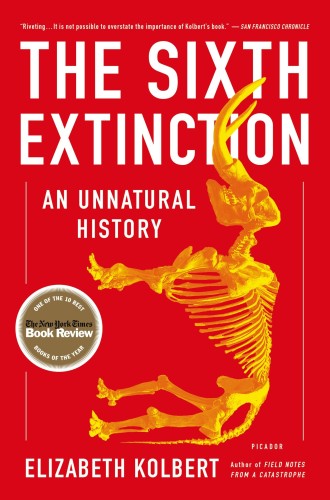

The Sixth Extinction, by Elizabeth Kolbert

“We broke this world. We did this,” declares Noah, played by Russell Crowe in Darren Aronofsky’s recent film. The title character discerns that the God-ordained purpose of his family is to liberate plants and animals from the horrors of human beings. “Our family has been chosen for a great task,” he says to his son Shem. “We’ve been chosen to save the innocent, . . . the animals.” And in the film, for Noah, the salvation of the world involves the annihilation of the human beings: Noah’s children are three boys; the human species will come to end. Noah tells his family as the rain begins, “If we were to inherit the world again, it would only be to destroy it once more.” To his youngest son he says, “You, Japheth, will be the last man. . . . The creation will be left alone, safe and beautiful.”

In the film, Noah hears about this apocalypse from God, but we can read about it in Elizabeth Kolbert’s The Sixth Extinction. To demonstrate how Homo sapiens has made a wreckage of the earth and sky, Kolbert introduces us to a chorus of scientists who show us evidence of the earth’s convulsions everywhere, from coral reefs near Australia to the population of bats in upstate New York. Her book is full of notes on the end of the world—at least the end of the world for human beings. The earth has survived mass extinctions before, and the earth will endure without us.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Kolbert contends that human beings have inaugurated the sixth in a series of planetary extinction events, the first being the global freezing phenomenon that marked the end of the Ordovician period 450 million years ago, and the most recent being the asteroid that ended the Cretaceous period 65 million years ago. The sixth extinction, she says, will end what the chemist Paul Crutzen has called “the Anthropocene,” this “human-dominated, geological epoch” during which human settlements have altered more than half of the earth’s surface and anthropogenic emissions have modified the atmosphere.

“Owing to a combination of fossil fuel combustion and deforestation,” Kolbert explains, “the concentration of carbon dioxide in the air has risen by forty percent over the last two centuries, while the concentration of methane, an even more potent greenhouse gas, has more than doubled.” Human beings have restructured the planet in a short amount of time in terms of the evolutionary clock. The rate of change matters because flora and fauna need time to adapt in order to survive. Kolbert draws an analogy with alcohol consumption: “Just as it makes a big difference to your blood chemistry whether you take a month to go through a six-pack or an hour, it makes a big difference . . . whether carbon dioxide is added over the course of a million years or a hundred.”

Of course, not all plants and animals are suffering in the Anthropocene. As human beings continue to recompose the earth, “some species will thrive,” Kolbert observes. The earth will go on, even after we succeed in suffocating our own species with toxic air. Kolbert’s realism is striking, especially as we hear experts and activists plead for an abrupt halt to ecological destruction to save the world from catastrophe. For Kolbert, the catastrophe has already begun, and there’s no undoing it.

Kolbert insists that “man was a killer . . . pretty much from the start.” There’s no room for romantic notions of peaceable human coexistence with the rest of nature. The emergence of human life has been a protracted extinction event. “Our restlessness, our creativity,” Kolbert writes, our insatiable desire to stretch “beyond the limits of [our] world” are part of the human condition. We overreach, we take what we don’t need, we are slaves to habits of greedy consumption. Call it our original sin: a constitutive dissatisfaction that compels us to gobble up what we shouldn’t, to devour what we needn’t—forbidden fruit. “This capacity predates modernity,” she notices, “though, of course, modernity is its fullest expression.”

The Sixth Extinction exposes the irony of the name Homo sapiens. We named ourselves wise and knowledgeable—sapere, a Latin word meaning “to know” or “to discern,” a word that has everything to do with exercising wisdom and making sensible decisions. Yet here we are, panicked because we’ve created the conditions of our own extinction. Kolbert quotes the ecologist Paul Ehrlich to this effect: “In pushing other species to extinction, humanity is busy sawing off the limb on which it perches.” The human story, according to Kolbert, reads like an ancient Greek tragedy. In the penultimate scene of the play, we finally figure out that we were the ones who set in motion the processes of our own death, and it cannot be undone. All that’s left is to determine which other species we’ll be taking down into the soil with us, where together our fossilized remains will mark yet another apocalyptic end to an epoch.

We will leave a living legacy as well. On page after page, Kolbert documents people who have given themselves to sustaining other forms of life—from conservationists in Panama who work to preserve the habitats of endangered frogs, to biologists in Brazil who are trying to protect plots of megadiversity in the state of Amazonas. She tells a story of an animal reproductive physiologist who tries repeatedly and without success to artificially inseminate a Sumatran rhino named Suci at the Cincinnati Zoo. It is an attempt to continue the 20 million year lineage of a rhino species, a creature E. O. Wilson has called a “living fossil.” And there’s the doctor at the San Diego Zoo whose work involves stimulating the gonads of a Hawaiian crow named Kinohi—one of only a hundred left in the world, all in captivity. Three times a week, the doctor strokes the sexual organ of the bird in order to produce ejaculate that is rushed to a zoo on Maui for an insemination procedure on a female Hawaiian crow. This “tragicomic sex provides more evidence—if any more was needed—of how seriously humans take extinction,” Kolbert comments. “Such is the pain the loss of a single species causes that we’re willing to perform ultrasounds on rhinos and handjobs on crows.”

Millions of years after our extinction, perhaps a species of sentient beings will emerge from the postapocalyptic milieu and discover these stories and know that at least some of us loved and cared for our neighbors, even our nonhuman ones.