Miniseries midrash

I often tell students the hardest review to write is the B- review. Exemplary books or movies are fun to praise and miserable ones are fun to condemn. Stories that are only so-so are harder to evaluate. This is true even when a story is not culture-war radioactive, championed by Glenn Beck, lampooned by Stephen Colbert and touted by churches and Christian bookstores. The History Channel’s five-part miniseries The Bible is not excellent or miserable. It’s so-so.

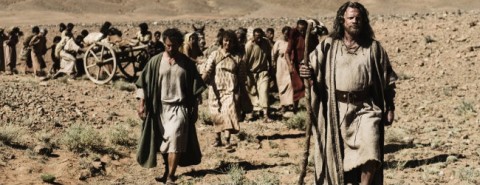

The word epic is used liberally by the show’s promoters. Its ten-hour length seems a compromise between the Bible’s grand scope and the short attention span of TV watchers. The Bible is the latest attempt to recapture the lightning in the bottle of Mel Gibson’s nine-figure-grossing The Passion of the Christ. Producers Roma Downey (who plays the elder Mary) and Mark Burnett (a former reality-TV producer) seem nostalgic for the days of Cecil B. DeMille. They provide state-of-the-art special effects, English-accented actors, and countless swordplay scenes shot with effects that rival those of Gladiator. Who cares? We’ve seen swords and sandals before. It also features, as you may have heard, a rather striking Obama look-alike as the devil. Producers assert that he is a prominent Moroccan actor (Mohamen Mehdi Ouazanni), and news reports say the producers gave money to Obama’s campaign in 2008. That’ll probably be the show’s lasting impact, for better or worse.

The story differs significantly from Gibson’s Passion in scope and ambition. And unlike Gibson’s movie, this project had biblical scholars and observant Jews as advisers (including one Joel Osteen, ensuring that the prosperity gospel would not be misrepresented). Even St. Stephen’s unredeemably anti-Jewish speech in Acts is scrubbed clean of anti-Judaism.