaciated Jordan River, FoEME and other groups are organizing supporters of the Dead Sea to help the Jordan River as well. FoEME operates the Sherhabil Bin Hassneh EcoPark in Jordan and the Palestinian Auja Village EcoPark, which, with their guesthouse facilities and community tourism focus, help promote ecotourism as a viable economic alternative to water-intensive farming practices in the Jordan Valley. Ecotourism income gives partners an economic interest in making the Jordan an inviting—and profitable—piece of the natural world once again.

FoEME has plans under way to create the transboundary Jordan River Peace Park at the confluence of the Jordan and Yarmouk rivers. The aim is for this to be a shared space, bridging the border and modeling the benefits of river cooperation on the Island of Peace which lies between Israel and Jordan. With the force of the mighty old Jordan in mind, hope is renewed and vision sparks. The river of justice, the river of peace, may flow yet again.