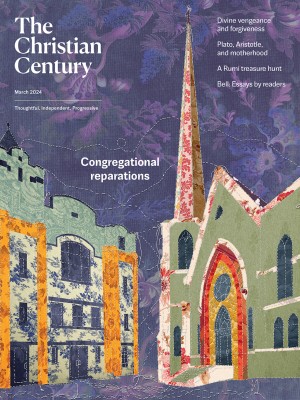

(Illustration by Xia Gordon)

This is the time of year when my thoughts always turn to Annie Dillard—the kind of bog-wet March days in the Midwest when you sense that turn in the air, a greenness coming up. I read Pilgrim at Tinker Creek every few years and dip back in and out of it often. I’ve translated passages from it into Latin as a class exercise (Campanam fueram per vitam meam totam), and among my prized possessions is a first edition, signed by the author. It’s not necessarily a springtime book—it encompasses the wheel of the year or something like it—but spring is when I really feel it, mud on my boots, the desire for a wind-chapped face and the kind of walk you might want to call a tramp through some trees.

Winter is hard on me, for the same reasons it’s hard on a lot of people. I live in Chicago, famously a cold place with a long winter. I’m naturally kind of an indoor person, and initially there’s nothing wrong with spending all my days within the confines of my house, or running from one appointment to another as fast as I can with only my eyebrows exposed to the wind, but eventually the seasonal depression, the cabin fever, the lack of vitamin D all creep in. It isn’t really that I personally miss aimless walks outdoors, or dawdling, or feeling actually warmed by the sun; it’s more that I forget those are even options available to anyone.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

March here is just as likely to dump six inches of snow as it is to be mysteriously, worryingly 80 degrees, but even in the lion portion of the month, you sense it more than you see it, a kind of tennis ball–green halo around the ends of branches, a suggestion of a world that looks different from the slush gray of February. Suddenly, I become aware of new possibilities—this is the month in which, inevitably, I freeze half to death because I’ve optimistically set out for the day in a light sweater and flimsy footwear. My notebooks fill up with diagrams of garden beds and observations from the window. Life returns.

Dillard considered Pilgrim at Tinker Creek a work not of nature writing but of theology, so it’s time, then, to zoom in a little closer, past the newly unfurled leaves and the flowing sap, past plant cells and chlorophyll, to questions of God. On its surface, Pilgrim might seem like a cataphatic text—one that sets out to describe God through enumeration of God’s many wonders: the tree with the lights in it, birds and puppy bellies and salamanders sunbathing in extravagant crescents. But the book is just as concerned with the indifferent, unfeeling death and decay involved in the natural world, a giant water bug emptying out the liquefied insides of a frog, the teeming horrors of insect life on planet Earth.

I’m no stranger to these horrors. I spent an entire winter of daily shifts at the divinity school library watching the squirrels in a tree outside slowly eat one of their fallen squirrel comrades, unsheathing his little arm like they were taking off a fur jacket, stashing his frozen body in a hollow in direct view of the window by the circulation desk so only a tuft of his tail fluttered in the wind, right up until the day the tree was taken down to make way for new construction. There was a smug kind of irony I felt in watching that, day after day, right alongside the queasy horror that was related a little to the ways I was feeling about God, reading mystics and monks and people who praised the mystery and the goodness of God down the ages. Well, yes, I would think, but squirrels—adorable, acorn-stashing, quad-scampering squirrels—will eat each other in the dead of winter!

But here too, Dillard argues, is God. Dillard’s approach to the natural world is a hermeneutic one, reading the characteristics of God from the landscape around her suburban Virginia home: even the hunger of water bugs and squirrels has something to illuminate about the Divine. While Pilgrim at Tinker Creek does its best, like Thoreau, to obscure the suburban nature of the landscape she inhabited, you get the sense that even here, in the creeks running out back behind the subdivisions, in the little wildernesses allowed to spring up behind houses, life, and God, are present if you choose to look for them.

In a scene at the very end of the book, Dillard is testing out an ancient Roman theory, that bees can be killed by echoes. When English doesn’t work, she tries Latin. And so she stands in a quarry and watches a bee as she yells out: “Habeas corpus! Deus absconditus! Veni!” If your Latin is rusty, let me translate: “You have the body! Hidden God!” Veni is a little more interesting. It can either be a first-person indicative—Caesar’s “I came”—or a second-person imperative—“Come.” One of my favorite things about Dillard is that she is sly in this way. A jangling together of legal and theological and historical phrases becomes a plea to a God: we have the proof of you, but we cannot see you, come find us.

The bee does not die, God does not come in any way that is observable, and yet, all around her, there God is, there the world is, and what can we do but delve into it? What is for us but to search it down, to keep an eye on the minute and the majestic, the beauties and the horrors, and read God in every line?