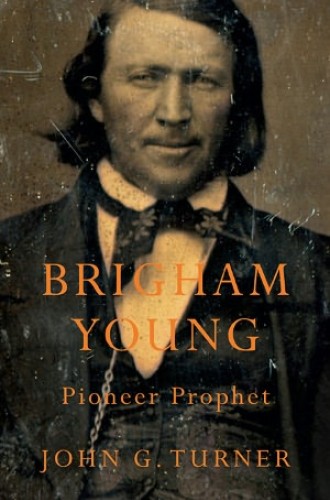

Brigham Young, by John G. Turner

Brigham Young, unlike Joseph Smith, played no role in the translation of the Book of Mormon. He never ran for president of the United States, as Smith did in 1844. And Young was not dramatically martyred, as Smith was when a mob shot him in his prison cell. But without Young, we might not remember Smith. Without Young, Mitt Romney’s Mormonism might not exist to be an issue for some voters in the current presidential election.

Although best known today for the university that bears his name, this rough-and-tumble 19th-century man was one of the most pivotal figures of his century. As the primary leader of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints after Smith’s assassination in 1844, Young saw thousands of followers across the frontier, helped establish the Mormon community in Utah and throughout the West and challenged the federal government at just about every level. Now, thanks to historian John Turner, we have a comprehensive biography of Young and his times.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Several years ago, Turner wrote a biography of Bill Bright, the 20th-century founder of Campus Crusade for Christ. With Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet, Turner turns to another century. It is an exceptional work. In the space it would take Robert Caro to narrate two years of Lyndon Johnson’s life, Turner carries Young from a Vermont cradle in 1801 to a Utah grave in 1877. He traces Young’s frustrations with the Protestant churches around him in upstate New York and tells how he turned to Joseph Smith’s new church in 1832. Then Turner examines Young’s ascension to power after Smith’s assassination, his decision to lead the fragile church to the frontier West and his building of the kingdom in the Great Salt Basin.

From the 1850s to the 1870s, Young was consistently at odds with the federal government. Sometimes the issue was plural marriage, which the new Republican Party declared, with slavery, was a “twin relic of barbarism.” Other times, the conflicts were over federal jurisdiction or non-Mormon immigrants and their economic pursuits. Through tribulations and trials, both metaphorical and literal, Young not only survived but thrived. Under his direction, Mormonism established a permanent home in Utah. It had tens of thousands of members and grew significantly throughout the 20th century.

In spite of this success, Young was pestered for 20 years as the leader of the LDS Church. National attention and infamy began in earnest in 1857. In September that year, a group of Mormons slaughtered the men, women and most of the children in a wagon train heading from Arkansas to California. Scholars have vigorously debated Young’s involvement. What is clear is that he did little to bring any of the criminals to justice. It was not until the 1870s that anyone was tried. John D. Lee, Young’s “adopted son,” who was convicted and executed, believed himself to be a scapegoat.

After the Civil War, Mormons were under political siege by the federal government and by new immigrants. Congress, presidents and the Supreme Court attacked polygamy, while new railroads brought non-Mormon immigrants into Utah and troubled Mormon economic communalism. By the time the embattled and tired Young died, the church was soundly established, but it was still under attack.

We can learn a lot about the development of Mormon theology from Turner’s book, far more than can be gleaned from previous biographies of Young. He was part of the movement of Mormonism away from traditional Protestantism as Mormons embraced sacred texts other than the Bible, such as the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price, baptized people who were already dead, including George Washington, and thought of God in human forms, with a body and a wife or wives.

Turner is at his best when he is placing the elements of Young’s life within the main contours of broader 19th-century America. For instance, Young had visions of angels, spoke in tongues and believed that some healing amulets could work. At the same time, he was a savvy businessman who owned and operated mills and shops. His spiritual and material experiences were not uncommon. Abolitionist Sojourner Truth claimed to hear God. Dwight Moody was a former shoe salesman and an expert marketer.

Or take Young’s approach to marriage. He did not seem thrilled when Smith instructed him in 1842 to “go and get another wife,” but he followed his religious mentor. Over the course of his life, Young had “celestial marriages” with more than 50 wives. These were quite distinct from regular marital bonds. Many of the wives never lived in the same home with Young, many probably never had sex with him, and more than a dozen received a portion of his estate when he died. These marriages were more theological than carnal (although sexual appeal was part of it as well). Mormon theology developed in a way that privileged families over individuals. Through marital bonding and even spiritual adoption, members of the church linked themselves in the realms after this life was done.

Polygamy disgusted most white Protestants, and they dismissed Mormon appeals to the biblical examples of Abraham, David and others who had multiple wives and sexual partners. Of course, put into its 19th-century context, Mormon polygamy appears far more humane and equitable than some other forms of sex and marriage. In the South enslaved black women could be used as sexual concubines, even purchased as “fancies” by rich slaveholders. They were unable to choose whom they married, and they certainly did not receive estate shares.

As pivotal as Young is to the history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, he has also been a thorn in the side of many contemporary Mormons. Like the apostle Paul, Young wrote and said a number of things that make us squirm now. In the 1850s he preached that if any white man had sex with a woman of color, “the only way he Could . . . have salvation would be to Come forward & have his head Cut off & spill his Blood upon the ground.” Turner downplays this kind of white supremacy by claiming that Young was similar to other whites of the era who disdained African Americans and particularly interracial sexuality. By focusing on what Young had in common with other whites, however, Turner misses an opportunity to show particular theological dynamics of Mormonism. The church’s obsession with physical bodies and family lineage led Young and others to have a particular brand of white supremacy—one that left the church willing to give up polygamy in 1890, while continuing to bar African Americans from the priesthood until 1978.

At other times Turner seems too defensive of Young. One prime example is related to political bribery. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, the LDS Church bribed a series of politicians to help with lawsuits over polygamy. Turner writes that Mormons “were hardly the only Americans with a less than saintly record when it came to political ethics.” His example of other political bribery is the Crédit Mobilier scandal, in which the Union Pacific Railroad Company made a bundle through inflated construction contracts. But there is a significant difference between the Union Pacific and the LDS Church. One claimed to be a church.

My quibbles with Turner’s marvelous book come from a place of profound admiration for it. Those who want to know more about Mormonism’s birth and growth will want to get a copy. It’s dense, but for good reason. There was as much written in the 19th century by and about Young as there was about Abraham Lincoln. Turner’s effort is worth it. He teaches us not just about Brigham Young but also about American society during Young’s lifetime.