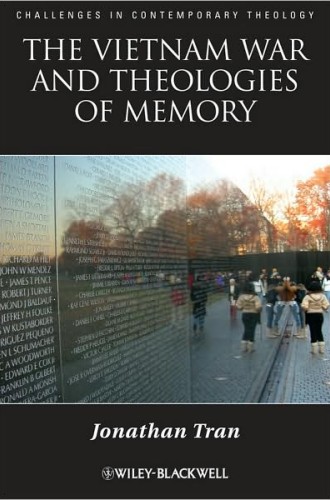

A Review of The Vietnam War and Theologies of Memory

Why are wars so common given that they are so destructive? When they are so rarely won? When they are so often fought for reasons that turn out to be lies? When they invariably bring out the worst in human brutality? How do individuals and societies recover from such destruction and mendacity?

Theological contributions to the enormous literature on such questions have been few and far between. Great theology books have been written about peace, but aside from studies of Old Testament warfare, hardly any have been written on war. The Vietnam War and Theologies of Memory is thus a welcome contribution to theological ethics.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The lack of theological analysis of the Vietnam War is particularly important for Jonathan Tran, a Vietnamese American teaching at Baylor University. "How could something as theoretically remote and morally pristine as theology relate to something as politically important as America's killing in Vietnam?" he asks, and the book is an answer to that question. One of numerous recent attempts to challenge the influence of Reinhold Niebuhr, Tran's book may eventually take its place alongside works like William Cavanaugh's Torture and Eucharist and J. Kameron Carter's Race: A Theological Account. In the wake of giants such as Stanley Hauerwas, Rowan Williams and John Milbank, Tran is bold enough to recognize the radical politics of patristic and medieval theology and to claim that such theology is of direct relevance to contemporary political theory.

Tran begins by focusing on the domino theory and boredom (or, as Tran sometimes puts it, fast time and slow time), both of them disfigurements of time that manifest the fear of time. Proponents of the domino theory feared that time was running out before history would spin out of control and all of Southeast Asia would fall to the communists. Just as the assumption that resources are scarce begins every economics textbook, so, Tran argues, the assumption that time is running out undergirds war. For the Americans in Vietnam, the domino theory trumped all other strategic and pragmatic considerations in U.S. foreign policy.

The second disfigurement of time was in the lives of the soldiers. According to Vietnam veteran Tim O'Brien, war was

a strange kind of boredom. It was a boredom with a twist. . . . The day would be calm and hot and utterly vacant, and you'd feel the boredom dripping inside you like a leaky faucet, except it wasn't water, it was a sort of acid. . . . Then you'd hear gunfire behind you and your nuts would fly up into your throat and you'd be squealing pig squeals. That kind of boredom.

Such boredom creates a desperate need for action. But action quickly becomes atrocity when, for example, the bored soldier expects to be finally in a firefight but encounters peasant farmers instead of enemy soldiers.

In the face of such fearful distortions of time, Tran turns to Balthasar, Aquinas, Heidegger, Barth and Augustine in order to develop a theological account of time that might make war unimaginable. Tran's detailed discussion of Heidegger and Barth, for example, shows how time is distorted by our fear of death (Heidegger), which in turn encourages us to forget or misunderstand time's relationship to eternity (Barth). "To view time shorn of eternity," Tran contends, is "to grasp creation as if there were no Creator." Time is not an enemy to be feared; like all creation it is "sustained at all times by the eternal God who makes his fellowship with time." If friendship is the way Christians relate to other humans, patience is the way to relate to God's creature, time. If temporal desperation leads to violence, an adequate theological account of time will lead to patience, which Tran helps us to understand as friendship with time.

Throughout the book, Tran returns to the story of the prodigal son. Like the Americans in Vietnam, the prodigal displayed a temporal desperation, first in his inability to wait for his inheritance and second in his "wild living." What saves the prodigal is memory—"How many of my father's hired hands have bread enough to spare?" Hence, in part three Tran turns to the question of whether and how Christians might remember horrors like the Vietnam War. This part might be described as an argument for the church as the site of a radically democratic politics "generous enough for memory," where memory means "a practice of hospitality that makes space for the past."

This past remains present in the veteran, in those who "surrendered him to the state and its killing," in the poetry of abandoned Amerasian children, in the Veterans' hospitals and in numerous other ghosts that we, like Sethe in Toni Morrison's Beloved, remain haunted by. But instead of receiving the past embodied in these strangers and enemies, we devise elaborate strategies of avoidance—silencing, repressing, romanticizing, forgetting. Tran is most concerned with two such strategies—forgetting, as advocated by theologian Miroslav Volf, and the reintegration practices of warring societies.

