Texas tough

Outside the large First Baptist Church in the small West Texas town where I grew up, a handful of men gathered every Sunday morning to smoke one last cigarette before going in to worship. They were ranchers and farmers mostly, and their conversation consisted of three things: how dry it was, the prospects of the high school football team, and how dry it was.

Before going inside, one of them loved to repeat an old Texas saying: “It’s 250 miles to the nearest post office, 100 miles to wood, 20 miles to water, six inches to hell.”

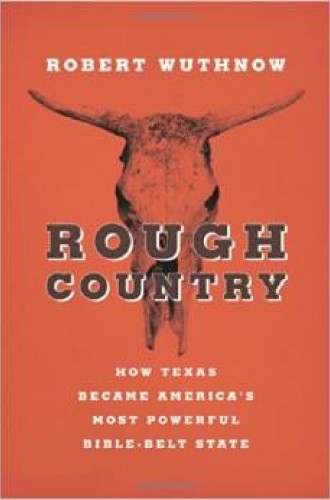

Sociologist Robert Wuthnow seeks to show how living in such an unforgiving and challenging land has shaped the perspective of its people and especially its religion. This rough country has been observed and experienced and often written about in letters and diaries by the settlers of the Texas frontier; in it, Wuthnow says, “nearly everything is rough: the land is rough, earning a living is rough, the people are rough, even the preachers are rough.” He goes on, “What to make of this roughness, and how to overcome it, are the most basic questions of everyday life.”