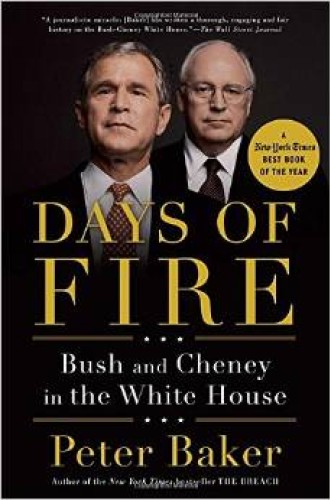

Days of Fire, by Peter Baker

Presidential history is a venerable and popular art. Vice presidential history, not so much. One of Franklin Roosevelt’s vice presidents, John Nance Garner, famously complained that the office is “not worth a bucket of warm piss,” and few historians—or vice presidents—have contested the metaphor.

It is therefore symptomatic of the exceptional character of the vice presidency of Dick Cheney that little surprise is occasioned by Peter Baker’s treatment of Cheney as a costar with President George W. Bush in this entertaining if superficial first draft of the history of Bush’s years in the Oval Office. Few Americans today could identify any of FDR’s vice presidents. And when was the last time you heard the current administration referred to as the Obama-Biden White House? Yet most of us regard the phrase “Bush-Cheney regime” as apt. Even those, such as me, who hold Cheney in very low esteem would not deny his powerful influence on the politics and public policy of the early years of the new century.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The Cheney vice presidency raises a number of crucial questions: Just how powerful was he? How did he secure his power? How did he exercise it? Why did he use it for the ends he did? Baker addresses these questions by way of a highly detailed, sometimes day-by-day narrative in which he attempts to create “a neutral history” of the Bush years. But by pursuing a strictly narrative approach, Baker fails to provide much of an answer to these questions, which require analysis and not simply a story. And by eschewing judgment on the persuasiveness of competing claims about what happened and why, thereby confusing neutrality with objectivity, Baker leaves his readers with the impression that answers to these questions are more elusive than they are.

Unfortunately for Baker, he has a hard act to follow: Barton Gellman’s Angler: The Cheney Vice Presidency (2008). Gellman is keenly analytical and unafraid to sort through the evidence and make persuasive arguments about where the truth probably lies. Baker mentions Gellman’s book once in passing in his text and cites it a few times in his notes, but he never directly engages Gellman’s arguments or evidence about issues such as Cheney’s selection as Bush’s running mate, his control of the presidential transition in late 2000, his actions on 9/11, his influence on economic and environmental policy, and his preeminent responsibility for administration policy on terrorist surveillance, imprisonment, and interrogation.

Cheney and other government policy makers often use a metaphor for the kind of reporting and analysis Gellman has done: “deep diving.” Gellman analyzes the differences between interviewees’ claims and the documentary evidence, usually coming down on the side of the documents. Baker, by comparison, swims along the surface: he simply points out the differences and, in effect, declares a tie, leaving important questions undecided and by implication undecidable.

Baker sets out to dispel the claim that Bush was merely—as in a James McMurtry song—Cheney’s toy. “Bush,” he says, “was hardly the pawn nor Cheney the puppeteer that critics imagined.” But Baker’s mixed metaphor is inapt. It fails—as does his argument for Bush’s autonomy—to appreciate the genius of Dick Cheney. Pawns and puppets are not human beings; they have neither reason nor will of their own, and hence are much easier to manipulate. Cheney did not, for the most part, make decisions that Bush should have made (though occasionally, and in some very important instances, he did). Bush, as the president himself insisted, was the ultimate decider. What Cheney did do, brilliantly, was determine to an extraordinary degree the context of advice, information, and argument within which Bush made his decisions. Bush may not have been Cheney’s toy, but Cheney toyed with him with remarkable skill.

