Faith, family, and politics in Nigeria

Two debut novels portray everyday life in Nigerian cities. They also teach Americans about our own culture.

Nigeria is by far the largest of Africa’s 54 nations, and its $1 billion economy is fifth largest on the continent. With 51 percent adult literacy, it lags far behind other former British colonies such as Ghana and Kenya, yet it has contributed much—possibly more than any other African nation—to the growing list of novels written in Africa that are read around the world.

Two debut novels by Nigerians, richly textured narratives of family life in both city and village, are attracting critical attention and deserve a wide readership. In each of them, a young narrator observes his elders negotiating the economic and cultural challenges of daily life in postcolonial Africa. Each is set in the 1990s, when Nigeria made halting steps forward in its quest for effective and accountable government and then slipped catastrophically backward. Each illuminates the tensions between African traditions and Western ambitions, between the old ways that have sustained families and communities for many generations and the new ideas that promise but do not always deliver an escape from poverty and isolation.

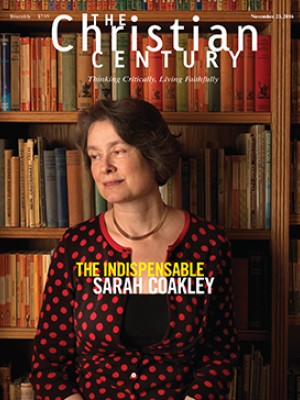

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

When Jowhor Ile’s narrative begins in 1995, the Uku family of Port Harcourt (once a verdant garden city on the Niger delta and now a chaotic megalopolis) is comfortably established in the Nigerian middle class. General Sani Abacha has thrown out Nigeria’s elected government in favor of a military dictatorship, one of several that mar Nigeria’s postindependence history.

Like millions of others across Africa, the Uku family left the village for the city to make a better life. Now the family owns a television, a radio, a freezer, and a telephone—though subject to the whim of the electricity company, the Nigeria Electric Power Authority. “NEPA had a change of mind and restored power,” Ile writes. “A new energy was injected into their evening. They caught the tail end of the news, which was followed by a government-sponsored program about skills acquisition projects for rural women.”

Ile tellingly conveys the optimism and skepticism of the Ukus’ life. The government provides services for the poor, but electricity lasts only a few hours a day. The Uku children are in school, and the oldest has just been accepted to university. They remember to greet elders in the proper way, earning their parents the respect of those who have stayed in the village.

From the voice of a nine-year-old boy, Ajie, we learn of the family’s history—and, at the very outset, of the unexplained disappearance of his eldest brother, Paul. Ajie is a close observer of family dynamics, adults jockeying for influence, and the gradual but dramatic disruption of ordinary life by protests against government repression and the brutal military reprisals they elicit.

Familiar routines of school and work are complicated by strikes and roadside checkpoints as Paul prepares to depart for university. Ajie’s return to boarding school—organizing “the things he needed back in school, legal and contraband”—may be delayed by protesters blocking main roads. But Ajie’s father maintains his faith in the advance of liberal values, and his mother, who brings the children to church several times each week, trusts God for guidance and healing. Through Ajie’s eyes, Ile conveys the resilience of family life in the face of cataclysmic political changes.

Eventually, as the time frame alternates between Ajie’s early childhood and 1995, readers glimpse the darkness that lies beneath the surface. Respected figures in the village flee to the Uku home for refuge after learning that criticizing government policies has put their lives in danger. Important events from Nigerian history are recounted, including the conviction and summary execution of nine critics of the Abacha government. (The most renowned among them—Ile does not mention him by name—was the internationally recognized writer Ken Saro-Wiwa.)

The nine-year-old narrator never solves the mystery of his brother’s disappearance, but Ajie reappears as a young man of 19 in the novel’s brief closing section when the facts at last come to light. Ile’s description of the family’s response, quietly eloquent, underscores the ordinariness of tragic events. “The dead will not be consoled,” Ajie reflects, and “neither will those who live in the skin of the dead.” Ajie will return to his studies in London; his sister will complete her medical training in the United States; and their mother, now a widow, will keep working on her compendium of native herbs.

Chigozie Obioma’s novel is also the story of a family that has moved from village to city and embraced modern ideas, living with the tensions between traditional and modern ways, between Christianity and African traditions. The father and breadwinner of the Agwu family has been sent off to manage a bank branch in the far north, while his wife and six children remain in a more developed city in the south. For nine-year-old Benjamin, the fourth child, life revolves around his three older brothers. Benjamin’s voice from boyhood alternates in the novel with his perspective at the age of 19, looking back and taking stock.

