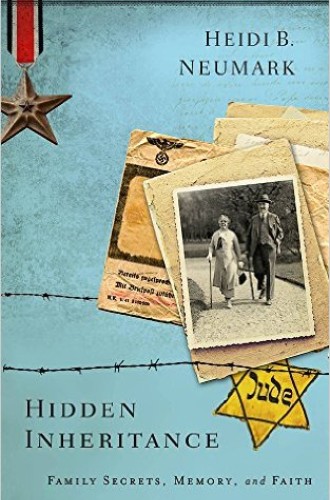

Unexpected ancestors

Few secrets are as devastating as those that make us rethink our entire identity. Lutheran pastor and author Heidi Neumark learned that her family harbored such a secret when her 22-year-old daughter Googled the name “Neumark” one evening and discovered a great-grandfather very different from the one she had been told about, and a family history of which her mother knew nothing.

Neumark knew only that her father had immigrated to the United States in 1938, when he was 35 years old; that he was a devout Lutheran who kept his framed confirmation certificate (in German) on his bedroom wall; and that he came from a prosperous family in Lübeck, Germany. As a child she frequently visited her grandmother, who lived in Switzerland, and she knew her father’s sisters. The aunt who lived near them was also Lutheran.

Her father was proud of his German heritage, and the family cooked German food and celebrated Christmas the way her father had celebrated it as a child in Germany. Nothing prepared her for the discovery that her father was Jewish and that her grandfather, Moritz Neumark, had died at Theresienstadt (Terezín), a concentration camp in what is now the Czech Republic.