A teenage killer’s brain

Tragedies of immense scale seem to mess with our ability to distinguish space from time. “After Hiroshima,” we say, as though the city no longer exists. Place becomes past tense. Spaces where trauma occurred are erased by the trauma itself.

Before April 20, 1999, Columbine was an unincorporated area west of Littleton, Colorado. After Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold walked into their high school and murdered 13 people, wounded 24 others, and killed themselves, the word slipped from location to event. Grieve for the place—Newtown, Charleston, San Bernadino, Orlando—that makes sense to our ears when paired with before and after.

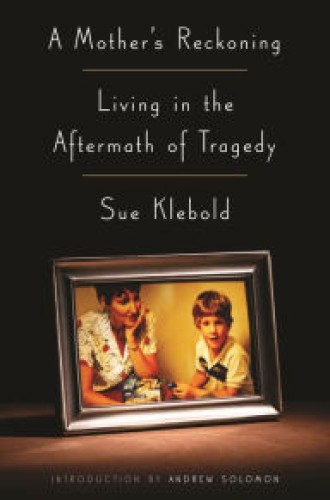

Columbine does not appear in the title of Sue Klebold’s memoir; her publisher knew that her last name would suffice. There were school shootings before Columbine and deadlier ones after, but Columbine remains a reference point. “I will spend the rest of my life reconciling the reality of the child I knew with what he did,” Klebold writes, and her book discloses both the son she knew and the son she didn’t.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

An agonizing requiem for Dylan and his victims, Klebold’s story travels octaves of torment whose singularity could easily isolate her from readers. But it is also a eulogy for the illusions she and all parents share: that our love for our children can protect them from harming themselves and others. You can never fully know your child’s interior life, she tells us. You cannot know the measure of sadness or rage that may be unfolding within that child.

The Klebolds had no idea that Dylan was considering killing himself, let alone anyone else. It is this parental sense of immunity, and the desire to overturn it, upon which her memoir turns. “There were hints that Dylan was troubled, and I take responsibility for missing them,” she writes. “But . . . you wouldn’t nervously herd your child away from Dylan if you saw him sitting on a park bench. In fact, after a few minutes of chatting with him, you’d be more likely to invite him home for Sunday dinner. As far as I’m concerned, it is precisely this truth that makes us so vulnerable.”

The book opens with the unparalleled voice of Andrew Solomon. “I didn’t want to like the Klebolds,” writes Solomon, who interviewed the Klebolds for his book Far from the Tree. “The cost of liking them would be an acknowledgment that what happened wasn’t their fault, and if it wasn’t their fault, none of us is safe.” But Solomon found Sue Klebold to be a person of moral authority and a clarity of vision borne of extreme pain, and his introduction vouches for that. Solomon also confirms her claim that Dylan’s motivations for the attack grew out of suicidal fantasies, while Eric Harris’s motives were homicidal. “Eric was a failed Hitler,” he writes; “Dylan was a failed Holden Caulfield.”

Klebold narrates the surreal first days after the massacre in agonizing detail. From the panicked phone call from her husband that there had been a shooting at the high school, to the slow leak of the truth that their son was not only killed but killer, Klebold describes the stubborn loop of her brain’s denial. Eventually, after she and her husband visited the library in which the shootings occurred and viewed the so-called “basement tapes” that Dylan and Eric had made, any lingering defense mechanisms fell away. The aftermath of which she writes included sifting through journals and photo albums, looking for clues to Dylan’s troubles that she and her husband had missed. It involved her own psychological deterioration, as well as her eventual climb toward activism on mental health issues.

The way one answers the question “Why did Columbine happen?” becomes a Rorschach test for political, ideological, and religious worldviews. “People blamed video games, movies, music, bullying, access to guns, unarmed teachers, the absence of prayer in schools, secular humanism, psychiatric medication,” Klebold writes. One by one, she subverts the authority of any single “why” narrative. The shooters must have been bullied outcasts (Eric was only one of Dylan’s many friends). They must have grown up in gun-loving homes (she and her husband hated guns). They must have played violent video games (they did, but it’s a rare adolescent boy who hasn’t played Call of Duty).

The closest she comes to answering the why of Dylan’s actions is brain illness, a term Klebold chooses intentionally in order to root mental illness in biology. “Major depression with transient psychotic episodes” was the diagnosis of one researcher who analyzed Dylan’s journals. Klebold, who is donating her royalties to charitable causes, wants parents and teacher to learn to recognize the indicators of brain health of young people so that they can identify its decline. Take warning signs of brain illness seriously, she pleads. Probe and probe and probe some more. Get help.

That Klebold’s activism would center on this particular dimension of Columbine makes sense. Yet many will find her treatment of the role of guns in the massacre to be quite thin. Sixty-four school shootings occurred in the United States during 2015, and the number of gun murders per capita in the United States is nearly 30 times higher than that in Great Britain. Laser-focused on psychological distress, Klebold gives scant attention to the wider context of the gun culture. Dylan and Eric bought an assault pistol from a pizza shop employee, and a friend bought rifles for them at a gun show. Yes, we are vulnerable because we might not recognize a troubled Dylan Klebold on a park bench. But just as worrisome is the fact that he might have just bought a handgun off the pizza guy.

Reading Klebold’s memoir is harrowing. I have three adolescent sons whose lives and affections resemble Dylan Klebold’s—white, suburban, middle-class, with an intact family and a love for baseball and the outdoors. Frankly, I find parenting overwhelming enough without fearing that the boys down the hall are ticking time bombs of suicidal or homicidal desire. Everyday teenage gestures—this shoulder shrug, that scorn-tinged retort—can be indications of deep-seated depression, and it is these gestures that Klebold wants me and other parents to learn to read carefully. I do not disagree.

Yet does the anxiety that Klebold’s story provokes help me become a better parent or merely a more neurotic one? Since reading Klebold’s book, I have indeed checked my sons’ texts more frequently and probed a bit more into their sullen moods. I hope to be an adult who recognizes when the adolescents in my life are in distress. But will anxious hypervigilance produce an intimacy that staves off trauma? Can we ever fully know our children’s private lives? Should we? If not, is our only recourse to live in apprehension that they are on the verge of killing themselves or others?

Parenting teens is rife with such vexing questions. As a parent, I need other caring adults to know my children and to be attentive to warning signs that I might miss. In that sense, Klebold’s book underscores the value of intergenerational relationships and mentoring programs. That’s not to suggest that Dylan wouldn’t have become a killer had his family gone to church. It’s merely to say that belonging to an authentic, committed community of faith can make an adolescent’s journey a bit less alienated—and a parent’s task a bit less fraught with fear.

Klebold didn’t have to tell her story, but she tells it now with courage and candor. “All I wanted to do was to hold my son,” she writes, “and then to have one more chance to stop him before he committed his final, terrible act.”