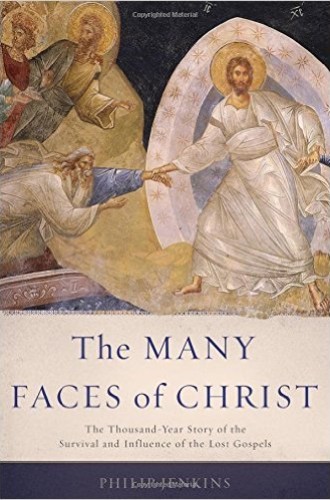

The Many Faces of Christ, by Philip Jenkins

Jenkins contends that the so-called lost gospels were in use continuously in late antiquity and the Middle Ages, despite church authorities’ efforts to exclude extracanonical treatises. His abundant proofs of continuity give lie to the traditional assumption that all but the four canonical Gospels were effectively squelched in the fourth century. According to Jenkins, a professor of history at Baylor University, it was not until the Lutheran Reformation of the 16th century that their use dramatically declined.

Many factors must have contributed to the attraction of the extracanonical gospels—and “must have” is a favorite phrase of historians who have plenty of evidence but little explanation. The long endurance of the lost gospels was apparently due to a desire for a fuller picture of figures and events reported by the canonical gospels, such as the childhood of Jesus; the conception, childhood, and death or assumption of the Virgin Mary; and the harrowing of hell.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Jenkins argues that a dualism of matter and spirit informs extracanonical literature from antiquity through the medieval centuries. But dualistic ideas may also have been supported by an experiential intuition that matter and spirit, light and darkness, body and mind are not only separate, the result of different creations, but engaged in ongoing conflict. It is perennially impossible to ascertain whether experience tends to reflect the ideas to which one is committed or whether experience precedes and forms the ideas. Deeply antagonistic to the doctrines of creation, the incarnation, and the resurrection of the flesh, the lost gospels reveal the huge diversity of the Christian world.

Although church leaders through the medieval centuries excluded readings from the lost gospels from the liturgy, stories from those gospels played a quasi-liturgical role. Worshipers were surrounded by images that told many of the stories from the extracanonical gospels in vivid visual—rather than verbal—language. The Many Faces of Christ demonstrates that an accurate impression of the diversity of Christianity cannot be formed from prose texts alone. The lost gospels appeared throughout medieval Christian history in images and poetry as well.

Jenkins does not recommend that the hundreds of gospel texts that have been discovered be ushered into mainstream Christian belief and practice. According to the premise that the oldest Christian writings are more likely to be trustworthy than later Christian Midrash, he observes that the alternative gospels were written significantly later than the canonical gospels. He does suggest, however, that the rich diversity within Christianity includes the stories people wanted, stories whose interest and power have been meaningful to generations of Christians.

He notes that 21st-century values—such as women’s participation in sacred events—are supported more richly in extracanonical literature than in scripture. (However, I notice that this book’s cover illustration of the Anastasis, a 14th-century fresco at Istanbul’s Church of the Savior in Chora, is cropped at Eve’s arm as Christ is depicted pulling Adam and Eve out of their graves on the day of resurrection.) Moreover, theological questions investigated by medieval authors and readers—such as how one can reconcile God’s justice with God’s love and mercy—also contribute to the present interest in extracanonical treatises.

Jenkins demonstrates the long continuity of theological perspectives displayed in the lost gospels. However, the historical moment and intellectual environment of the writers can also reveal the historically specific and perhaps contested values of the authors and readers.

For example, the Infancy Gospel of Thomas recounts incidents in which the child Jesus, by his word alone, kills a child who struck him and children who refused to obey him. When parents and other villagers complain about his actions, Jesus blinds them. Jenkins comments sardonically, “When he is not killing people, the child Jesus is playful and carefree.” Clearly, the author of this infancy gospel was more eager to establish Jesus’ power than to present Jesus as a lovable child.

Why? I speculate that the author of the Gospel of Thomas responded to a social consensus that pictured the child Jesus as the medieval equivalent of the weak and helpless baby Jesus of the Christmas crèche. The author may have considered it imperative to insist, above all, on the intransigent power of the child God.

According to Jenkins, it was the 16th-century reformations, themselves representing a diversity of beliefs and practices, that effectively prohibited devotional use of extracanonical gospels. Luther’s sola scriptura mandated precision in what constituted scripture. The invention and use of the printing press also contributed to the critical examination of religious texts that led to rejection of the extracanonical gospels. Printing demanded standardization of the approved scriptures. Luther wrote that the invention of the printing press was “God’s highest and extremist act of grace.” Jenkins observes that claiming the absolute authority of scripture created “a massive loss of diversity in Protestant devotion.”

Although both grassroots and clerical iconoclasm were practiced in most branches of the 16th-century reformations, Jenkins exaggerates the consensus among reformers on the evil of images. Luther himself, in his treatise Against the Heavenly Prophets in the Matter of Images and Sacraments, stated that images of holy stories, such as those included in the German Bible (1534), should be painted on the walls of homes and churches “for the sake of remembrance and better understanding.”

The importance of The Many Faces of Christ is its support for the present diversity of belief and practice within Christianity. Jenkins concludes that “at no point in Christian history have believers been united into one single united church.” The historical evidence he brings to document this claim demonstrates that the repetitious call for Christian unity was not only prompted by dramatic diversity but has had unintended—and what we might call, without exaggeration, unchristian—consequences: the persecution of Christians, usually called heretics, whose beliefs and devotions differed from those of mainstream institutional Christianity.