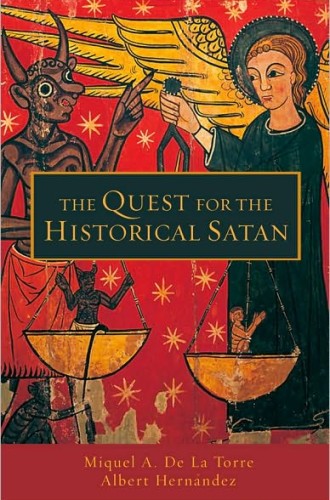

The Quest for the Historical Satan, by Miguel A. De La Torre and Albert Hernández

According to Albert Schweitzer, the quest for the historical Jesus ends with the questers looking down a well and seeing their own reflections. Could the same be said of a search for the historical Satan? With few exceptions, we have tended to see Satan in the face of the other. Satan has proved to be a useful foil to describe one’s enemies and to make sense of the continuing presence of evil and suffering in the world, whether or not one believes in a literal Satan.

A quest for the historical Satan has been undertaken for the purpose of understanding how this image came to be, how it has been used in history and how, despite technological progress, it is still used to explain the fact that evil remains with us. Leading this quest are two professors from Iliff School of Theology, ethicist Miguel De La Torre and historian Albert Hernández. They begin in the present, introducing us to the ways in which Satan is portrayed by Hollywood and by various religious communities. From there, they go back to Egyptian mythology and move through early Jewish developments and on to evolving Christian and Muslim understandings.

Satan began as a trickster with an ambiguous identity and became the embodiment of absolute evil. The evolution of this image is fascinating and enlightening, and as we delve into it, we discover that many of our assumptions about Satan and evil are misguided and mistaken.