Volf argues that memories of some events are too painful to be redeemed. Instead the events will be forgotten. After final justice has been served, such memories will slip the minds of those who are rapt in eternal worship. Tran argues instead for "a type of recapitulation, where human history, and its manifold memories, is drawn into God's life of love, which need not forget." For Tran, following philosopher Paul Ricoeur, our memories are redeemed by being renarrated. (Volf too knows the power of renarration, but for him the most painful, horrible things remain outside its scope—voiceless facts that admit of no retelling.)

Tran's complex and intricate argument may be summarized with these lines: "What will occur at the Judgment is not a weighing of all considerations, the view from everywhere of everything, but a reckoning of creation in the now-reigning terms of the Lamb." For both Tran and Volf, truth is narrated from particular places. Our memories are not facts, they are stories, and highly contested stories, susceptible to multiple narrations. The kind of renarration Tran has in mind is the kind that happens at the end of a mystery novel when Poirot or Miss Marple retells the story we have just read. Such renarration is also what happens, or begins to happen, in the act of forgiveness.

The renarration of forgiveness occurs in the way the forgiver says, "You are better than your actions," thereby opening a space for restored selfhood. But forgiveness is not the only way to restore selfhood. Societies that deliberately and systematically turn their young into killers and then sacrifice them in the name of "freedom" need a means of reintegrating those persons back into society. For such purposes, modern societies have developed elaborate systems of justification; they narrate the soldier's violence as "more than, and hence morally less than, killing" by draping it in the language of patriotism, heroism and sacrifice.

Such narration is thoroughly liturgical; it is enacted in parades, medal ceremonies and monuments. The effect of such liturgy is to re-present the soldier's past, to society and to the soldier, as more than the past of a killer. "Those who do not kill but reap its benefits are responsible for seeing those who killed as something other than killers" (emphasis Tran's). Of course, this is what broke down in regard to the war in Vietnam. The returning soldiers were spat on and discriminated against. "Having killed even though they did not want to, the vets returned to a bizarre counter-liturgy where they incurred guilt instead of relinquishing it." The Vietnam Veteran's Memorial emerged as an attempt to make up for this abandonment of the veteran. But the price of coming to terms with the past is the domestication and depoliticizing of those memories. By channeling public memory into private reverie the memorial places the war squarely within the national mythos.

Such national liturgies of reintegration are relatively new. Before the nation-state emerged with its justifications of killing, there was the church and its practice of penance for killing. The predicament of the Vietnam veteran ought to be an occasion for the church to recall that it possesses its own liturgies that have the power to renarrate soldiers as more than killers—in this case to renarrate them as forgiven killers. Building on his account of Ricoeur and drawing on the work of former Vietnam chaplain William Mahedy, Morrison's Beloved and Lillian Smith's Killers of the Dream, Tran shows how communities can gather around victims and victimizers and help them retell their stories.

In the case of Mahedy and Smith, Tran's examples are explicitly tied to the Eucharist, that space where "killers become confessants, that is worshipers" and "begin to see in oneself the enemy and in the enemy one to be loved." But his boldest example is one that is "fleeced of the Eucharist's liturgical counter-formation"—the POW/MIA movement. There is little evidence that Vietnam continues to hold prisoners of war, yet the myth that it does exerts tremendous power. Many writers have attempted to account for that power. They often argue that the POW/MIA myth serves to justify the war by portraying the Vietnamese as sadistic and reversing the roles of victim and victimizer. Or they say that concern for the POW/MIA is a kind of penance for the way the American public abused the returning veterans. Without exactly denying any of those readings, Tran suggests instead that the POW/MIA myth endures as a home for the ghosts that cannot be exorcised. Its proponents are "perhaps the only group of Americans who do not want to forget the war." While the rest of the country wants to "just get over it," "these apparitional communities keep vigil, waiting for the returning dead."

Tran is at his best when analyzing the POW/MIA movement and other stories from the war and the lives of the veterans. His remarkable account of the position and suffering of the Vietnam veteran is among the most moving sections of the book. Moreover, it enacts textually the book's argument. That is, this section and others transform the book from a presentation of an argument into the embodiment of the argument. Only a Vietnamese American transformed by the church's liturgy, the study of theology and the politics of listening and traveling could learn to inhabit time in a way that so carefully tends to the stories of those who ravaged the land of his forebears.