Apocalyptic visions

Discussion of Gnosticism at a recent gathering of local clergy generated a comment from one pastor that perhaps Christian scriptures should be kept in a loose-leaf binder so we can add and remove documents at will. How unfortunate that our Bibles come on gilt-edged paper securely bound between leather covers. Truth should not be so defined and confined!

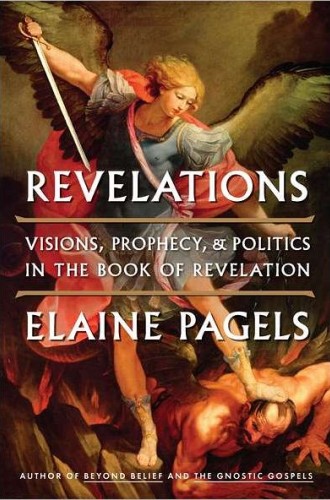

Elaine Pagels’s Revelations could be a resource for a project to remove canonical boundaries. This readable and tendentious book repeats a formula that has become a winner in an era of spiritual self-empowerment: highlight parts of the canonical New Testament or early church orthodoxy that are most likely to ruffle modern progressive feathers and contrast those with selections of Gnostic writings that are most likely to resonate with contemporary preferences. In this contest early church leaders and canonical scriptures come across as patriarchal, authoritarian and vindictive in contrast to the alleged inclusivity, generosity and feminism of Gnosticism.

The astonishing cache of ancient writings discovered at Nag Hammadi in Upper Egypt in 1945 provides most of the Gnostic texts Pagels cites. These spiritual books display the diversity of theologies and spiritual writings that swirled around the Mediterranean world in the early centuries of the Common Era. Loose-leaf binders had not yet been invented, but they are in effect what the church had; the canon of authoritative Christian documents had not yet stabilized. Churches scattered across and beyond the Roman Empire had not yet formed consensus on how to express central doctrines such as the Trinity. Who or what would serve as theological authority for doctrinal discernment? Only apostolic eyewitnesses to the Christ event? Could there be later revelations?