Criminal negligence: The scourge of world hunger

I should have seen my road to Damascus moment approaching. I’d been warned.

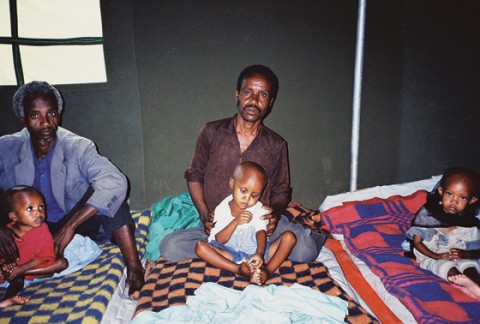

“Looking into the eyes of someone dying of hunger becomes a disease of the soul,” Volli Carucci of the United Nations World Food Program told me on my first day in Ethiopia.

A disease of the soul? I had received an overdose of medical admonishments during my many years of covering Africa for the Wall Street Journal: Get your yellow fever shot. Don’t forget the malaria pills. Beware bilharzia in standing water. Avoid the meningitis season. Be cautious in the cholera zones. But never before had I been warned about my soul. Now where, I wondered dubiously, could I get a shot or pill for that?