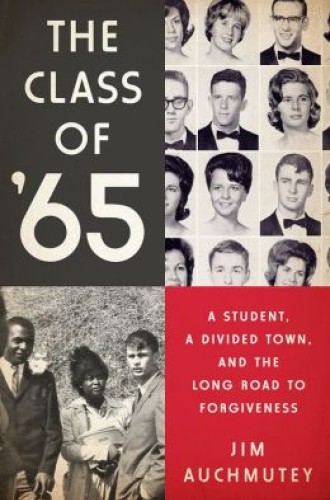

Made in Americus

Getting through school can be a harrowing experience in any era. Imagine the challenges for a certain handful of children 60 years ago in Americus, Georgia. The local school board wasn’t sure whether to admit these children, even though desegregation had been ordered by the U.S. Supreme Court. They were pelted with rocks and insults, made to fear for their safety even in their own homes. Curiously, these students were white—from the racially mixed Koinonia Farm.

Progressive Christians who didn’t live at Koinonia celebrated its brave stands. They admired how members held the farm in common, ate and prayed together, and tried to live out a model of the early church. Reinhold Niebuhr and Eleanor Roosevelt wrote about it. Clarence Jordan, its cofounder, would become known for the Cotton Patch Gospels, a colloquial version of the New Testament. Members Millard and Linda Fuller would establish Habitat for Humanity. Koinonia also impressed a nearby peanut farmer, Jimmy Carter, who was shrewd enough not to get too involved.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

But life at Koinonia left emotional scars on the children. Their parents, with the best intentions, had put them on the front lines. Local whites, unable to tell Christian communal life from Soviet communism and unwilling to countenance blacks and whites living together, tried to starve members out by refusing to trade with them. Several times Koinonia was bombed, its orchard was cut down, gunfire shattered windows. The children weren’t sure whether to be angry at the townspeople or at their idealistic parents—or even if they were permitted to be angry at all.

Jim Auchmutey focuses on Greg Wittkamper, a gangly boy who came of age at Koinonia as the civil rights campaign heated up. He embraced a prophetic role, accompanying the first black students at Americus High. His only companions during high school were African Americans who lived on the other side of the tracks. Daily run-ins with other white kids tested his commitment to nonviolence. They pushed him down stairs, pissed in his locker, struck him in the face—and still, with a mixture of Christian faith and adolescent drama, he literally turned the other cheek. He stood firm even though the entire school treated him as a pariah. Americus had become “the next Selma,” a battleground in the struggle for voting rights, and Greg took part in marches and sit-ins as long as he lived there. But upon graduation, he couldn’t wait to leave Americus far behind.

After the 40th reunion of the Americus High School class of 1965, some of his classmates reached out to Greg with poignant letters of apology. The Class of ’65 opens and closes with him at the mailbox, overcome by the letters.

“All I can do now is say that I am sorry, acknowledge the good principles behind Koinonia’s existence, and commend you for your courage,” wrote one. “You were right! I hope God has smiled on you for holding fast and suffering in His Name.” Another compared herself to Germans complicit in the Holocaust. Several, certainly not all, of his classmates had similarly repented and asked his forgiveness. Deeply moved, Greg sought out his onetime black acquaintances to learn what had changed for them—and what had not.

Too often the Jim Crow era has been mediated to audiences through the sensibilities of white people, with enlightened white persons in heroic roles. This could have been such a book. Shrewdly, Auchmutey has structured it so Greg’s story prepares us for the even more wrenching stories of black children.

We meet Robertiena Freeman, whose father, Robert L. Freeman, worked as the pastor of a sizable church and as a teacher and administrator at the middle school for blacks. He knew what the civil rights struggle might cost his family. Shots had been fired at his home and the letters “KKK” painted on the driveway. Nevertheless, Robertiena was committed to the struggle. “Daddy, I want to go integrate that school,” she said enthusiastically. “I’d like to go over there and make some white friends.”

There would be no white friends. Robertiena had already been tested—she had spent 30 days in jail for demonstrating—but still she was shocked and humiliated when police followed her on a date and arrested her for “fornication.” By then she was the only black student remaining of the four who had integrated Americus High. Her parents brought textbooks to the jail so she could study for final exams.

I wish Auchmutey had written more about the Freemans. Perhaps the most affecting moments in the book are about Robertiena in adulthood. She received no letters of apology from classmates, not even an invitation to the reunions. But oddly enough, her younger sister became principal of Americus High and invited Robertiena to come back and see it. By then, thanks to white flight, it was entirely black.

A longtime observer of Koinonia who spent almost 30 years at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution as a reporter and editor, Auchmutey knows the territory well. Much of his story has the power to shock, but his telling is more powerful because he is unshockable. Over the last decade he has talked to many participants in Koinonia and has imbibed the spirit of Clarence Jordan, whose large personality hangs over the town to this day.

This is Auchmutey’s first book, and he often telegraphs the plot as if he doesn’t trust us to keep reading this absorbing and timely story.

In 1965, the year Greg Wittkamper graduated from Americus High, the country had to reckon with how little progress had been made in race relations fully a hundred years after the Civil War. And now, 50 years after the Voting Rights Act, Americus remains deeply segregated, as does much of America. This heartbreaking book confirms that we all have far to go and much to forgive.