Bearing the scars

Years ago, at a barbecue in Argentina, I realized I was the only person present who wasn’t a survivor of torture.

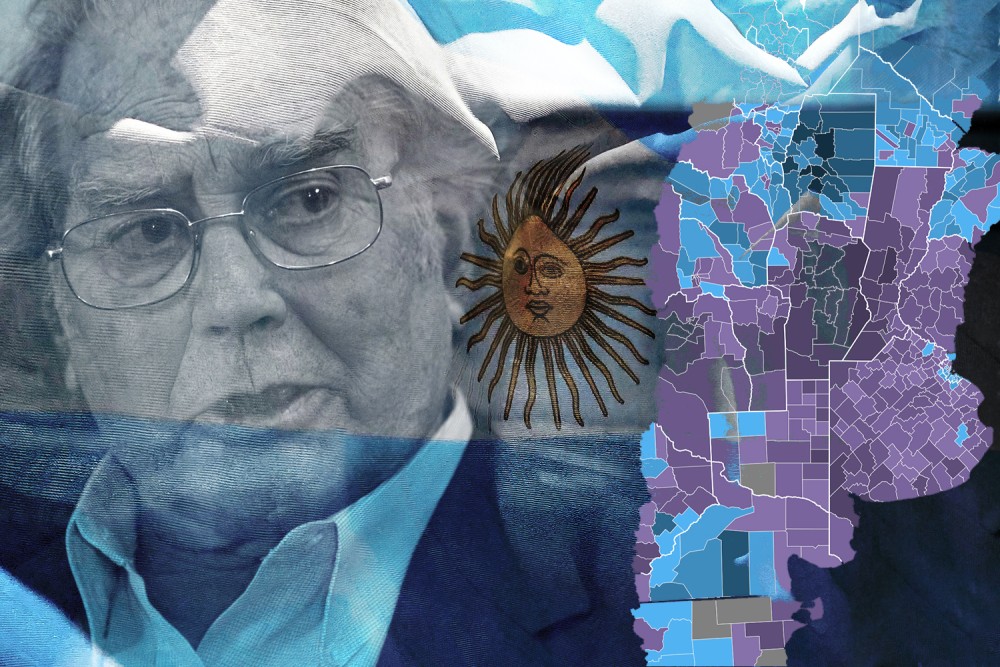

Adolfo Pérez Esquivel of Servicio Paz y Justicia in Argentina (Source photo: Romina Icaza / Asamblea Nacional)

The recent election of Javier Milei as president of Argentina—with his telling slogan “Make Argentina Great Again!”—brought back memories of studying and living there. I was there during the Dirty War in the 1970s and early ’80s, which pitted a military dictatorship against the Argentinian people, leading to the kidnapping and death of some 30,000 people, many of whom were tortured before being dropped from planes into the ocean. Milei has his own version of events favorable to the dictatorship.

In addition to attending seminary, I volunteered with a human rights group, Servicio Paz y Justicia. The leader of the organization, Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, invited me to a small gathering at his home. When I arrived, it seemed like a typical Argentinian barbecue. The air was filled with the rich smoky scent of chorizo, beef, and chicken on the grill. A makeshift table had been set up in the garden under orange and lemon trees. A few people were strumming guitars, and there was singing, laughter, and hugs as others arrived.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

As the afternoon wore on, I became aware that I was the only person at the party who was not a survivor of torture. Adolfo himself had been tortured and held without trial for over a year before his release. It was a warm day, and while I tried not to stare at bared arms and legs, some torture scars were visible, ugly signs of the worst that humans do to each other. The scars held a strange beauty as well, emblems of commitment to the struggle for human rights regardless of the consequences.

I was welcomed, but I could not know what it was like to be subjected to torture. The others had the same kinds of scars, a sign of solidarity that said, “You are one of us. You know.” And while no one would wish that terrible knowing on anyone, it had become a source of strength, and even comfort, which allowed them to sing, embrace, and feed their wounded bodies, finding joy under the citrus trees.

On Easter evening, Jesus appears among his followers and shows them the scars of crucifixion torture that he still bears (John 20:19–20). This is how they are able to know him and trust him as one with authority to lead them from despair to hope and from death to resurrection life.

When I served a church in the Bronx, I learned to love singing the African American spiritual “I Want Jesus to Walk with Me.” I do want that. When I suffer, when I hurt, when my heart is broken, I want Jesus to walk with me. But do I want to walk with Jesus? Jesus’ solidarity with my personal suffering is one thing. The present-day ramifications of his solidarity with collective, systemic suffering under the Roman Empire is something else. For a person of privilege, it leads to some very uncomfortable places. Yet systemic oppression is the context that produced the spiritual and that found the disciples hiding out in the Upper Room.

I had a coffee-hour conversation back in Advent with a highly committed church member. A conversational study on racism had been announced, but the topic was later changed to the Advent and Christmas stories in Luke. She told me that if the original topic had remained, she would not have attended. During Advent, she wanted something more spiritual. She is hardly alone. Facing systemic racism and White supremacy is not part of what most predominantly White churches consider under the category of spirituality. During Advent, we have even become accustomed to singing the Magnificat without being unsettled by its revolutionary content.

Time for communal worship, regular prayer, retreat, reflective reading, and various artistic endeavors are all activities we tend to associate with spirituality. Yet anti-racism work, community organizing for fair wages, human rights, and other work assigned to the social justice category are also practices that nurture the Spirit. Jesus did not put the Spirit into one box and such Spirit work in another. This seems clear when he begins his ministry proclaiming that the Spirit anointed him to bring good news to the poor, release to captives, and freedom for the oppressed.

I do not blame the church member who sought spirituality without discussing difficult subjects. For centuries, most majority-White churches have taught the separation of spirituality and social justice. It’s also true that our lives are bombarded by divisive, exhausting, and stressful rhetoric and realities. Who wants more of that in church? Perhaps an Advent study is better suited toward the more typically spiritual side of faith. But in what season do we prefer to face unsettling truths?

My friend Francisco Herrera recently wrote on Facebook,

When I cry “decolonize” what I’m really saying is “Remember!” When you break from the old to embrace the new, wounded memory causes us to either create a glorified past that is free of our tormentor’s influence, a past that likely never existed, or a future that somehow is magically free of their violent influence. But both of these are self-serving illusions. Instead we have to be honest about what the church has done and continues to do, and use this dark history to help shape how we see who we are and where we are, where God is calling us, and how to get there.

Yes, even when it means anti-racism in season and out of season.

I’m moved by the example of German bishop Bärbel Wartenberg-Potter, who retired and visited New York City, where I met her for lunch. She was bishop over the same area where the Nazi bishop Erwin Balzer once served. Balzer draped the church in red and black Nazi flags and preached murderous sermons from the pulpit. Wartenberg-Potter told me that when she and others went into the church treasury to find a pectoral cross for her to use, they discovered Balzer’s. The golden cross had gold medallions along a chain, each engraved with the image of one of the churches under his care, a beautiful symbol of connection—but on the opposite side, each of the church medallions was engraved with a swastika. When that cross was lifted out of the treasury, the group recoiled—but Potter said, “I want that one.” She had the swastikas removed and told me that she wore it from then on as a reminder of the grim history she carried with her, so that it might inform her mission and ministry going forward.

We all bear the scars of the injustices that mar the skin of our shared humanity. We are all called into the terrible knowing—and difficult work—that will ultimately become a source of strength, allowing us all to sing, embrace, and feed our wounded bodies, finding joy together under the tree of life.