Cheney took full advantage of his standing as the one White House adviser who could not be fired, and he played on his rare position as a vice president without his own presidential ambitions. He injected himself into policy-making councils and committees where no vice president had ever ventured and created a few new committees for himself. He imbricated his office within the structure of presidential decision making in unprecedented ways. For example, Cheney’s top aide, Lewis “Scooter” Libby, was not only his own chief of staff but also an assistant to the president, with standing and access equal to that of Bush’s top advisers. Cheney used his control of the presidential transition to plant his allies in the State, Defense, and Treasury departments. He used proxies throughout the government bureaucracy to pursue his aims without leaving telltale fingerprints. He also controlled the flow of information and kept potential adversaries under careful surveillance. For example, e-mails from staff on Condoleezza Rice’s National Security Council were blind-copied to Cheney’s office without the correspondents’ knowledge.

Cheney sized up his president with typical acuity. Bush was not dumb, but he was incurious, uninterested in detail, impatient with extended debate, and delighted to have others do his homework for him. Cheney exploited these traits, which were the opposite of his own. He was himself intensely curious, and he was well informed—even learned—about the arcana of economics and constitutional law. Away from his desk, he lugged around a huge briefcase filled with thick briefing books, which he read carefully, right down to the appendices and footnotes. He was a talented listener, patient in hearing out interlocutors before advancing penetrating questions that got to the heart of the matter. He played his cards close to the vest, saying little or nothing in collective meetings with the president, then remained afterward to offer his counsel privately when there was no one to contest him. Alternatively he waited for his weekly breakfast with the president to advance his projects.

To what ends did Cheney deploy his remarkable abilities as a bureaucratic in-fighter? What best explains why he sought the power he accumulated and the policies he pursued with it? Here again, Baker is not much of a guide. He leaves it largely up to his readers to figure things out for themselves.

Cheney had two lodestars for much of what he did in the Bush White House. First, he was fanatically devoted to a radical view of presidential power that some observers went so far as to call monarchical. Second, when confronted with the possibility of disasters of low probability but high consequence, he had a propensity to err on the side of exceptional caution and to do whatever was necessary, niceties of law and ethics aside, to reduce their probability to as close to zero as he could. The war on terror was ready-made for the conjunction of these two qualities: it afforded plenty of unlikely but awful consequences that called for the president to exercise exceptional constitutional latitude. All of the appalling landmarks of the first Bush administration were a consequence of this conjunction: the imprisonment of suspected terrorists without trial at Guantánamo, the use of torture, warrantless domestic surveillance by the National Security Agency, and, not least, the war in Iraq.

By Bush’s second term, blowback from Cheney’s strenuous efforts had begun to wear away his power. Some of those over whom Cheney had ridden roughshod in the first term, as well as some newcomers, were emboldened to push back. Of particular importance, Baker implies, was Rice, the one adviser who could compete with Cheney for the ear of the man whom she inadvertently referred to as “my husband.” Cheney remained a force to be reckoned with, but Rice and others helped Bush leave office with a national security policy that evolved from appalling to just plain awful. As Baker writes, the principal accomplishment of Bush’s second term was mitigating the damage of his first term.

Baker says little about Bush’s domestic policies, from the tax cut that wiped out the Clinton budget surplus to the education reforms that ensured that the tail of testing would wag the dog of learning in American schools. Baker does discuss the financial meltdown of the closing months of the Bush regime, but he says nothing about the role that the administration played in fostering it. This is perhaps as it should be in a book in which Cheney has equal billing. Though the vice president did have some impact on domestic policy, what Cheney cared about most deeply, as he often said frankly, was protecting his country from dire threats from abroad, however improbable, and securing for the executive exceptional power to address such awful scenarios while insulated from the constraints of Congress, the courts, and public opinion.

Although Bush and Cheney were unpopular by the time they left office, they were both confident that they had acted in the national interest and were, they both said, willing to leave their reputations to history. Unfortunately, new regulations that Cheney forged will make it difficult for historians to get their hands on the documents they need to make that assessment anytime soon.