Like Ile, Obioma conveys the political dislocations of the period indirectly through the fortunes of the Agwu family. The narrative begins in the early 1990s when a respected traditional figure, Chief M. K. O. Abiola, is seeking the presidency and the Agwu boys meet him at a campaign stop at their school. In the novel, as in reality, Abiola won the election but the results were annulled, and he spent the next several years in a military prison. The Agwu family follows politics more closely than the Uku family of Ile’s novel, but political events unfold with a sense of fatal inevitability. Ordinary citizens carry on as best they can.

Whereas Ile’s novel is told in simple and direct language, Obioma’s narrative is rich in imagery and metaphor. Chapters open with arresting analogies: “Father was an eagle,” “Ikenna was a python,” “Mother was a falconer.” Sometimes illuminating, sometimes only enigmatic, these images invite us to look beyond surface realities to deeper dimensions.

With their father away, the boys set out secretly to fish in a local river that is both heavily polluted and ritually off-limits. There they meet a madman named Abulu who embodies everything their family rejects: foul-mouthed, ill-behaved, smelling of “rotten food, and unhealed wounds and pus, and of bodily fluids and wastes.” Abulu pronounces prophecies, which may be only the rantings of a disconnected mind or may be messages from a spiritual realm to which he is privy. And these prophecies include a dreadful prediction for the Agwu family.

Mr. Agwu—in the narrative he is always “Father”—returns home and learns of his sons’ illicit expeditions. After administering a reprimand and a beating, Father counsels, “You could be a different kind of fisherman. Not the kind that fish at a filthy swamp like the Omi-Ala, but fishermen of the mind. Go-getters. Children who will dip their hands into rivers, seas, oceans of this life and will become successful: doctors, pilots, professors, lawyers.”

Eventually the madman’s prophecy is fulfilled in a maelstrom of fratricidal conflict. In the aftermath, two of the four brothers are dead. With the third brother, Benjamin plots revenge against the madman. When this brother flees and goes into hiding, Benjamin remains behind to face criminal charges.

By filling in events of the narrative through flashbacks to earlier times of childhood, Obioma constructs characters of depth and complexity. Their spiritual lives are as fragmented and disordered as their actions. They attend church with Mother while fearing the spirits of the river. Never becoming the “fishers of good dreams” their father envisioned, they discover that hope itself is like “a tadpole: the thing you caught and brought home with you in a can, but which, despite being kept in the right water, soon died.”

The Fishermen has gained a remarkable list of awards—short-listed for the Man Booker Prize, winner of the NAACP Image Award, included in countless best-of-2015 lists. Inevitably, it has been compared to Chinua Achebe’s classic novel, and several reviewers have asked whether it is today’s Things Fall Apart. That book makes an unannounced appearance in Obioma’s novel when Benjamin’s brother recounts the story of “the strong man, Okonkwo, who was reduced to committing suicide by the wiles of the white man,” from “a book whose title he could not recall.” Achebe also appears obliquely in Ile’s narrative when the Uku family watches “the mini-series Things Fall Apart” on the national television network.

If Obioma’s book is to be compared with a work by Achebe, a better candidate would be the sequel, No Longer at Ease, Achebe’s tale of a Nigerian who returns from abroad as a hero and reformer but is brought down by economic and spiritual forces he cannot fully understand or control. But there is no need to praise contemporary Nigerian fiction by setting it alongside the work of a half century ago. These works by Ile and Obioma join a crowded shelf of exceptionally engaging fiction by Nigerian writers, many of them effectively living and writing in two worlds at once. Both publishers are North American; Ile resides in Nigeria; Obioma studied creative writing in Michigan and now resides in Nebraska.

Through the gift of fiction, these Nigerian writers offer North American readers an opportunity to see their own culture in a clearer light. Neither of the novels is primarily a narrative of colonial or postcolonial struggle, yet both contribute to what Kenyan writer and theorist Ngugi wa Thiong’o has called “decolonizing the mind.” Two boys of just nine years, Ajie and Benjamin, can be our guides.

Read the interview with Chigozie Obioma.

A version of this article appears in the November 23 print edition under the title “Faith and family in Nigeria.”